Extra

Museum Pipes

In which Joe visits the musea that have atmospheric pipes.

The previous pages have concentrated mainly on engine house sites, which are almost all that can be seen today. The viaduct and tunnel of the Saint-Germain railway are impressive but they are not uniquely atmospheric railway works, nor are the numerous tunnels and fills on the South Devon. Those works of engineering fulfill their purposes today as well as they would for any type of railway. Unlike the handful of early locomotives on exhibit here and there, no piston carriages have survived. Beyond the engine houses, the only other specifically atmospheric remnants that you can visit are sections of atmospheric pipe, of which several examples can be found.

All of the pipes were manufactured in ten-foot sections. They were actually ten feet six inches in length, the extra distance being the socket into which the next pipe was fitted. Each pipe had three ribs along its length to help maintain the width of the slot. The diameter given for the pipes is that of the interior opening.

Manufacture was a precision job, especially the interior, since it had to be at all times smooth and just slightly larger than the piston. Nothing I have read mentions special sections for curves, but the brittle nature of cast iron does not lend itself to being bent on site in the way that rails are laid on curves, and neither does the tubular form. The many descriptions of the very smooth running under atmospheric power suggest but do not prove that there were many special castings, rather than a series of straight pipes with slight but abrupt changes of direction at each joint. At any rate all of the existing pipes are straight.

DALKEY (1844–1854)

No sections of Dalkey pipe are known to exist.

CROYDON (1846–1847)

One complete ten-foot section of 15-inch pipe is in the Museum of Croydon, and I described and illustrated it on the Croydon page. It was not preserved when atmospheric operation ended, but seems to have been left nearly in situ in dirt fill, because it was uncovered in 1933 at West Croydon when the station was being rebuilt. It was given to the Science Museum, and was on view in the museum in London for many years along with a section of South Devon pipe (see below). It is on loan to the Museum of Croydon, about a half mile from where it was found. It was probably during its time at the Science Museum that accurate recreations of the leather valve and iron cover were added to it.

The Croydon pipe may be the only one in existence that was once used to run atmospheric trains. My only doubt is that it might have been a spare part that had been kept on hand in the maintenance shop, because that might explain why it was not picked up in 1847 with all the others.

Charles Hadfield reports in 1967, source unknown, that some pipes "were used to underpin a slipping embankment on the down side at Haywards Heath, where presumably they still are." Those pipes were probably used to run trains. I wonder what condition iron pipes would be in after being in the ground for so long.

The photographs from 1933 also show what appear to be eight-inch pipes for the starting rope. If so they were the only ones of their kind known to exist as late as that date. It seems that they were discarded, since the Science Museum inventory has note only of the donation of the 15-inch pipe.

SAINT-GERMAIN (1847–1860)

No sections of Saint-Germain pipe are known to exist. At 25 inches it was the largest pipe used on any of the atmospherics.

SOUTH DEVON (1847–1848)

No sections of the 15-inch pipe used in atmospheric service between Exeter and Newton are known to exist, but a few museums give visitors a look at the 22-inch pipe that was intended for the grades beyond Newton Abbot, and installed as far as Totnes but never used. I was able to visit all but one of these relics.

The survival of some 22-inch pipes goes back to construction of the Dartmouth and Torbay Railway in the late 1850s, which extended the Torquay branch. Not far past Paignton it had to cross marshy ground at Goodrington, and to provide drainage, someone at the railway offices decided to use lengths of atmospheric pipe that were still in the South Devon Railway's inventory. Surplus bridge rail (described below) was welded upside down into the longitudinal valve slot to close it. The photograph below shows one of the drains as seen in 1912.

— Great Western Railway Magazine, May 1912, via the Atmospheric Pipes Project web site.

Let's visit the South Devon pipes, the longest first.

