London and Croydon Railway

Croydon

In which Joe sheds light on the history of the flyover and the West Croydon terminus, and finally finds a genuine relic of the atmospheric age and determines its provenance, and ends with a review of why atmospheric railways were hopeless.

Explorations: Tuesday, 9 October 2018, and Tuesday, 18 June 2019

Journey: New Cross Gate to West Croydon, London Overground

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- John T. Howard Turner, The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway , volume 1, "Origins & Formation", B.T. Batsford, 1977.

- John T. Howard Turner, The London, Brighton & South Coast Railway , volume 2, "Establishment & Growth", B.T. Batsford, 1978.

The outermost section of the London and Croydon Railway's atmospheric railway included a feature that seemed to catch the imagination of the public: the flyover. At this early date in railway history, wherever a railway divided into two branches, tracks simply crossed on the level. The two tracks coming down from London diverged into two to Croydon and two to Brighton. An up train from Brighton crossed the path of a down train to Croydon. It could be inconvenient when one of the trains had to wait while the other crossed, and there was some danger if signalling failed. But the atmospheric track could not cross another track at all— the pipe would be in the way— so it had to go up and over the Brighton tracks.

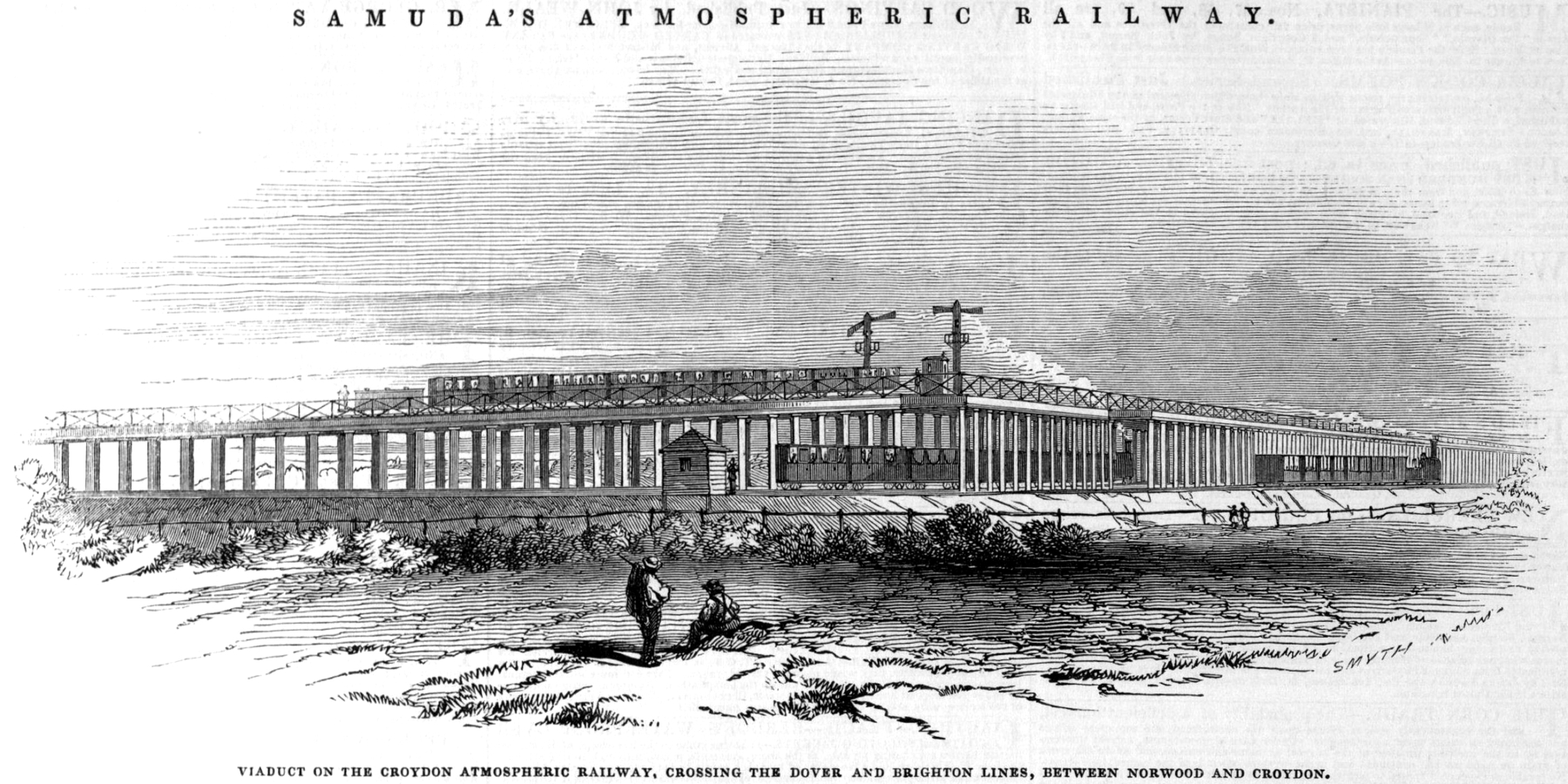

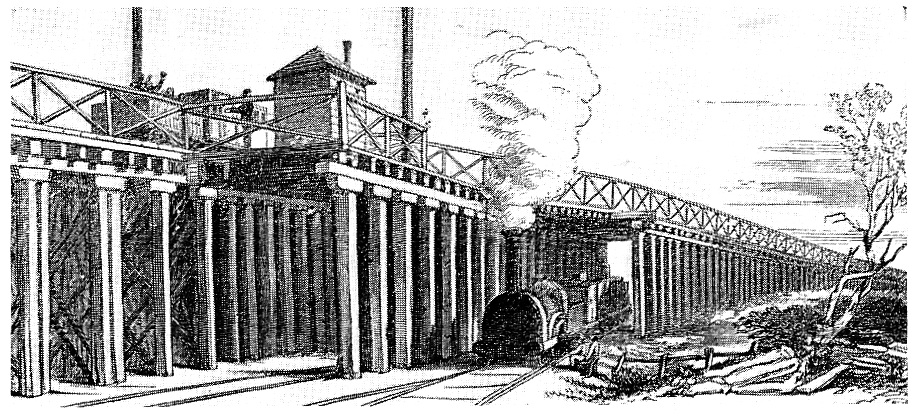

The flyover was built of wood, to save money but also in the belief that only lightweight atmospheric trains would cross over it. For the same reason the grade on each end was allowed to be a hefty two per cent. Both illustrations below emphasize the advantage that a Brighton train can pass at the same time.

— Smyth, Illustrated London News, 11 October 1845.

— source unknown, via Hadfield.

Both illustrations show a signal cabin at the top of the bridge. I don't know what it would be for. The atmospheric system could never pull trains toward each other on the flyover. The similar signal cabin at ground level, in the first picture, makes sense. Both pictures show something that is not the piston carriage at the nearer end of the train, and the lower one has a man at the signal cabin and someone in the nearest car waving an arm. I can't explain that either, but the first image at least predates the opening, and they may both be based on an earlier design of piston carriage, as I will show farther on.

