Extra

Atmospheric Experiments

In which Joe visits unmarked historical sites.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- Paul Smith, "Chemins de fer atmosphériques", in In Situ,

no. 10 (2009), online:

première partie, and deuxième partie.

In this chapter I will review some experimental atmospheric railways. My focus is on the locations rather than on the inventions themselves. These demonstration railways have left nothing for us to see. But for some of us it may be of some spiritual value to stand on the ground where an event took place, and whether it is of importance to the many is not the main consideration to the few who stand there. I visited only two of them myself, to a large degree because I did not know where the others were before my travels.

1826-27 : John Vallance at Brighton.

An Englishman called John Vallance secured a patent in 1824 for a railway that would run inside a tube and be propelled by exhausting air in front of the car. Two years later, still a year before the Rainhill Trials, he built a demonstration of his invention on land he owned in Devonshire Place, Brighton. The wooden tube covered in canvas was eight feet in diameter and 120 feet in length, and he had an air-pump at each end in order to run a carriage back and forth at a gentle 2 miles per hour by atmospheric power. This was the very first atmospheric railway in the world. The cylindrical carriage, 22 feet by feet 6 inches, ran on rails inside the tube and had lateral wheels to steady it. Vallance allowed about an inch of space around it, which he said was intentional, to show that it still worked even with an imperfect effect.

With the entire car inside the tube, Vallance's invention was of the type later called a pneumatic railway, which was demonstrated quite a bit later by Thomas Webster Rammell at the Crystal Palace and Alfred Ely Beach under Broadway in New York. Inventors after Vallance supposed that people would not like to ride very far inside a dark tube, and so they tried to find ways to connect a standard train to a piston inside a tube. The four atmospheric railways were all of that type.

Sad to say, no images of Vallance's achievement survive, and the only good descriptions I know of are in an article in the Brighton Herald paper for September 16, 1826, and a few mentions in 1827 in The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette. The length is given as 120 feet in Hadfield and 150 feet in Smith, and the latter gives Vallance's address as 1 Devonshire Place. The street is only one block long, so it should not be too hard to find the spot.

By luck, we have available a map of Brighton dated 1822, not long before Vallance's landmark installation. Here is a detail showing the street where it was located. The map key calls Rectangle 14 St James's Chapel (thus, Chapel Street), but the other rectangle at Devonshire Place has no number.

No.1 Devonshire Place is at the corner, west side of the street, north side of St James's Street. The block on that side was already built up in 1822, so there would have been no room for an atmospheric railway in 1826. But on the east side there was open land, almost half the block, at the Edward Street end, more than 200 feet in length. This must be the place. All we need to assume is that Vallance owned both sides.

The photograph below shows what it looked like in 2018. Of some interest is that the ground is not level, a feature not mentioned in the available descriptions. The upper half of the street has a greater slope than the lower, which might suggest that the demonstration was closer to St James's Street, but with both sides of block already built up in 1822, it does not seem possible.

The upper end of Devonshire Place, Friday, June 29, 2018.

There is no blue plaque. It would read:

1759-1833

BUILT THE FIRST

ATMOSPHERIC RAILWAY

ON THESE GROUNDS

IN 1826

And passers-by would ask, "the first what?"

Vallance published in 1824 his pamphlet On Facility of Intercourse, with the aphorism under the title, "Though this be madness, yet there's method in it." It was included in his longer work of MDCCCXXV, On the Expedience of Sinking Capital in Railways, in which he questioned the future of "loco-motive" railways. He wrote:

To come up to the conditions, which must be fulfilled before we can be considered to have brought the art of intercourse to absolute perfection, the method by which it is effected must admit of unvarying certainty—the ability of travelling with the greatest rapidity we can exist under—the power of rendering this motion continuous and unremitting, from the commencement to the termination of the journey—and of transmission at the least possible expense.He raised the objection that the locomotive used more than half its power moving itself, and required strong track and bridges to support its own weight, while the rest of the train was much lighter. This was the argument for lineside power, but a method capable of more speed than the only time-tested method, cable railways. For those who feared the effects of air pressure, he calculated from winning times that race-horse jockeys travel as fast as 33½ miles per hour, without having trouble breathing, and added that with a head wind it may be that they travel as much as fifty miles per hour relative to the air around them.

The following comment on skeptics appears in quotes on the title-page verso, which I have traced to The History of America by by William Robertson, D.D., 1822.

They maintained, that if there were really any such countries as Columbus pretended, they could not have remained so long concealed ; nor would the wisdom and sagacity of former ages have left the glory of this invention to an obscure Genoese pilot.

Before we set out to Brighton in search of Devonshire Place, because it was Friday, we left London very early and made a detour to the Bermondsey Antiques Market to look around. After that pleasant diversion, we walked toward London Bridge station, stopping for a breakfast of baked goods and coffee at the very comfortable Fuckoffee cafe. Inside the toilet room door is posted a document from the authorities denying a trademark because the name is offensive. After a different round of legalities, the street side sign was changed to a more acceptable form with an asterisk in place of the "u". The railway journey from London Bridge followed the same route as the London and Croydon Railway as far as Norwood Junction, and then the route of the Croydon's one-time tenant the London and Brighton.

Below are a few other sights worth seeing— in case you hesitate to take a day out just to see a row of houses where a demonstration atmospheric railway was, two hundred years ago. May I admit I would also hesitate. The Toy and Model Museum will bring back memories, and Volk's electric railway is said to be the oldest such still in operation.

Brighton station, Friday, June 29, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

Brighton Toy and Model Museum, Friday, June 29, 2018 © Joseph Brennan.

Brighton Toy and Model Museum, Friday, June 29, 2018. © Helen Schreiner.

Volk's Electric Railway, Friday, June 29, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

Volk's Electric Railway, Friday, June 29, 2018. The third rail is just in from the right-side rail.© Joseph Brennan.

The far end of Volk's Electric is at the remote clothing-optional part of the beach. No pictures here. I observed no more than one naked fat guy pulling up his swim trunks. It was not exciting.

1836 : Henry Pinkus at Kensington, London.

Pinkus, an American living in London, says Hadfield, "seems to have laid some track (half a mile was proposed) fitted with 15 ft lengths of 13½ in tube, and set up a 30 hp steam engine and three air-pumps." This was on the banks of the Kensington Canal. However in the same year the owners of the canal arranged to sell it to a railway company, which removed Pinkus's track as soon as they gained possession. I don't know precisely where Pinkus's track was. It was probably in the vicinity of West Brompton station on the Overground.