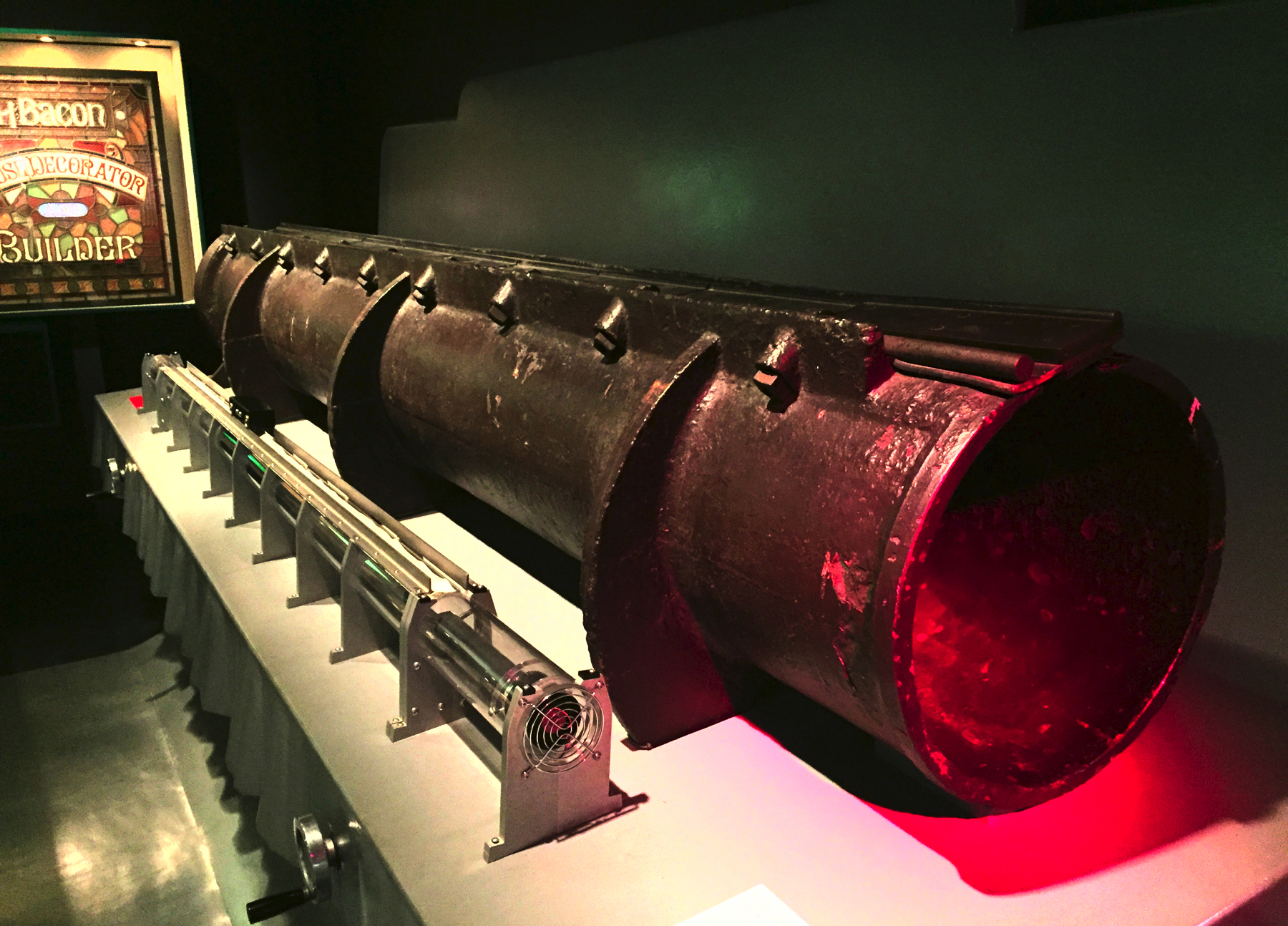

Didcot

Didcot Railway Centre has thirty feet of atmospheric pipe, by far the longest on view anywhere, three ten-foot sections fitted together. As recounted here an Atmospheric Pipes Project was formed in 1993 when members of the Great Western Society observed at Goodrington Sands the removal of drainage pipes that had a slot along the top. The society arranged to take away three ten-foot sections. At Didcot volunteers put in years of work to clean the sludge and stabilize the iron, and then assemble the exhibit, completing the task in May 2000.