If there was a Frequently Asked Questions list for this flyover, the number one item would be why the company laid the atmospheric track along the east side of the old railway, making the flyover necessary, when laying it on the west side could have avoided the trouble. I know I wondered about this myself for many years. The answer is two words: Bricklayer's Arms. I spent a little space on that branch back on the Forest Hill page for a reason. Avoiding the flyover here would simply have required one there instead.

Yet putting the atmospheric on the west side still seems better to me, because of the London and Greenwich viaduct. The plan was to widen it on the north side by one or two tracks, and shift the Greenwich trains toward that side. Was it best for the atmospheric track to come in between the two companies' standard tracks, or along the south side? I would have to say the latter, because then the standard tracks would be next to each other, without the barrier of an atmospheric pipe, and it would be possible to install switches to allow locomotive trains to use any of them during maintenance works. Am I forgetting something?

The first winter and spring brought problems with the engine houses ; the summer, problems with the linear valve ; and now the autumn, problems with water. Steam engines need a good supply of water. Letters to the editor of The Times complained especially about trains stalling going up the bridge, for lack of enough vacuum. The piston carriage now routinely carried a rope, so that it could advance alone over the top and pull its train by rope as it ran down the other side. In other cases passengers were asked to alight and push the cars one at a time over the top, and let them coast down to the piston carriage. And sometimes a steam locomotive came to do the push. This was a ridiculous way to run a railway.

And yet ridership was increasing during 1846. By late in the year rains must have come, or anyway the shortage of water was solved, and now frost made the leather flaps hard, and they did not seal properly. There seemed no end to the shortcomings. Howard Clayton quotes The Times in February 1847:

Owing to the snow on Sunday getting into the tube the various trains after 5 o'clock had to be conveyed by the locomotive. At 9 o'clock an attempt was made to work the down train by atmospheric power, but in consequence of a stoppage a locomotive was sent after the train to assist it on its journey, when one of the men employed to superintend the closing of the valve, not being aware of the arrangement, and, it is supposed, not expecting a locomotive on the atmospheric line, was fulfilling his duty, and before he was observed the engine ran over him, almost crushing him to pieces.The man died of his injuries. It was becoming clear that the atmospheric system was far from trouble-free. The directors of the newly consolidated London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, formed in July 1846, had already decided not to use atmospheric power on the Epsom extension. The seasonal problems with leather flaps and water supply and the inability of the Forest Hill engine house to pull trains reliably up from New Cross together sealed its doom. The atmospheric system was abandoned on 4 May 1847.

The company removed the atmospheric equipment quickly. The 24 July number of Railway Chronicle has an advertisement listing for sale engines, pumps, some tons of cast iron pipe, about 12 miles of longitudinal valve, the same length of iron rods, and bolts and screws to fit them.

The flyover was too steep and too flimsy for reliable operation by locomotives, so it was removed early on, and so was the atmospheric pipe. In his The London, Brighton & South CoastRailway, volume 2, John Howard Turner reports that by 1849 the former atmospheric track had been made the down line, and the two others were up lines. The unequal capacity was rectified in 1854 by the addition of a fourth track along the west side.

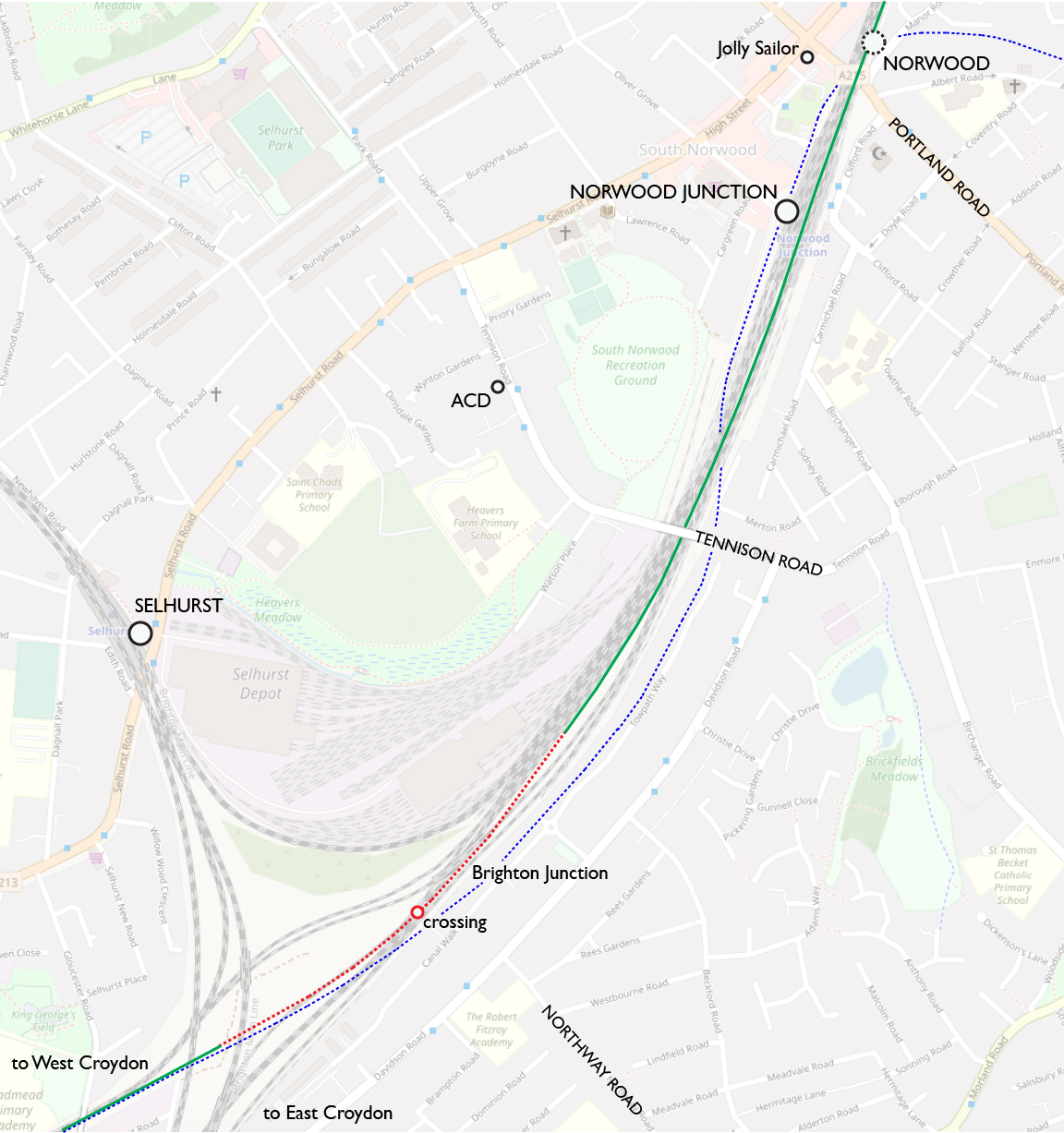

Norwood Junction station opened on 1 June 1859, replacing Norwood. From there and past the bridge under Tennison Road the site of the atmospheric track, while uncertain, must be toward the east side. Beyond that point the introduction of a new LB&SCR route to London Victoria via Selhurst led to many changes in alignment. In the map below I will make an attempt at showing where the atmospheric was.