After some more elaborate and impractical designs, Pinkus had settled on something very similar to what of Clegg and Samuda would soon propose. The main difference was on the most problematic part, the linear valve. Pinkus proposed curved "lips" of flexible metal that would spread as the piston arm passed through but otherwise spring back tightly against each other.

1838 : Samuel Clegg at Chaillot, Paris.

Clegg, designer of the valve used on the four operated railways, installed a demonstration railway at the Chaillot foundry, in the 16th arrondisement of Paris. The location seems to have been near la Pompe à Feu de Chaillot, which pumped water up from the Seine to reservoirs from which water could flow to fight fires. The Périer brothers (not the Periere brothers of the Saint-Germain atmospheric) who operated the water works also built steam engines, copying the designs of Boulton and Watt.

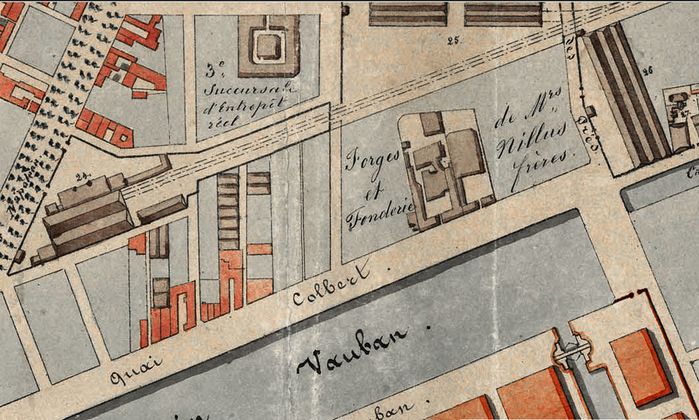

The map below, dated 1817, shows the Fonderie at left center.

— Amédée Martin, Plan routier de la ville Paris et de ses faubourgs, 1817.

I find it hard to match the map to modern streets, but it is not far north of the Trocadero. The next map square down would show the future site of the Eiffel Tower.

An additional demonstration of Clegg's invention was built at the Nillus brothers' foundry at Le Havre. The location is shown below, but at the present time this is an area cleared of all structures and awaiting new building. The railway terminus at Le Havre is still at the site shown at the left side, the track indicated by dot-dash lines.

1839 : Samuel Clegg at Southwark, London.

Another Clegg demonstration was built at the Samuda brothers iron works in Southwark. Hadfield describes the model shown to the public as a miniature railway, 180 feet long with a steep 10% grade, and a tube just over 3½ inches diameter, which could raise over 300 pounds of weight consisting of a car and two grown men, at 7 miles per hour. I do not know where this was. The Samuda business moved to the Goodluck Hope Peninsula at Lea Mouth in 1843, where Jacob Samuda was killed in November 1844, and then moved again to Cubitt Town in the Isle of Dogs in 1852.

1840 : The Lickey Incline.

In 1840 an incline two miles long at 2.65% (1:37.7) was opened on the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway. It was built against the advice of I.K. Brunel and George Stephenson that it was too steep for locomotive adhesion. Setting aside proposals for cable assistance, B&GR engineer William Moorsom ordered a 4-2-0 locomotive from the Norris works in Philadelphia of a type that had been shown capable of steep grades. After it proved its worth the company ordered many more. Yet Brunel and Stephenson were not totally wrong: here on the steepest grade on a main line in Britain, bank engines are still needed for heavy trains, but even so the expense of a cable (or atmospheric) system is avoided. All four atmospheric railways were built after the Lickey Incline, and the Dalkey and Croydon lines had much easier grades. Dainton Bank (on part of the South Devon that was never worked atmospherically) is almost as steep but for a shorter distance, and the Saint-Germain railway at 3.5% near the top was steeper by far and not routinely operated by locomotives until 1860.

1840-1843 : Samuel Clegg and Samuda Brothers at Shepherds Bush and Wormwood Scrubs, West London.

This was the demonstration atmospheric railway that brought attention from parties connected with the Dublin and Kingstown Railway, the Chemin de fer de Paris à Saint-Germain, and the London and Croydon Railway. The public were invited during its times of operation between June 1840 and March 1843. Among the passengers were Prince Albert and the scientific partners Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace.