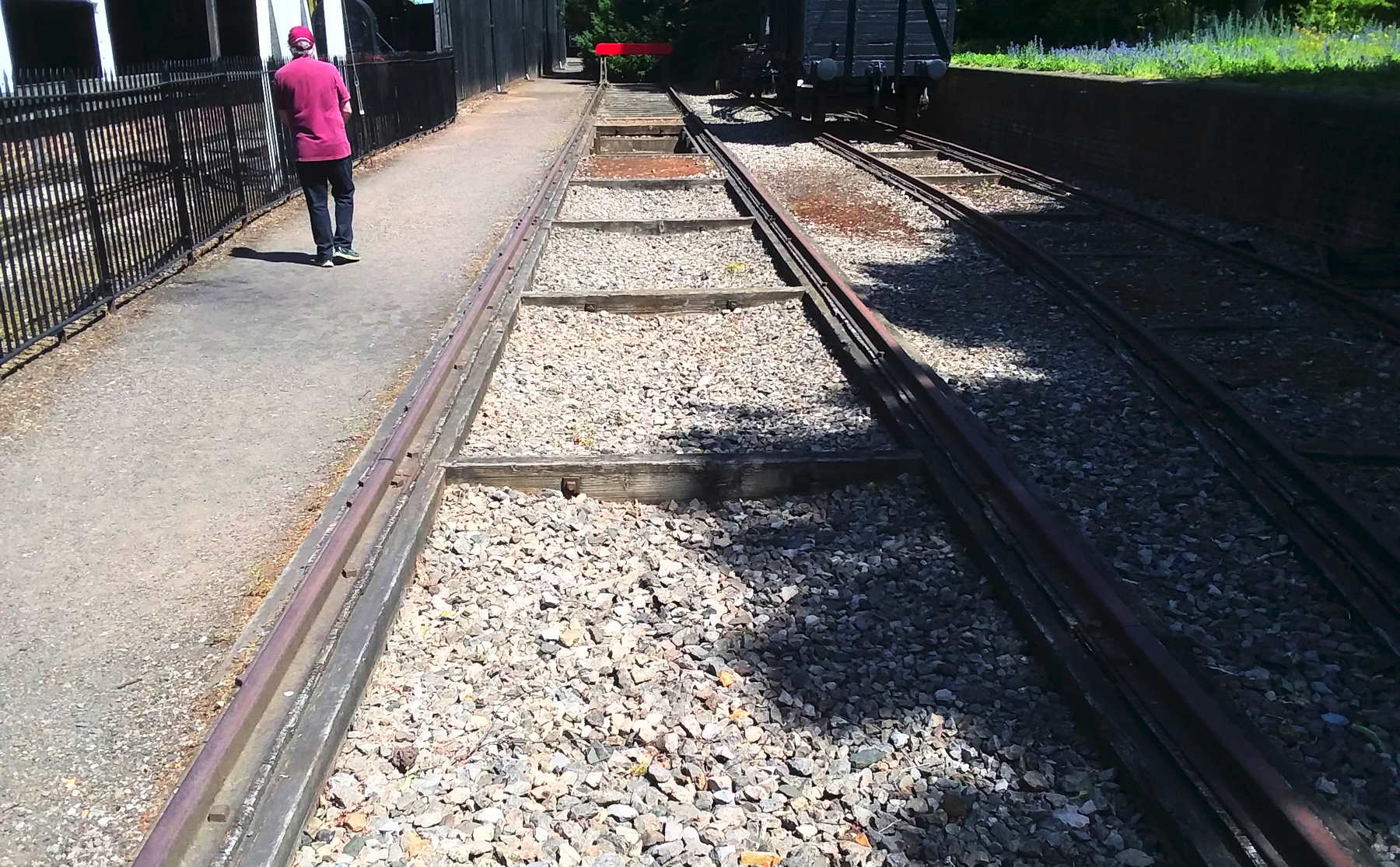

The pipe is appropriately exhibited with the type of broad-gauge track that was laid on the South Devon and other Great Western lines. Known as baulk road, it has relatively unusual bridge rail mounted on thick wooden baulks (beams), which are connected by wooden transoms to maintain gauge. For the atmospheric railway, the transoms were placed ten feet apart, farther than usual, in order to support the ends of the pipe. Not trusting the brittleness of iron rails, I.K. Brunel thought baulk road would give stronger and more reliable support under the weight of trains, particularly large broad-gauge locomotives. Baulk road was unusual on the "narrow gauge" (as Brunel called it) of other systems.