— Base map © OpenStreetMap contributors.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan are

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Green: probable location of the atmospheric track. Red: possible

location of the flyover. Dark blue: site of the Croydon Canal.

The green location of the atmospheric is probably right, and at the lower left, on the way to (West) Croydon where the railway was on the canal alignment, it is exactly right. The location of Brighton Junction is best guess. At ground level the two tracks from London diverged on the level to two double-track branches. The atmospheric track went up and over at the crossing, the location of which is shown also as my best guess. I estimated the height as twenty feet, so then the approaches at the reported two per cent grade would span one thousand feet each, and that is what I show on the map. The crossing and therefore the approaches could have been a little bit north or south of the location shown.

A map in Howard Turner's volume 2 showing conditions in 1860 includes a new flyover carrying the down West Croydon track over the Brighton main line, but it was located much farther north, about where I show the end of the atmospheric flyover. By 1862 this down track also had a branch toward Selhurst that crossed over the other tracks to meet the new main line to London Victoria from East Croydon. Many years later, further construction relocated the West Croydon branch in this area to bulge to the northwest, as you can see on the base map. The satellite view in Google Maps shows evidence of the old straighter alignment.

To acknowledge "The Norwood Builder" I show also at ACD the house of Arthur Conan Doyle from 1891 to 1894 on Tennison Road. The story was a later one published in 1903, but recalling this neighborhood, Doyle mentions in it Norwood Junction station and the Anerley Arms public house.

CROYDON

From Gloucester Road, lower left on the map, it is less than a mile to West Croydon station. The station is at the edge of the central business district, a spot determined by a large block of property that had been the terminus of the Croydon Canal. Here and not in the confined space at London Bridge were the storage tracks and maintenance shops for the railway, and a station house appropriate to the only large town it served. The canal owned a plateway running from here down what is now Tamworth Road to meet the Surrey Iron Railway, but the L&CR never built on it.

The West Croydon branch (from Norwood Junction) has always had two tracks. The atmospheric took over the down track, leaving only one for locomotives, but that was all right since the plan was for the atmospheric to take all the passenger traffic to Croydon, and to Epsom when the extension opened. The open cut from Gloucester Road to St James's Road, the last bridge before the station, has not changed much since 1839, and at the latter bridge, sometimes called Spurgeon's Bridge, is a stone abutment on one side that was built for a canal bridge. A public footpath on the former towpath is still open within these few blocks.

The engine house at Croydon was located on the east side of the railway north of Croydon station, within the block now occupied by a large modern building called Interchange. Here is the engine house, below. The building in the distance on the right might be the station, for which I have no image to use for comparison.

— Illustrated London News, 11 October 1845.

A sketch very similar to this illustration appears in Howard Turner's volume 1 as a drawing of the Norwood engine house. While all of them were the work of the same architect, W.H. Breakspear, the engine houses were sufficiently different to identify the drawing as the Croydon engine house.

Howard Turner passes along a note in Herapath's Railway and Commercial Journal that by November the stalk at Croydon had to be removed because of damage from vibrations by "the violent and desperate working of the engines"— and please note that this was before regular passenger service even began in January.

How did they handle atmospheric trains at the terminal? Howard Turner gave his thoughts.

It is possible that, by making use of gradients or by introducing artificial inclines, gravitational help may have been given to the movement of piston carriages at termini, but tow-roping by horses or man-handling were probably the normal methods of 'shunting' and of getting the piston into the pipe at the start of a journey. In the Author's opinion, such slow and complicated terminal working, which must have been anathema to practical railway operating staff and those in command of them, must sooner or later have brought an end to atmospheric working on a busy line, no matter how reliable and effective train running on a plain road might eventually have become.Well said.