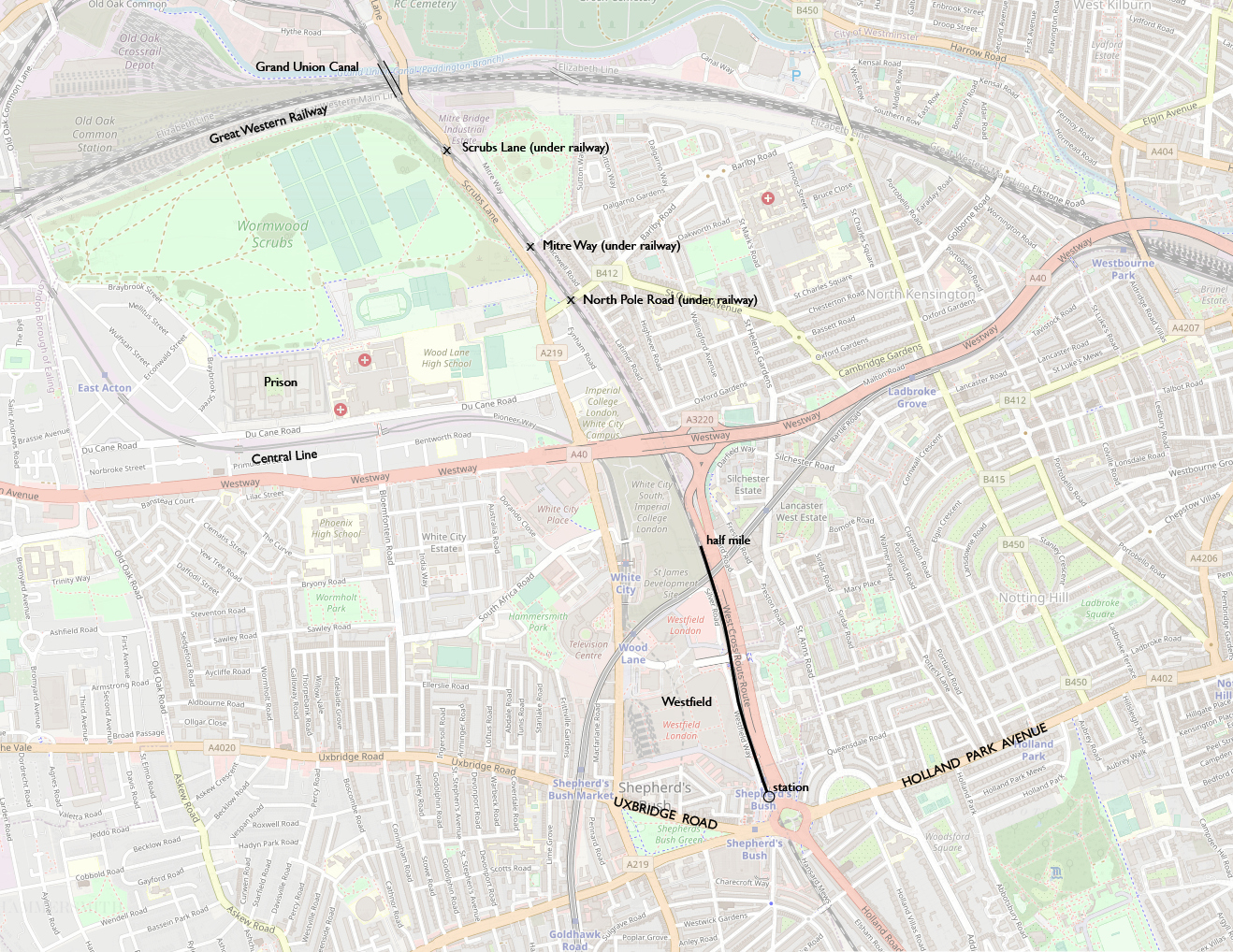

The atmospheric team leased a section of the unfinished Birmingham, Bristol & Thames Junction Railway, a very grand name for three miles of line intended to connect the Great Western and London & Birmingham railways with the inland end of the Kensington Canal (the canal alongside which Pinkus had built). The company name was changed to West London Railway by the time the demonstration opened, but the company still ran no trains. The lease allowed experimentation over 1½ miles between the Great Western crossing and Holland Park Avenue (Uxbridge Road). Hadfield reports the Samudas' disappointment that not much more than a half mile was ready for ballast. He also tells us that the engine house was on the west side, just north of the Scrubs Lane bridge, that the rails were cast-offs from the Liverpool & Manchester, and that the pipe was nine-inch. The pipe was cast in what became the usual length of ten feet (plus six inches for the socket).

A news article in The Times for June 13, 1840, two days after the first public test runs, places the entrance at the Uxbridge Road, the site today of the Shepherds Bush station of the Overground.

I consider that a reporter would be able to report accurately what road a station is on. But if that is where it was, it is hard to believe that the engine house was located at Scrubs Lane bridge, because it would add nearly a mile of useless pipe to be exhausted. Hadfield adds that "the experimental section ran from just south of the Great Western line alongside Wormwood Scrubs to the Dalgarno Gardens bridge," the latter being today Mitre Way. This stretch is less than a half mile, and the distance from the Uxbridge Road is impossible to reconcile with the newspaper story.

Some resolution may be found in A Treatise on the Adaptation of Atmospheric Pressure to the Purposes of Locomotion on Railways by Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda, 1841, in which he writes: "The system is in operation on part of the above line between the Great Western Railway and the Uxbridge Road, on an incline, part 1 in 120, and part 1 in 115. The vacuum-pipe is a half a mile long, and 9 inches internal diameter. The exhausting pump is 37½ inches diameter and 22½ inches stroke, worked by an engine of sixteen horses power." He includes measurements of speed that were taken at posts placed every 2 chains along the half mile, posts 1 to 14 on the 1:120 and 15 to 20 on the 1:115, and this is so precise that we can conclude that it was exactly half a mile and assume (I would say) that the engine house was not much past that distance.

Advertisements placed in The Times beginning on August 15 told the public:

The Atmospheric Railway may be seen in operation on the West London (lately called the Thames Junction) Railway, Wormwood Scrubbs, every Monday and Thursday, from 3 until 5 o'clock, and from actual workings it has been found that on this system increased speed and security are obtained. There is no possibility of accidents from collision, running off the road, or fire, and two-thirds of the working expenses and cost of formation of a railway are saved.

A different advertisement, repeatedly placed by The Times's compositors next to the one above, read:

Pneumatic or Atmospheric Railway, under patents granted to Henry Pinkus, Esq., the Inventor.... The public are cautioned against entering into contracts with any party or parties who, under a colourable variation, are endeavouring to pirate the present patents.As I mentioned, the differences were by this time only in the design of the linear valve. Whether Pinkus's would have worked better is not obvious, and in any event it was not proved in regular use.

The map below shows the general area of the half-mile atmospheric railway (black line) and its station.

After the atmospheric equipment was removed, the West London completed the railway for locomotive operation with a single track. Passenger service was provided from May to November 1844 at three stations: West London Junction (south side of the GWR level crossing), Shepherds Bush (north of the Uxbridge Road), and Kensington (north side of the Hammersmith Road). The area was not well populated, so a service connecting with GWR local trains was not much in demand. The half-hourly trains carried an average of one passenger. The station house at Shepherds Bush was a substantial two-story building on the west side of the line, located down a short lane from the Uxbridge Road. It opened 14 months after atmospheric operation ended, so it probably was built after the atmospheric. At any rate there is nothing left.

The West London finally became an important freight link in 1863 when it was extended along the path of the abandoned canal and across the Thames, but frequent passenger service did not return until 2008 when the railway became part of the London Overground. Construction of the present Shepherds Bush station destroyed all remaining trace of earlier station buildings.

Below is the brutalist Overground station at Shepherds Bush, on an appropriately gloomy day in 2018, at the approximate location of the atmospheric station and looking north along its route. The main entrance is behind this point, and the steps and footbridge ahead are for a secondary entrance to the gigantic Westfield shopping center.

