South Devon Railway

Starcross

In which Joe finds an atmospheric engine house at last, and a secret underground chamber.

Explorations: 26 June and 11 October 2018, and 28 June 2019.

Journeys: Paddington to Exeter St Davids, and St Davids to Starcross, or

St Davids to Exmouth and Exmouth to Starcross.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Paul Garnsworthy, editor, Brunel's Atmospheric Railway, The Broad Gauge Society, 2013.

- Peter Kay, Exeter–Newton Abbot: a Railway History, Platform 5, 1991, and excerpts in Garnsworthy.

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- G.A. Sekon, A History of the Great Western Railway, Digby, Long, 1895.

The fourth engine house is the first one after Exeter that was close to a station. The building has survived almost intact.

Before the railway Starcross was small village known for cockles and oysters that was becoming a "watering place" for people who preferred holidays at waters more protected than the English Channel. It had a ferry across the river to Exmouth, and a quay at which some ships landed to transfer freight to smaller boats for Exeter. The buildings were lined up along a street called the Strand. The railway was built on made ground off shore, its tracks and stone embankment cutting off almost all access to the water. Half the old quay was left inland, and some houses along the shore had to be demolished. The village almost stopped growing. Many buildings that existed along the Strand in the 1840s are still in place.

— Starcross station and engine house, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1890. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan.

The South Devon Railway opened as far as Teignmouth on 30 May 1846, using two locomotives rented from the Great Western Railway. It was a single 7 foot ¼ inch broad gauge track. At Starcross and Dawlish a second loop track diverged to the land side and ran alongside a station platform under a trainshed roof, while the main track ran straight past, outside. Brunel's proposed construction had a platform on both sides, but until after the atmospheric period no platform was built for the main track, which was rarely used at all, since no regularly scheduled trains passed in opposite directions. The OS map shows the wider trainshed of 1848 that covered the newly built down platform too. The station house of 1846 was a quickly built simple wooden building that was supposed to be temporary. The 1848 trainshed was taken down in 1906 to make way for renovations that never came, and in 1981 what was left of the 135-year-old temporary station house was simply removed. In its place are public toilets, and a building occupied by a fast food vendor.

Construction of the Starcross engine house began in August 1845, two months after the first three. Like Turf, it was subject to a late change of plan by Brunel, in this case to have the north wall placed 30 feet from the Courtenay Arms Hotel instead of 15. The buildings stand on mud, and because it began to tilt, the chimney soon had to be taken down built over again on piles and made "thinner and lighter". Nonetheless in January 1846 the same problem recurred and it had to be taken down again and rebuilt. In his book Peter Kay calls attention to the small openings to let in daylight, which none of the other chimneys have, and wonders whether it is the only one with an internal staircase. He says that it still has "bad lean", but I can't detact it.

This was the first engine house for which SDR track could be used to bring in construction material. The siding was placed on the north side of the Courtenay Arms. Afterwards the same location was used for the coal siding, even though it was inconveniently sited away from the boiler house. At the south end of the up platform there is still a stone mound protecting the hotel from the long-gone siding.