Above, the author walks next to broad-gauge baulk road at Didcot Railway Centre.

Let's now examine the three sections.

The wide socket end. Notice the transom, almost buried in the autumn leaves, and the mount cast into the iron. The bridge rail is spiked on alternate sides every few feet. We'll walk around on the path to the right.

A closer view of the socket end. The corrosion on the pipe is evident in all these pictures. It would have been smooth in original condition.

While the longitudinal valve slot was reopened during the restoration work, damage from welding it shut and corrosion make it hard to say now which side had the hinge, but it might be the far side.

The first pipe (left) is set into the socket of the second. A nearly hidden transom holds up the end of the second pipe. Compare to the previous picture. For purposes of the exhibit an additional thicker transom holds up the end of the first pipe, so that the corroded socket does not carry all the weight.

The second pipe (left) is set into the third, with the same extra transom supporting the non-socket end.

The non-socket end of the third pipe is broken off at the third rib, so not much more than a foot is missing. The extra transoms supporting its end and those of the other two pipes stand out very clearly from this point of view. They were not present on the working railway.

This is the best image I have of the bridge rail. It has a wide base for stability, which rests on a thin layer of wood that rests in turn on the thick baulk. The top of the rail is somewhat rounded. These are original Great Western bridge rails salvaged from a place that I was told but have forgotten.

The semaphore in the background controls one of the tracks used to run trains within the railway centre's property.

Just for fun, below is a look down the bore from the socket end. Nice and straight.