Shepherds Bush Overground, Sunday, October 14, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

This is a place that does not attract tourism, so I feel I should mention nearby points of interest. If you cross the street to the other Shepherds Bush station, on the Central Line, and ride west, you will have the thrill of entering the section of rare right-hand running made necessary by track arrangements a century ago. After the train comes outside, you will reach the more readily viewed place where the tracks cross back to their normal positions. If you can't get enough, there is a footbridge offering a good view of the scene. You will not be the first to take the photograph. I did not do this, but the point is, you could do it.

If you then debark at East Acton you will find it is perhaps eight minutes' walk to the famous HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs. The online reviews are iffy: "Someone told me the food was good here. It is not." — "Nice enough place, but they wouldn't let me leave." — "Guide says category B. Certainly not up to standard." Your move. I didn't go there either.

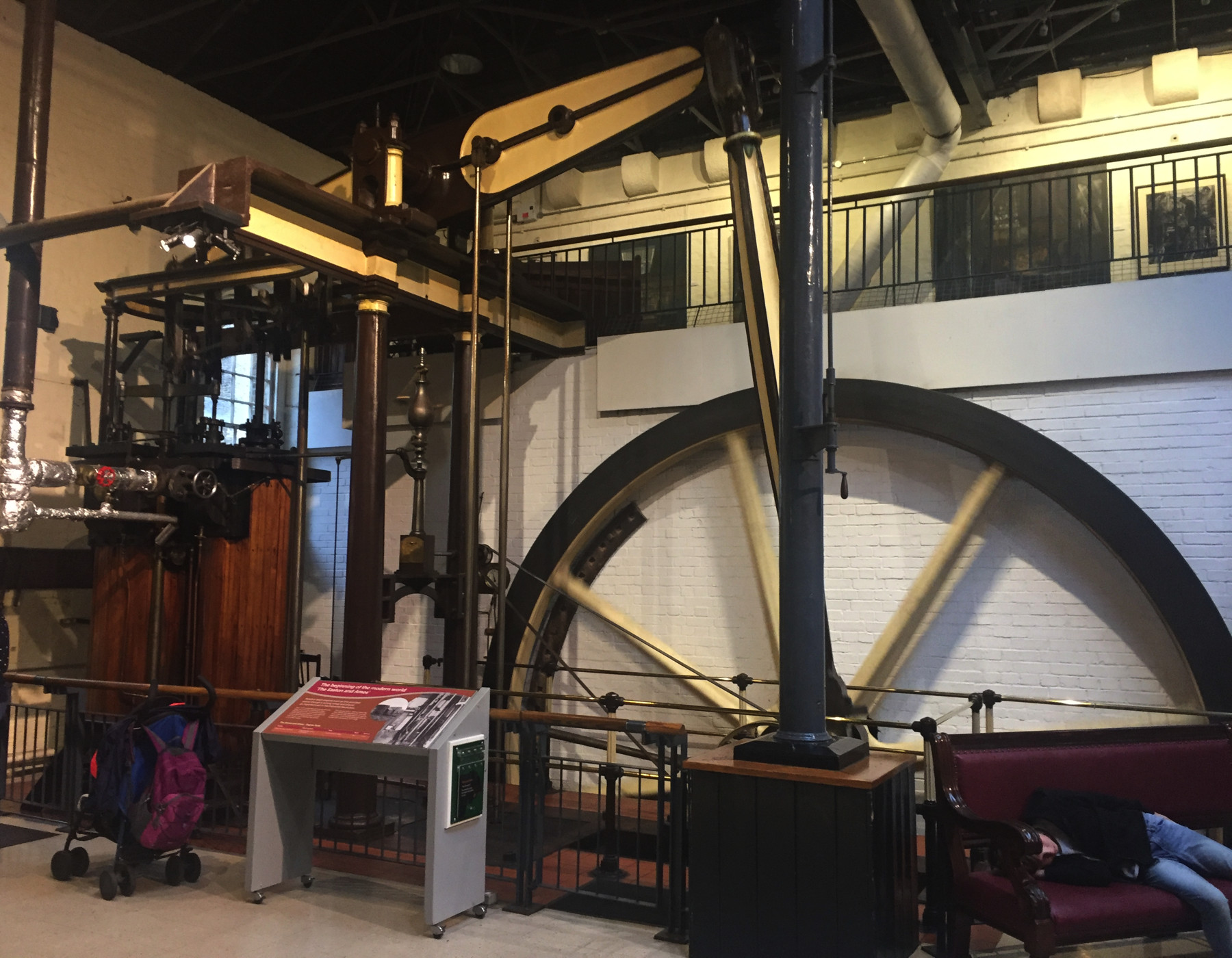

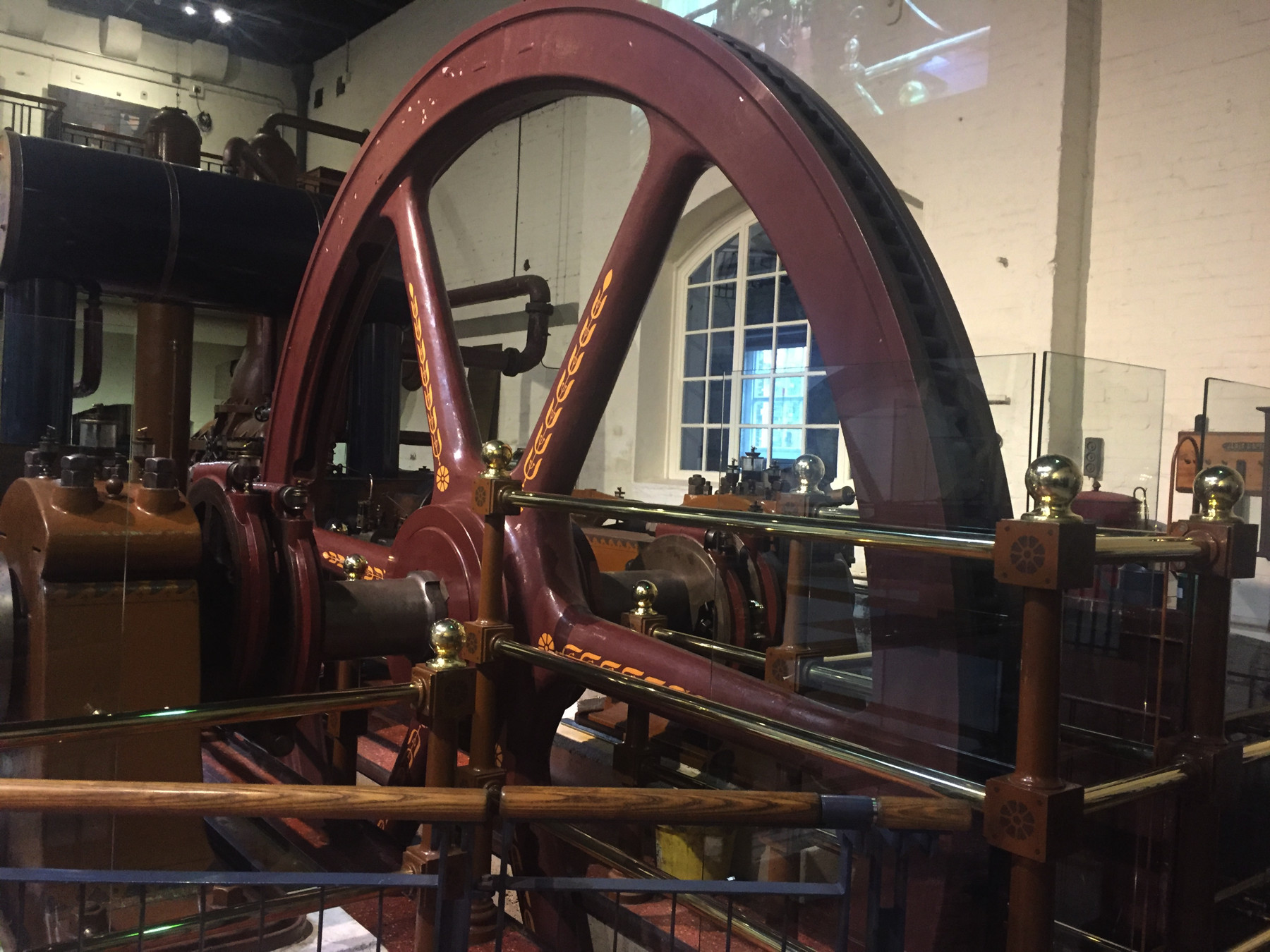

Where I did go, actually before I went to Shepherds Bush, was to the London Museum of Water and Steam, which is about a half hour west of Shepherd's Bush by bus. They have working stationary steam engines and boilers on display that are not very different from those that worked air pumps for the atmospheric railways. I wish I had read up in Clayton and Hadfield about the engines before visiting, because afterwards I realized many features they described are here. The museum building was a pumping station that pushed treated Thames water to central London.

The first picture below shows a Cornish engine with a rocking beam and the rotating valve rod (left center). The boilers were in a separate part of the building. I cannot explain the young man collapsed on the bench.

Museum of Water and Steam, Sunday, October 14, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

Museum of Water and Steam, Sunday, October 14, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