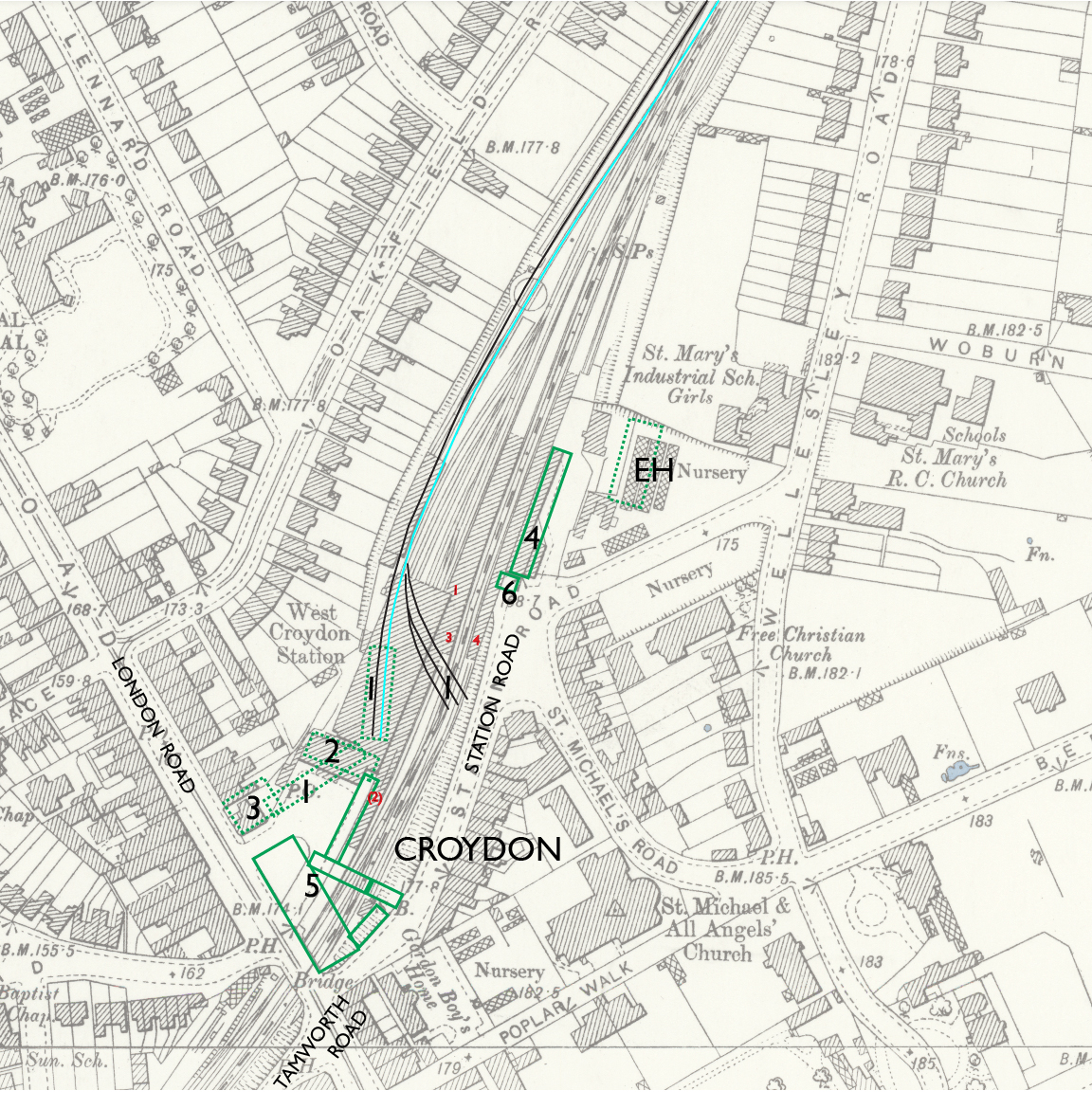

The station site has been altered many times, as shown in the map below.

— West Croydon station, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1898. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Based on "Conjectural map of Canal and Rails at West Croydon", in Croydon's Transport Through the Ages, ed. John Gent, Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society, 2001.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan: approximate site of engine house (EH), atmospheric track (light blue line), other track from 1839 (black line). Black numbers are stages of work (1 1839, 2 and 3 1847, 4 1860, 5 1935, 6 2012. Red numbers are platform numbers.

The number 1 indicates the terminus of 1839. Left to right, the long station house alongside a carriage road, the trainshed, and engine sidings. Track of 1839 is shown in black, except that used by atmospheric trains which is in blue. The pipe must have ended approximately opposite the engine house, so that it did not block the sidings.

In 1847, after atmospheric operation had ended and trains to Epsom had begun, everything from 1839 was replaced. Besides the changes the other reason for rebuilding was a fire in September 1846 that caused heavy damage to the station and destroyed some rolling stock. A new station house indicated as 2 stood at the end of an enlarged forecourt (building 1 swept away), with a carriage shed hidden behind it. Another railway building was added at 3. The Epsom branch left the original railway north of the station and passed through what are now platforms 3 and 4 (red numbers). As you can see the new carriage shed and Epsom line wiped out the old trainshed and engine sidings, but opened up property along the west side that was used instead for similar purposes. The base map shows in that space many sidings, a work shop building, and a turntable.

4 indicates a secondary station house on Station Road that may date from 1860. It had direct access to the down platform (red 4) and a foot tunnel to the other side that served platforms 1, 2, and 3. Although it was discontinued some time later, the buildings survived as commercial premises, and they are now the oldest remaining structures of West Croydon station.

5 indicates the Art Deco concrete station building that was completed in 1935, replacing buildings 2 and 3. Its main entrance on London Road still serves that function. A secondary entrance not far up Station Road was added at the same time or not long afterwards, but was closed later, possibly in the 1960s.

It took until 2012 for a new entrance 6 to be provided at the north end of the station, opposite the Croydon bus station. It adjoins the long-closed entrance 4.

The combined London, Brighton and South Coast Railway in 1846 had two stations called Croydon. This name collision did not wait until 1923 to be resolved, but it did take six years, during which this one was sometimes known as Croydon Town. It was officially renamed West Croydon in April 1852.

The platform numbering at West Croydon has become another Frequently Asked Question. Why are there only platforms 1, 3, and 4? The missing platform 2 was at the south end of platform 3, alongside the end of the track that ran to Wimbledon via Mitcham, a service that operated from October 1855 to May 1997. After that, some of the former track bed was filled in to make platform 3 come down closer to the station building. The Wimbledon line included some of the Surrey Iron Railway route and has itself become part of a Tramlink line. Below is a peek at what remains of platform 2, back there on the left, beyond the lengthened platform 3. "The platform structures are of little interest and could be upgraded," says the Heritage Audit of the London Overground. No kidding.

MUSEUM OF CROYDON

If you have followed this journey as far as West Croydon, I respect your persistence, and maybe I can make up for it. All four engine houses are gone, and everything has been changed. But... there are things to see in Croydon. You need to go about a half mile. Walk down the wide pedestrian street called North End, busy with shoppers, and turn left at Katherine Street. Not far is the Croydon Town Hall and its great clock tower, and inside that is the Museum of Croydon.

The museum has a good exhibition of relics from Roman and Saxon days. It is an impressive array of things found as individuals or the authorities dug into the ground during ordinary landscaping, paving, and building construction.

What I found even better is a large room full of objects of daily life donated by Croydon residents, spanning a hundred years since the first world war. This is exactly what a town museum should have. A brilliant idea and execution. While my American experience knows only a few of the specific brand names, I recognized in the appliances and toys and posters many things like those I remember.

The first remarkable thing I want to mention is the Trojan 200, a "micro" three-wheeled car built in Croydon from 1960 to 1966 by Trojan Limited, a company that had made small motor cars since 1920. The design was that of the Heinkel Flugzeugwerke (yes, "airplane works") and built by them in Germany as the Kabine from 1956 to 1958, after which the Trojan company bought the rights to the design. A type known as a bubble car, it was a very lightweight vehicle. With a mighty one-cylinder engine powering the rear wheel, it was said to achieve 100 miles per gallon and a top speed of about 45 miles per hour. With three wheels I would not want to exceed that anyway. Because the only door was at the front, the roof had a canvas-covered opening as an emergency exit in case of collision. Please forgive the odd lighting in the museum.