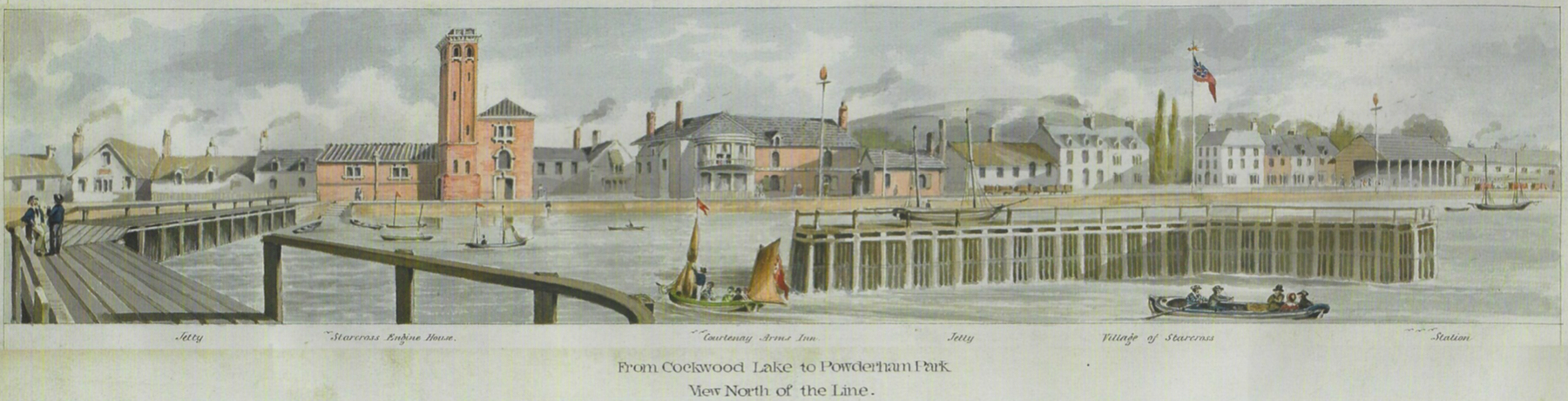

For Starcross William Dawson provides a view from out on the pier. In the right foreground is the breakwater that protected the harbor. At left center is the engine house. The next large building to the right is the Courtenay Arms (named for the Earl of Devon's family), with a white rounded balcony and a brick main house. The space between this and the engine house is exaggerated. To the right is the siding with coal wagons, and farther on is Starcross station with its train shed open on the water side.

— William Dawson, "From Cockwood Lake to Powderham Park. View North of the Line." via Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

A piston car was towed to Starcross on 11 March 1847, a week after the tests to Turf began, but the engines were not started until 23 March.

I mentioned that the station platform was on a loop track off the main line. The coal siding then came off the loop. The platform was 280 feet long, but the total length of the loop track was probably twice that. Normally all this is nothing to remark on, but on an atmospheric railway, which cannot pass over points, some 600 feet is a very long distance without any propulsion. It is especially so when there is a station within that length. How did trains start, without the pipe?

The solution used at Starcross and Dawlish was starting ropes like those I described at Croydon. A piston was placed in the end of an 8-inch pipe, with a rope that could be hooked to the front of the stopped train. Vacuum created ahead of the piston drew it forward and it pulled the train until it gained speed. Near the points the driver would drop the rope, which woud fly forward into the pipe, and the train would coast into the main 15-inch pipe and be on its way. Station staff would pull the rope back out in order to repeat the performance with the next train.

The starting rope caused at least two accidents at Starcross. On 9 November 1847, the the rope broke and snapped like a whip, knocking down a porter who died from head injuries. On 4 March 1848 porters left the rope lying on the track, where it derailed a piston carriage (presumably coming in the opposite direction from the train the rope had started). Hadfield adds that the station manager was then directed to put a guide bar on the platform to show where the rope should be placed. But after this Brunel was asked to implement a different design altogerher, a short 15-inch pipe within the space between points, so that trains, between coasting over the points, could run in a normal way with the piston in the pipe.