The museum also has a small locomotive that moves a train a short distance within the property. It's a nice ride. I was told that back in the day the rail carts on this particular property were moved by hand, but that many other waterworks did have engines similar to this one. Its namesake Thomas Wicksteed was an important figure in the London waterworks and sewage works from 1829 to 1851. Among other things he introduced use of the more efficient Cornish engine, and consulted with companies worldwide. This engine was built in 2009 and lays claim to being the newest working steam locomotive in the country.

Museum of Water and Steam, Sunday, October 14, 2018. © Joseph Brennan.

The museum is close to the Kew Bridge station for local trains from Waterloo, which was how I arrived. Reasons to go this way: see two level crossings of London streets, and hear the train robot announcing Isleworth as "izzlewurt" rather than "isle worth". Maybe those do not give much reason.

1844 : Dublin and Kingstown Railway, Kingstown to Dalkey.

Not strictly a demonstration, but representatives from other prospective atmospheric railways came to visit it. My pages begin here.

1844 : Alexis Hallette at Arras.

Hallette was one of the competitors for the Saint-Germain railway. On this page I mentioned his linear valve with hose-like "pneumatic lips." But where was his demonstration? It was at his foundry in Arras, 100 miles north of Paris. He began making parts to repair locomotives around 1830, and eventually built them new, one of which, from 1847, is in La Cite du Train at Mulhouse. I do not know where in Arras his foundry was.

1845 : Royal Polytechnic at London.

"The Atmospheric Railway, Daily at Work, carrying visitors, at the Royal Polytechnic Institution," read a notice in The Athenæum for June 14, 1845. "This interesting Model is lectured on by Professor Bachhoffer at One o'clock daily ; also on the evenings of Wednesdays and Fridays at Eight o'Clock, and on the evenings of Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays at Nine o'Clock. The Working of the Model always follows the Lecture. It is also worked at Four o'clock, and at other convenient times."

The article does not say whose invention was being shown, so it may have been Pinkus or Clegg and Samuda. Although it is called a model, it was "carrying visitors." The Institution was at 309 Regent Street, with a large exhibition hall. It is still located at that address under the name of University of Westminster, but the building was "rebuilt" in 1912, so I do not know to what extent one could stand today on the site.

1846 : London and Croydon Railway, Forest Hill to Croydon

Atmospheric operation began in January. My pages begin here.