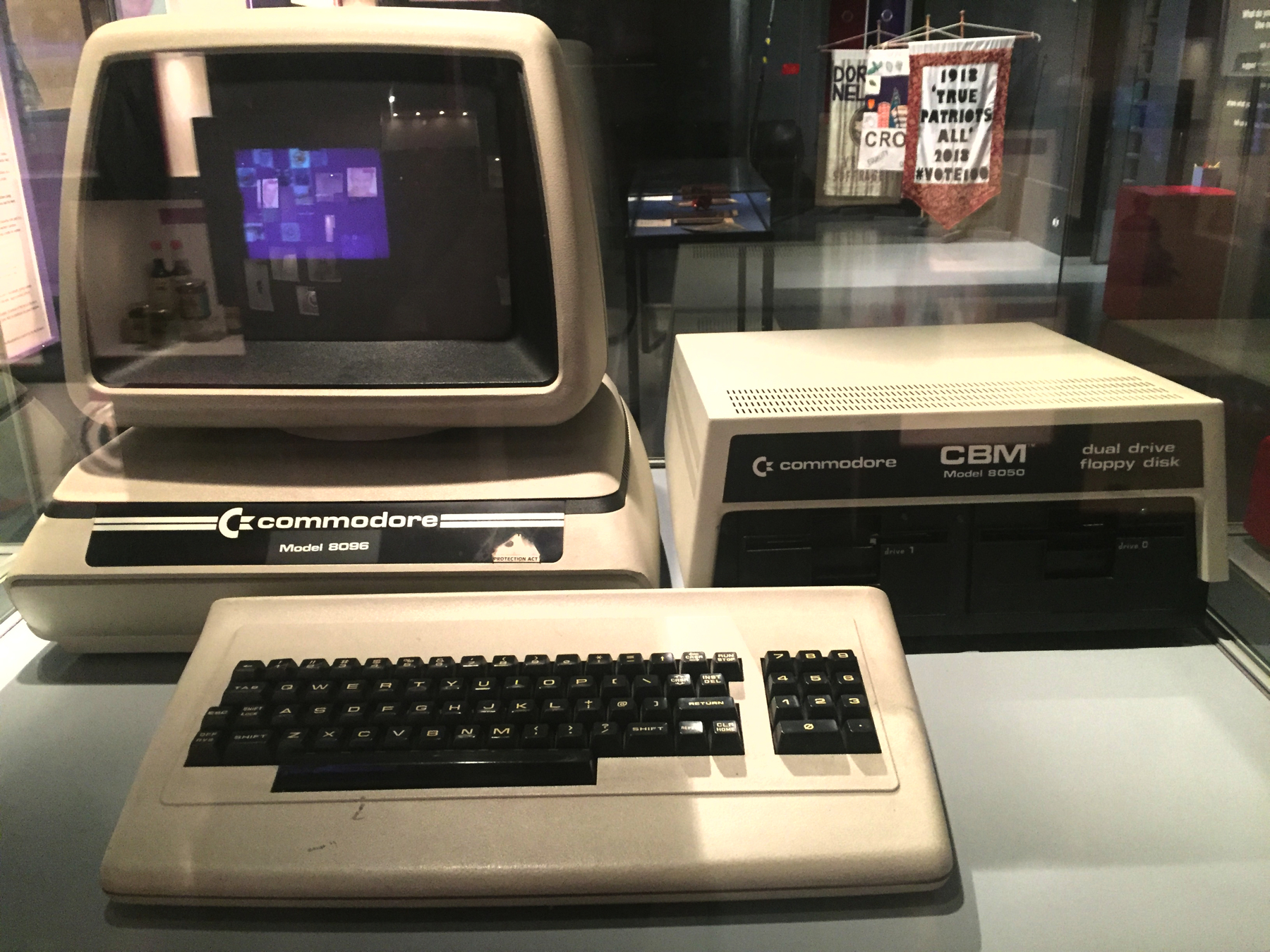

Next up, we have a Commodore PET (Personal Electronic Transactor) 8096, with an 80 by 25 character display and 96 KB of memory, circa 1981. On the right is the 8050 drive for two 5¼ inch single-sided floppy disks, from the same date. A card nearby revealed that these very machines were used by the Croydon Library.