Bristol

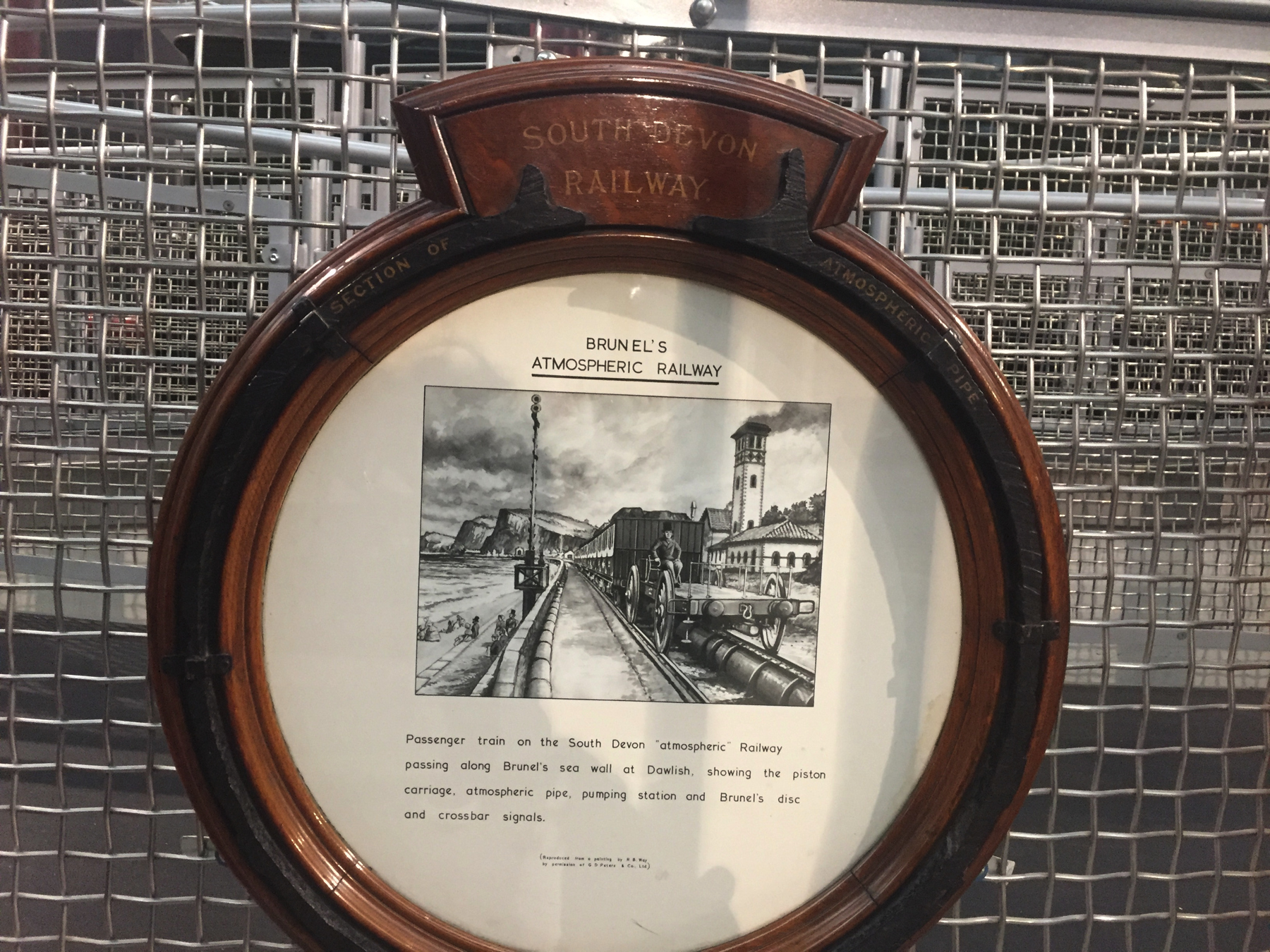

The museum called Brunel's SS Great Britain is of course concerned primarily with exhibition of the ship of that name, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, but in 2018 the museum added a new section, an entire building dedicated to his life and works, under the name Being Brunel. The museum within a museum draws attention to many things Brunel worked on, among which is of course the atmospheric railway.

In 1912 the Great Western Railway Magazine ran an article about the South Devon that mentioned the atmospheric operation and included the picture I have already included on this page of the drain pipe at Goodrington. The next year the magazine reported that the GWR had transported some pipe, from a source not stated, to London. One of the items was a full ten-foot section of 22-inch pipe that was given to the Science Museum in London, and it was this that was exhibited for many years alongside the 15-inch Croydon pipe. Howard Clayton, writing in 1966, mentioned seeing it. Later on this section was taken off exhibit and stored at York in the National Railway Museum (part of the Science Museum). It was loaned to the Starcross museum, and then taken back to York, and now it has appeared again at Bristol.

This pipe is in much better condition than that at Didcot and shows no sign of the slot having been welded shut, as if it is not from Goodrington, although why it would have been still in storage in 1913 is a wonder. The display at Being Brunel includes bridge rail, but the transoms are not located correctly, and most excruciatingly bad, the trompe l'oeil painting that continues the track very nicely is ruined by the appearance of the silly flatcar piston carriage, which I decline to show here.

Swindon

In Swindon, STEAM, the Museum of the Great Western Railway, is located in buildings that were part of the Great Western Railway's repair and maintenance works for more than a hundred years. When the GWR offered a ten-foot section to the Science Museum, the company also retained a much shorter sub-section for their own museum in Paddington. This seems to be the piece that is now on exhibit at STEAM.

The silhouette in the frame in the first picture suggest that it might have been installed at an earlier date on the end of the subsection of pipe. The picture is properly credited to R.B. Way but does not give the elusive date of its publication. It certainly does not date to 1912.

Newton Abbot

The Newton Abbot Town & GWR Museum has in it a GWR Room that includes another sub-section of pipe similar in length to that in the STEAM museum. I was not able to visit this one because in 2018 and 2019 the museum was closed, its exhibits packed up for a move to a new location in a former church now called Newton's Place in the Town Centre, which opened in October 2020. The provenance of this pipe is unknown to me, but my guess is that it dates to the 1912 gifts. Newton Abbot was the center of operations of the South Devon part of the larger Great Western network, and its museum was worthy of a relic.