1846: Hédiard at Saint-Ouen, Paris

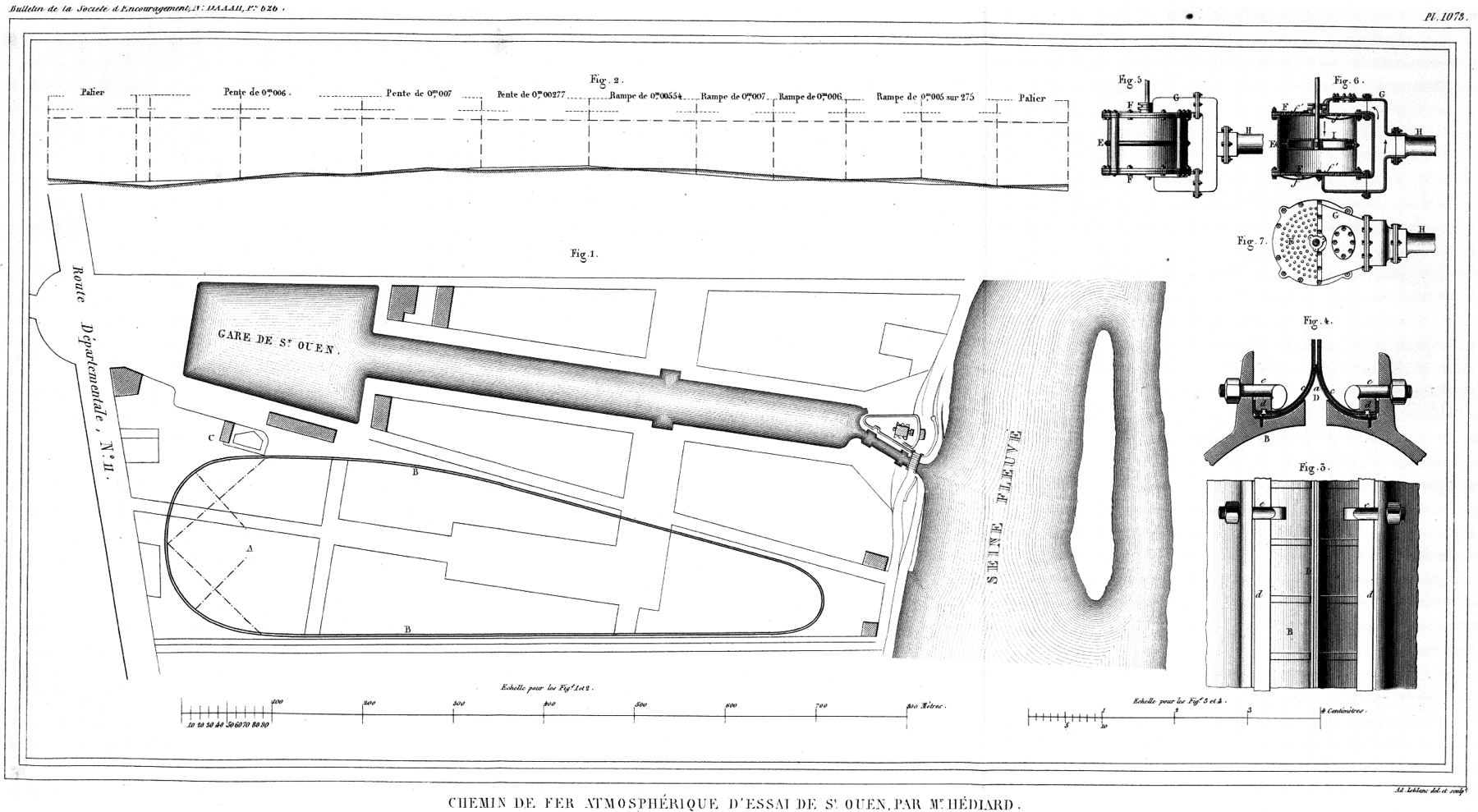

Hédiard (first name not given) patented in France in 1844 a longitudinal valve closed by springs of steel, which was scarcely different from Pinkus's design of 1836. The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette in May 1845 quoted the Railway Herald calling it "one of the most impracticable plans proposed yet". But by that date he arranged to have a demonstration line built at the port of Saint-Ouen outside Paris. It was a loop about a mile long with an atmospheric pipe that powered only about a third of the distance. The pipe was the usual 10 feet in length with a internal diameter of 15 inches. The train was composed of an articulated set of a piston carriage and two trailers.

In the diagram below, the engine C powered the pipe between B and B. It is not clear whether the demonstration train ran only in that section. The site near the Seine was probably level, but could the train really coast the unpowered two-thirds of a mile, especially with the sharp curve retarding its speed? Figure 4 shows the lips, and figure 5 is a view of them from directly overhead, both showing the fixtures holding the lips in place.

— Bulletin de la Société d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale, 1848.