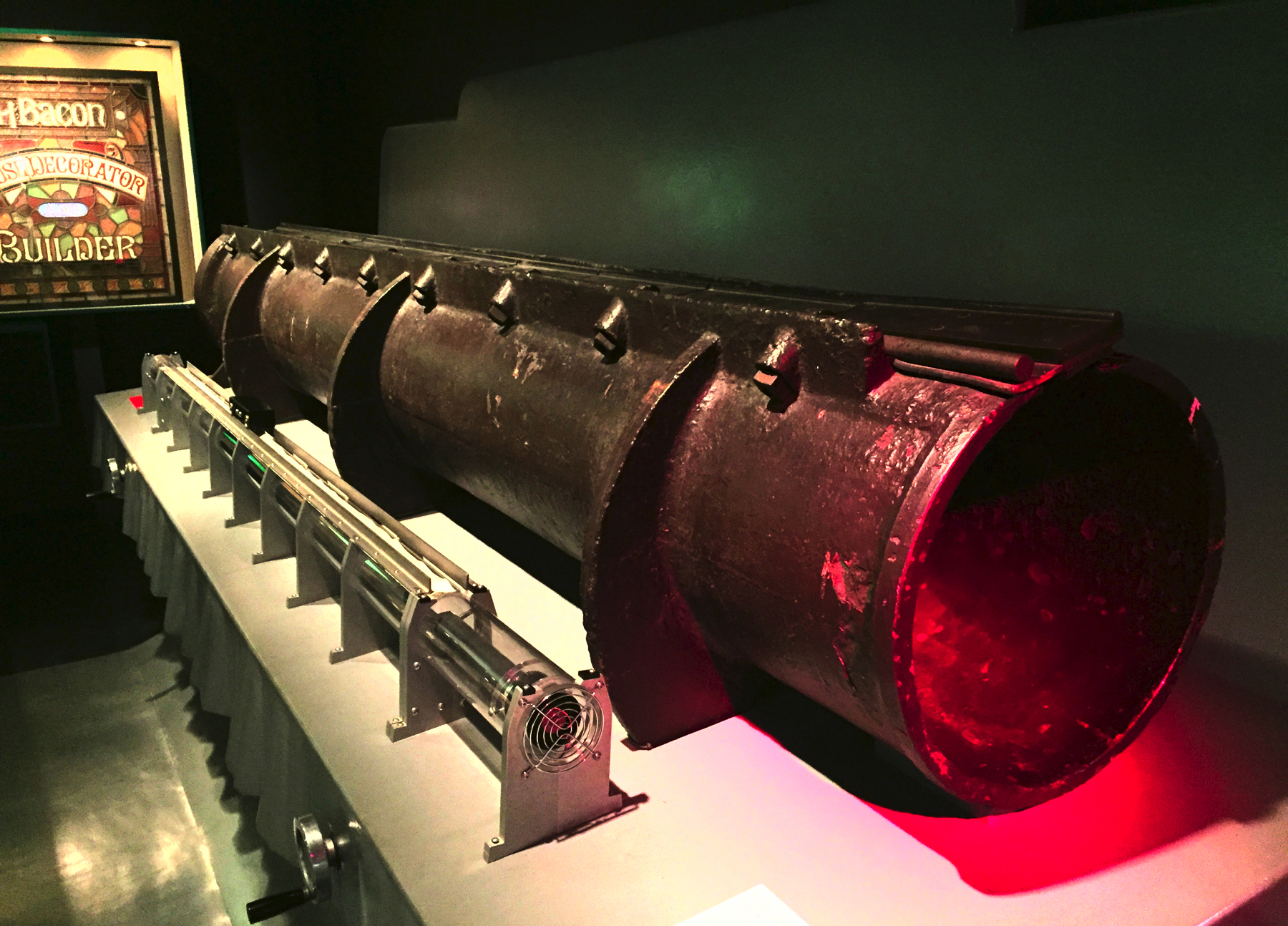

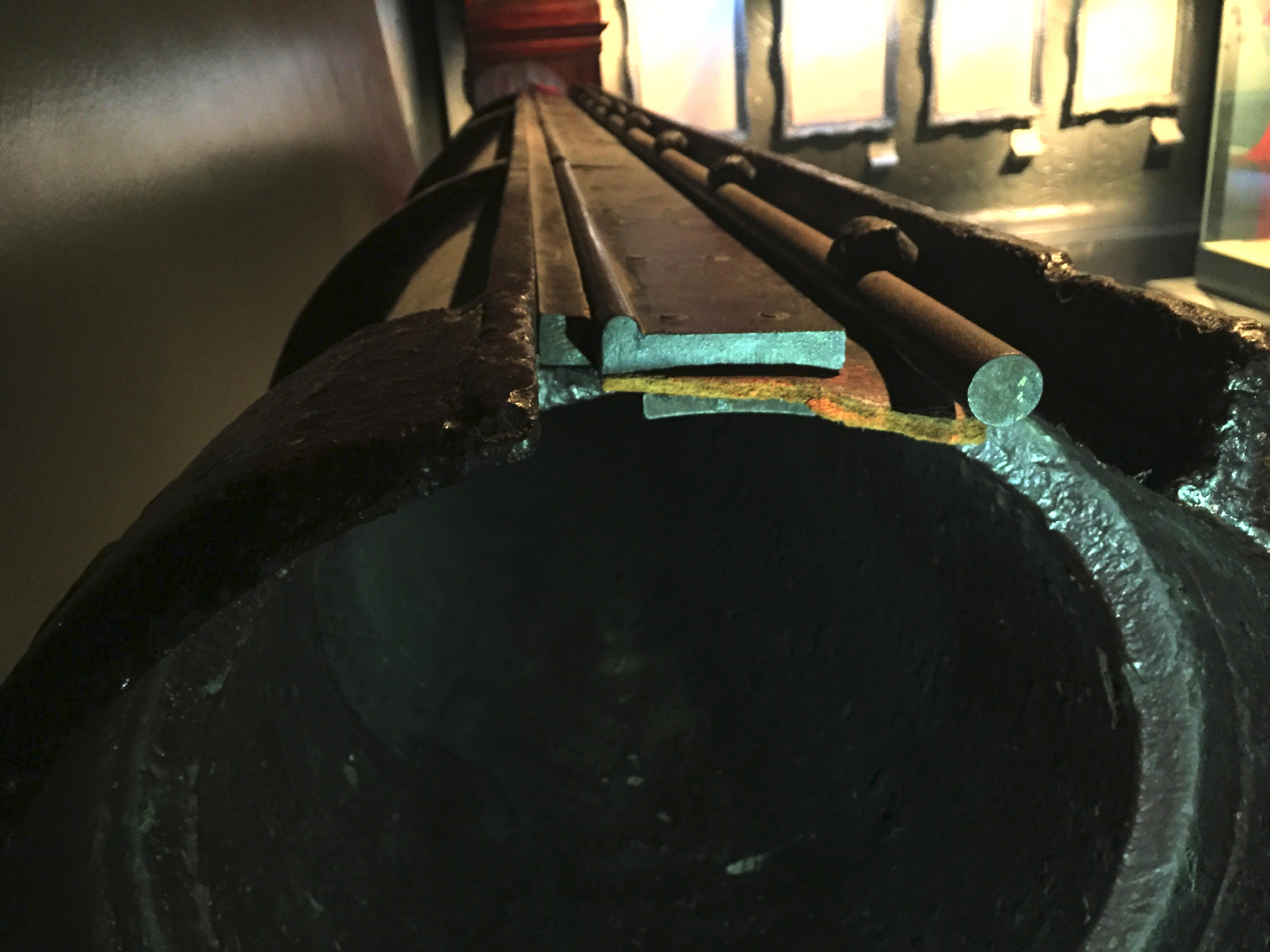

Of course there is something more important on display— the only surviving piece of London and Croydon atmospheric pipe! It's a full ten-foot six-inch section, the length as manufactured, three ribs and fifteen inches (internal) diameter. The real deal. The far end has the wider opening that would fit around the plain end of the next pipe, overlapping by six inches. I wonder what organic material they used to seal the joint.

I was amazed that the leather could have survived so long. The old man at the museum entrance had told me a little about the pipe, things I already knew, but I liked him almost immediately and listened politely. That's a good thing to do. Maybe he would tell me something I didn't know. It's not a busy museum. A calm place to take your time and keep the mind open, as I did with the collection of ordinary life. After I saw the leather I went back and told him, and he went back in with me. He allowed me to touch it and bend it gently to see how stiff it was. It was pretty stiff. The usual museum won't let you touch things.

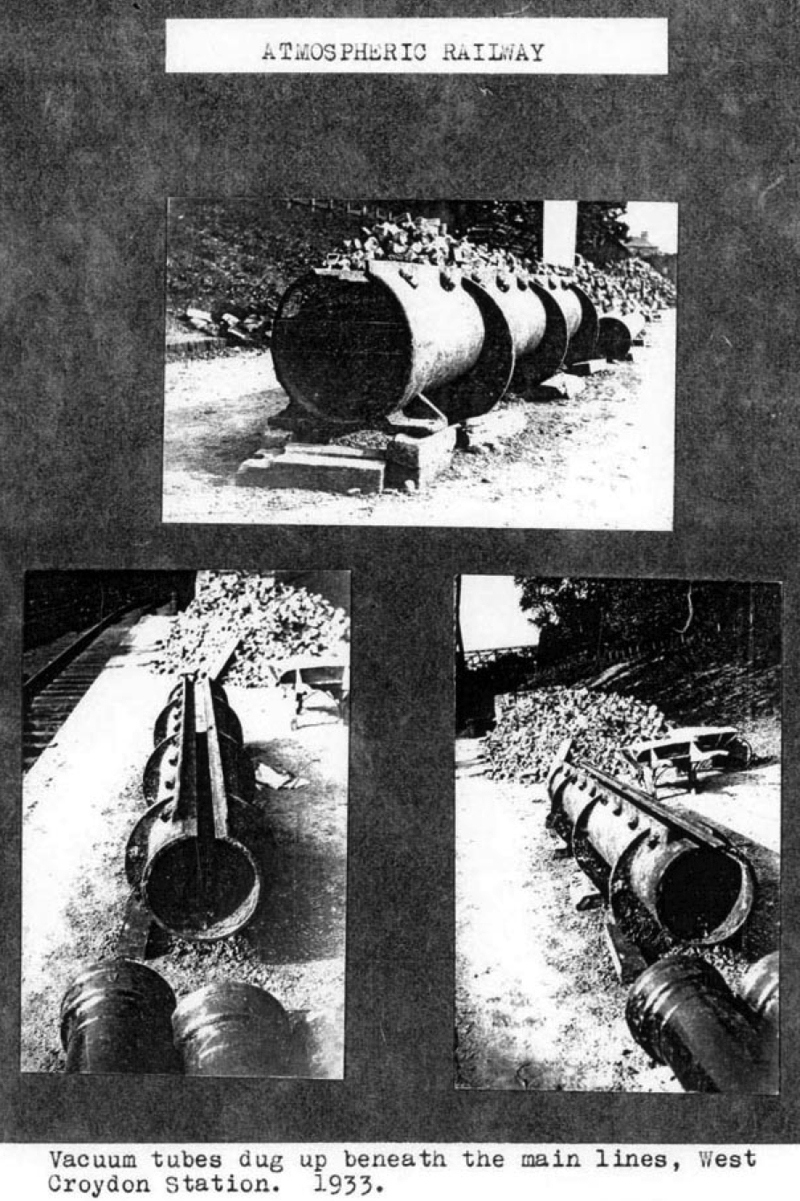

Of course it was too good to be true. The old man didn't know this, and neither did I, but the Croydon Library had in its archives the background to this piece of pipe.

— Croydon Library, via Paul Smith, "Le Chemins de fer

atmosphériques", In Situ, 2009.

All three of those pictures are of the same atmospheric pipe, and it is the one in the museum. The leather was long gone in 1933.

I guess the smaller pipes were not kept. By 1933 they were probably the last of their kind. I think they constituted the only record of how atmospheric trains were started out of Croydon. The method, documented in use later on the South Devon Railway, involved a piston in an eight inch pipe, trailing a long rope, the end of which was temporarily attached to the piston carriage at the front of the train. Vacuum created ahead of the piston caused it to pull the train forward until it had enough momentum to reach the main pipe, at which time the driver would release the rope.

I made some inquiries about the pipe on display, and received very kind responses from the National Railway Museum (York) and the Science Museum (London). This pipe was acquired by the Science Museum in 1933, object 1933-519, as a gift from the Southern Railway. It seems that the leather and the iron cover were manufactured and added for purposes of display in the museum. Clayton (published in 1966) mentions that this pipe and another from the South Devon Railway were both on exhibit in the museum in London. The pipe was transferred in 1998 to the National Railway Museum, a part of the Science Museum group, but it was never displayed there. At a more recent date it was loaned to the Museum of Croydon.

The year 1933 obviously coincides with the replacement of West Croydon station, but where was this pipe found? I mentioned earlier that the pipe must not have extended much beyond the engine house. The base map of 1898 does show platforms extending as far north as that. The lower left photograph above shows the pipe near the edge of a platform, and the other two show sloping ground on the other side, so it might be at the north end of platform 4. Only one section of atmospheric pipe is shown, as if no others were found.

This might not be the last remains in existence of the London and Croydon atmospheric railway. Hadfield writes:

The valve leather was offered in Northampton, and realized £8 per ton, presumably finishing up as boots. The tubes were disposed of in various lots, but some were used to underpin a slipping embankment on the down side at Haywards Heath, where presumably they still are.

It would be great to identify a pair of shoes as atmospheric leather.

There is a story that the Croydon engine house was taken apart and rebuilt as the first part of the Surrey Street water works. Because of the rapid growth of population in Croydon around that time, it was one of the first towns to establish a Board of Health. As one of their duties the board saw to the construction of a reservoir, pipes for water supply, and a pumping station. The first part of the latter with the date 1851 clearly marked is shown in my photograph below.

The date is reasonably near the end of atmospheric working in 1847. However I can see no detail of the building that looks the same as the atmospheric railway engine house, shown in the detailed drawing earlier on this page, except possiby the narrow window near the roof. But the engines were up for sale, and they were almost new. The assessment by Historic England credits the two engines as the purchase from the railway. The interior of the water works has been gutted, but the owner, Thames Water Utilities, is looking to lease it or even sell it, and the Croydon government would like to see it put to good use, so I think the building has a future.

The engines for the Epsom extension were built but not delivered when the London and Croydon arranged payment to cancel the contract. Clayton records that two pairs went to the South Devon Railway (which I will describe on later pages), one pair to the London and North Western Railway's works at Crewe, and the fourth pair to a non-railway company. The large pair from New Cross, installed but not used, also went to the South Devon Railway, specifically to the Dainton engine house, where they were once again never used. Clayton's book has a large amount of detail about the engines and pumps and I recommend it for those interested.