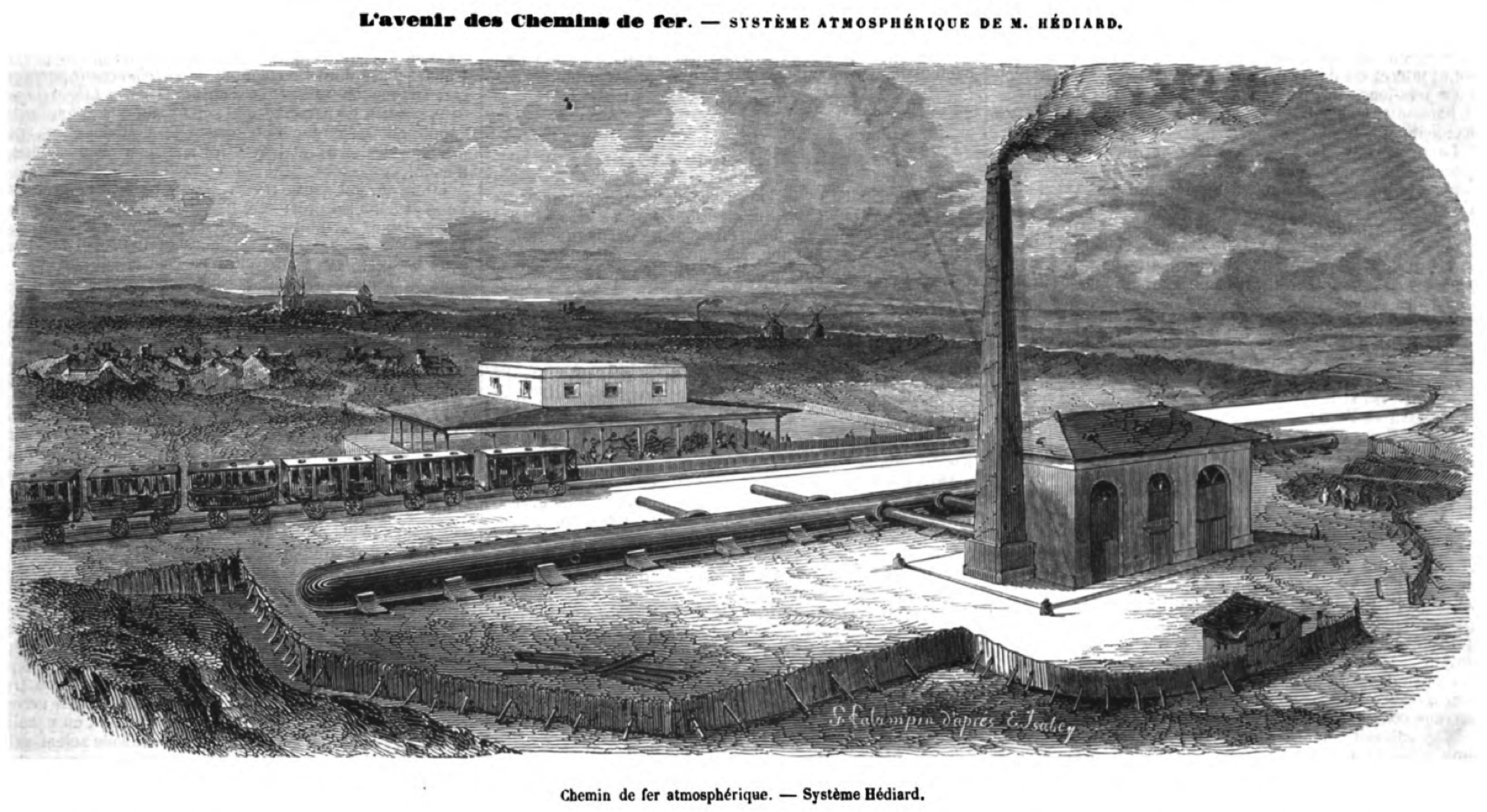

From the same year we have an illustration, a rarity for these demonstration railways. It does not match the description or the diagram, and the arrangement of pipes from the engine house does not make sense to me at all.

— L'Illustration, Journal Universel, September 16,1848.

The two publications above were almost too late. By October the whole layout was gone.

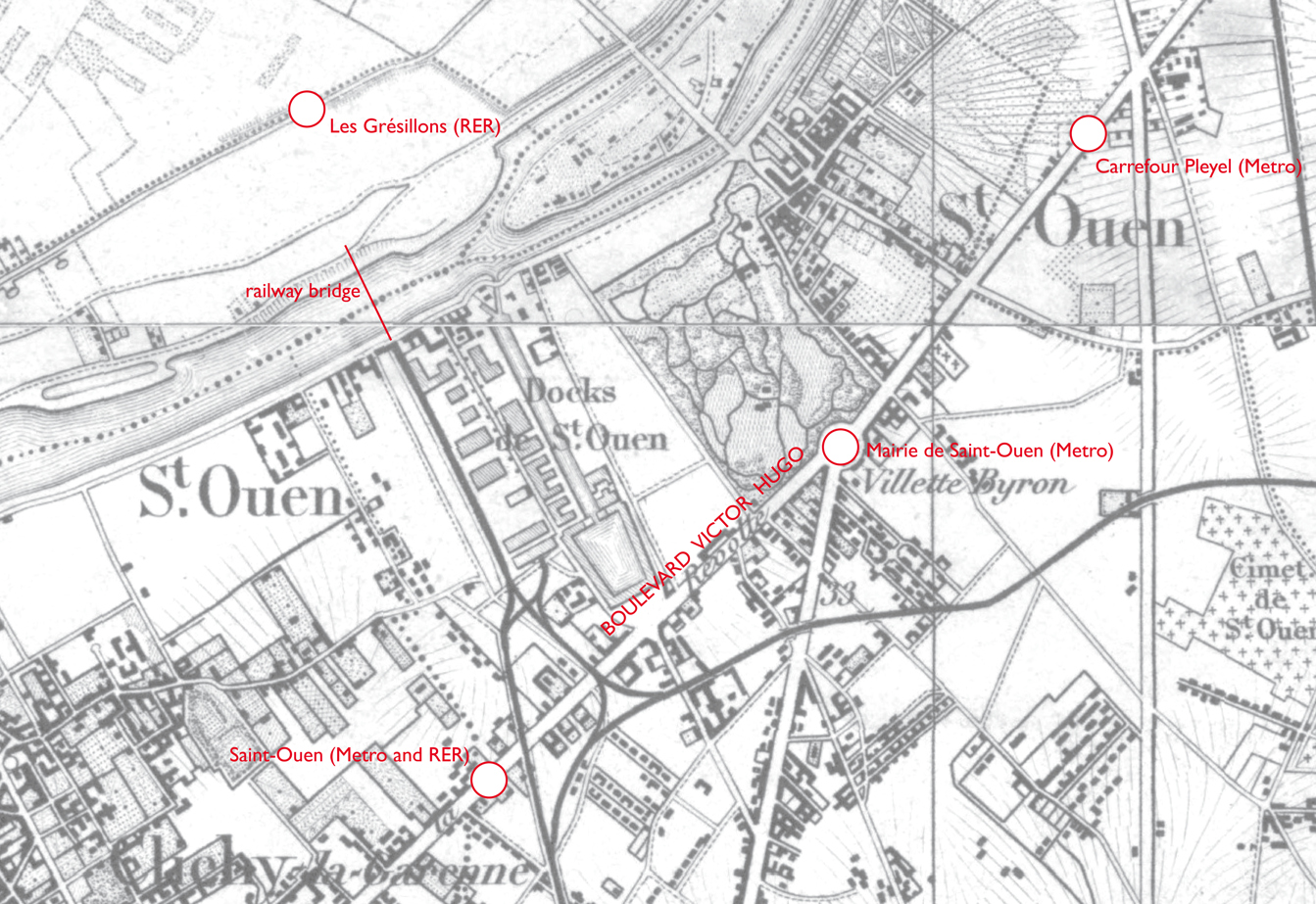

The diagram above is rotated quite a bit from the usual north at the top, but the location can be identified on old maps by the distinctive shape of the docks at Saint-Ouen, shown here on a map from two decades earlier. The trapezoidal space east of the dock was used for the demonstration line. This is now a district of mixed industrial and residential buildings and the docks were filled in long ago. I have added in red some modern names and landmarks. see here.

— Plan routier de la ville Paris et de ses faubourgs, 1817.

1846 : Alexis Hallette at Peckham, London.