PISTON CARRIAGES

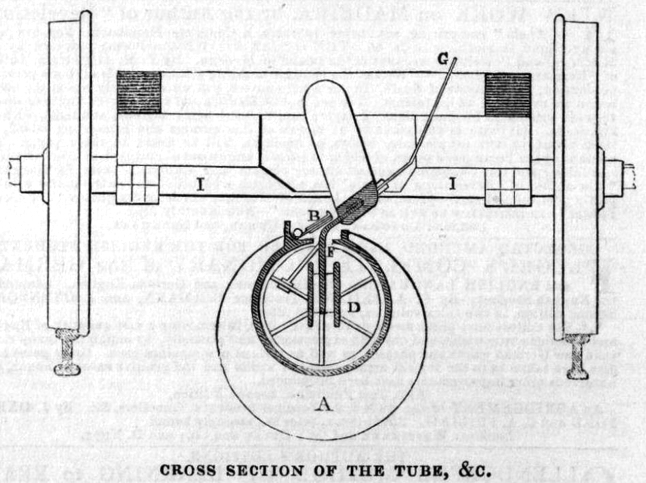

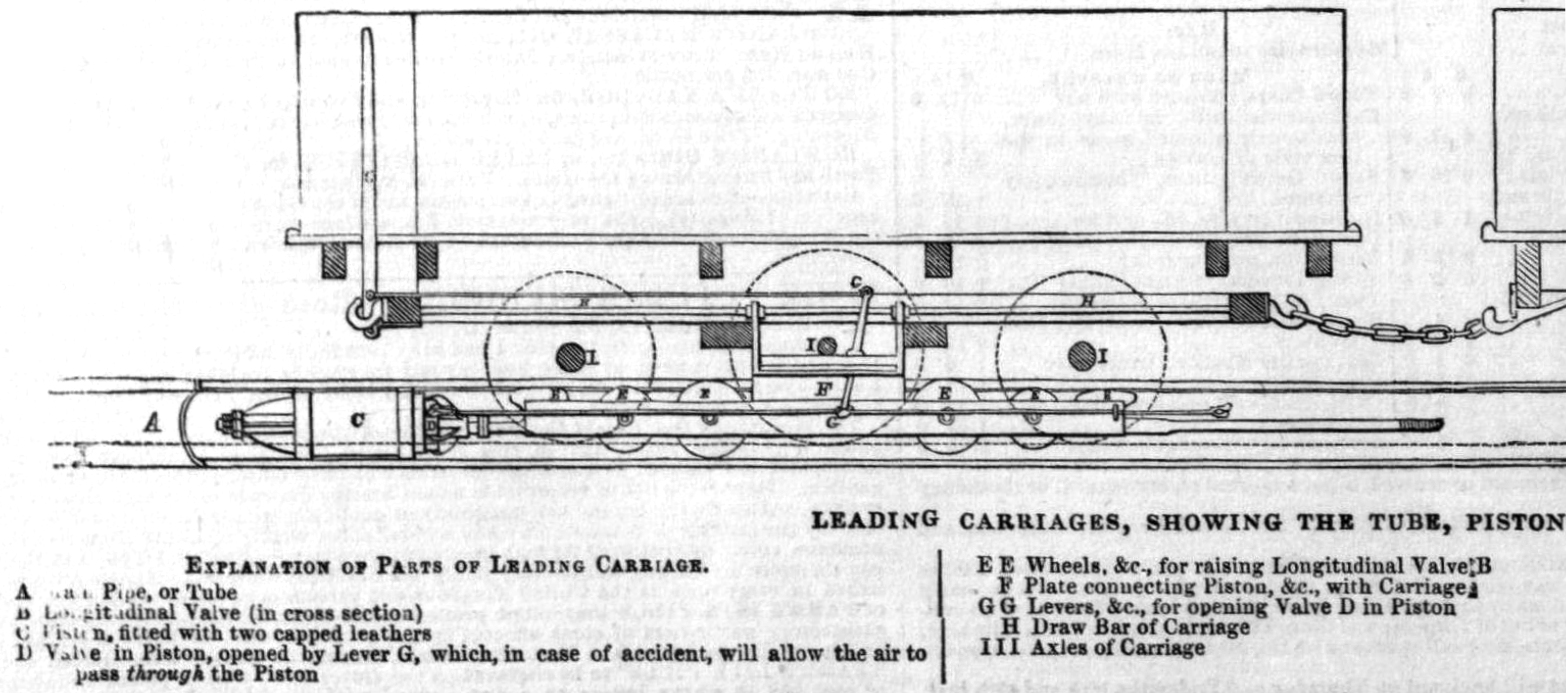

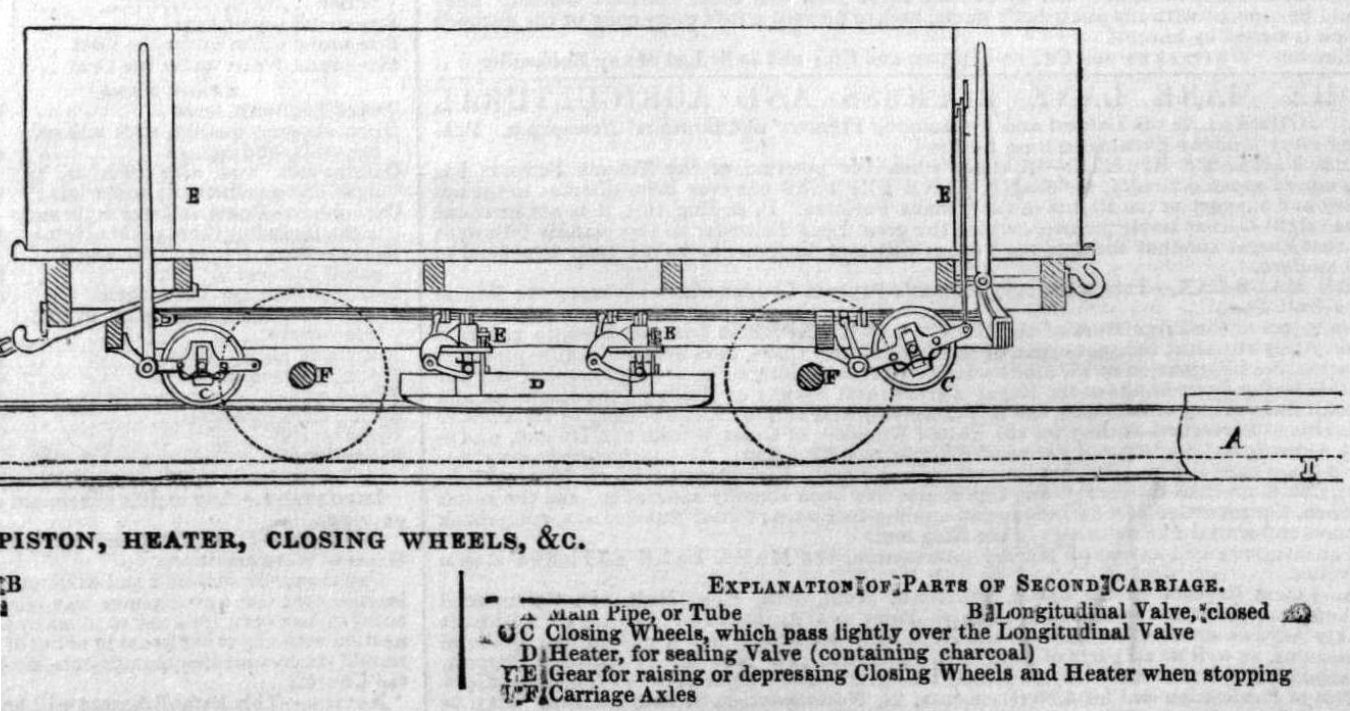

The mysterious open piston carriages in both drawings of the flyover are most likely based on plans supplied by Samuda before the Croydon line opened. Whether this type was actually used is not known. The following three detailed drawings appeared in the same issue of the Illustrated London News as the flyover picture.

— Illustrated London News, 11 October 1845. (all three above).

The letter labels are nearly the same for all three drawings. Here there are two piston carriages. The second one has the heater to soften the unctuous substance in order to seal the valve, and closing wheels to push down the valve cover. It looks as if it is bidirectional. But the first carriage seems not to be. The lever G to open the piston for intermediate stops is shown at only one end. It may be that for clarity the same equipment on the other side is omitted.

The piston is shown extending farther forward than the car body. Hadfield believes that it did so also on the double-ended piston carriages, making it a little easier to exchange the piston and counter weight at the end of each run, with no need to crawl under. A nice detail is that the piston is "fitted with two capped leathers".

Clayton mentions a detail that may help us figure out how they turned trains, namely that "a return of rolling stock made to Board of Trade in 1846, by Mr Young, the Company Secretary, lists six piston-carriages and four heater carriages." Six— for a railway that could run only one atmospheric train at a time! I had assumed that the piston carriage that brought a train in would be used to take the next service out, but the overabundance makes me believe otherwise. So does the use of heater carriages, which would have to be moved to the other end of the piston carriage.

The routine at the end of the line must have been something like this: disconnect the piston carriage and heater carriage from the passenger cars and move them forward; disconnect the two from each other and move the piston carriage out of the pipe; unfasten the piston and counter weight and reattach them at the opposite ends; move the piston carriage to another track take it back past the heater carriage; move the piston carriage onto the same track as the heater carriage and reconnect them; and attach a new set of passenger cars, either off a locomotive train (Forest Hill) or at the end of track (Croydon). All this would take some time, but if another pair of piston and heater carriages was waiting to take the next train out, then plenty of time was available.

Obviously using locomotives would be simpler.