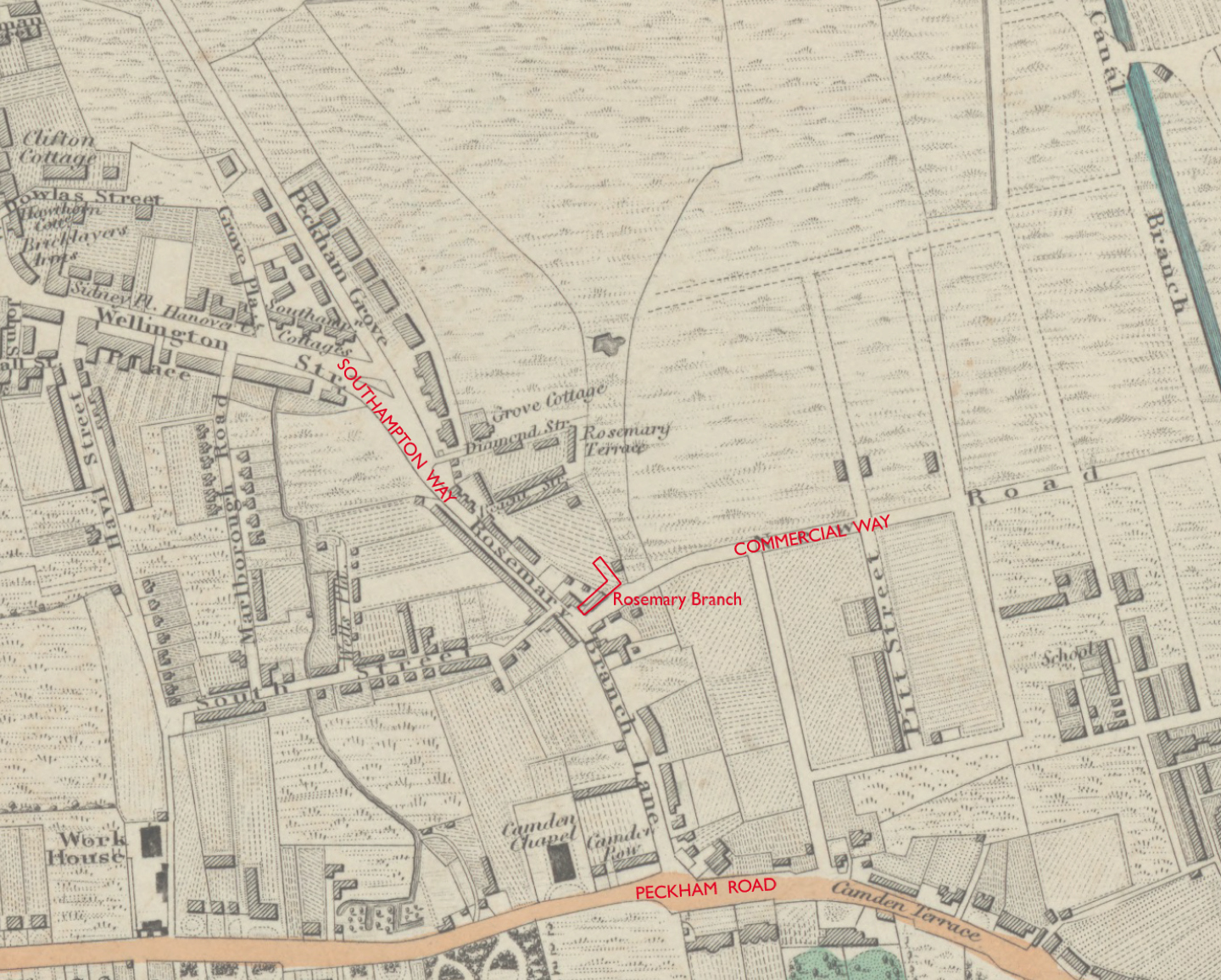

In 1846 Hallette was still hoping a railway would try his "pneumatic lips" design rather than more complicated Clegg-Samuda valve. He built a demonstration line 400 feet long in the grounds of the Rosemary Branch public house in Peckham, south London. It was probably narrow gauge. It had a tube of only five inches and a small car that could carry four people at up to 12 miles per hour. It was obviously not full scale. Tickets had to be purchased, inconveniently, at the Atmospheric Railway and Canal Propulsion Company office in Old Broad Street. The average customer at the Rosemary Branch could only watch.

The pub had quite a history. From Old and New London, 1878:

The "Rosemary Branch" tavern, in Southampton Street, which stands at the junction of the Commercial Road, although possessing but a local reputation at the present time, was a well-known metropolitan hostelry at the commencement of the century. The old house, which was pulled down many years ago, was a picturesque structure, with rustic surroundings. Its original sign, if we may trust an entry in the churchwardens' accounts for 1707, appears to have been the "Rosemary Bush" ...

Tradition has it, that whenever the landlord of the old house tapped a barrel of beer, the inhabitants for some distance round were apprised of the fact by bell and proclamation! When the new house was erected it was described, in a print of the time, as an "establishment which has no suburban rival." The grounds surrounding it were most extensive, and horse-racing, cricketing, pigeon-shooting, and all kinds of out-door sports and pastimes were carried on within them... The grounds have now been almost entirely covered with houses.

The "Rosemary Branch" is by no means a common sign for a public-house; but this house at Peckham is perhaps one of the best known in the metropolis. Rosemary was formerly an emblem of remembrance, much as the forget-me-not is now. "There's rosemary, that's for remembrance," says Ophelia, in the play of Hamlet; and, in the Winter's Tale, Perdita says:

"For you, there's rosemary and rue; these keep

Seeming and savour all the winter long;

Grace and remembrance be unto you both."

The map below shows the Rosemary Branch at about 1846. The base map is 16 years earlier, but it shows the "grounds surrounding it" which were probably those to the north. The atmospheric railway must have been somewhere in that location. The L-shape of the public house, in red, is based on a later Ordnance Survey map, but the corner location was that of the oldest part. Wellington Street and Rosemary Branch Lane were later Southampton Road and now Southampton Way. The New Road, at the corner, was later Commercial Road and now Commercial Way.

— Christopher & John Greenwood, Map of London ; made from an actual survey, 1830.

However rare the name may be, today there is a Rosemary Branch in Islington that is not this establishment in Peckham.

Hallette's demonstration opened in May of 1846 and was the last significant attempt. The Croydon railway was already started, and the Saint-Germain and South Devon were prepared to start the next year, all with the Clegg-Samuda patents used at Dalkey or small variations of them. The Croydon closed in 1847 and the South Devon in 1848. The atmospheric age was passing. The Dalkey railway ended in 1854, to permit through locomotive working. The Saint-Germain held on the longest because of the steep grade, but it too abandoned atmospheric power in 1860 when the company had to choose between replacing the aging equipment or going with the more standard method of locomotives and bank engines.