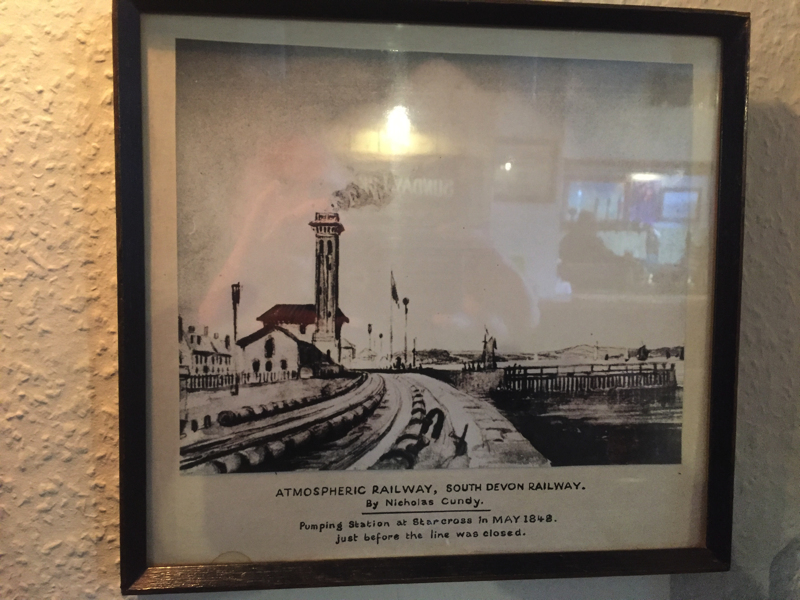

Nicholas Condy (the elder) was a painter who lived at Plymouth. He painted two scenes of the atmospheric railway of which the Dawlish painting is the better known. I learned of the Starcross one only when I found a crude black and white reproduction framed on the wall inside The Atmospheric Railway pub. The caption date of May 1848 is not correct (see below), nor is the spelling Cundy.

— Nicholas Condy, view of Starcross, via The Atmospheric.

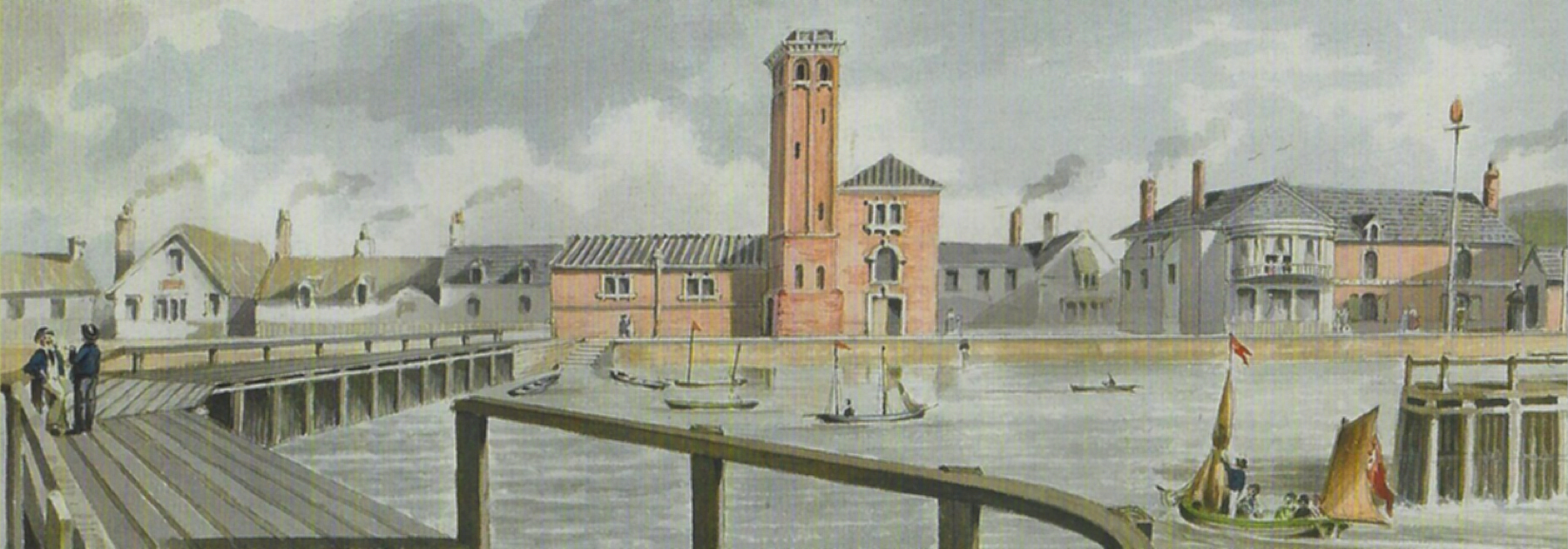

I was able to secure a better version, below, which shows it to be an unfinished work. Pencil lines show through and the sky has none of the wonderful clouds Condy liked to paint.

— Nicholas Condy, view of Starcross. Ironbridge Gorge Museum.

We are looking north. At the left we see a small cabinet, mostly in pencil, within the open space over the water tank, with a tall post that seems to be, like others in the distance, a telegraph standard. Beyond is the boiler house with a small shed next to it. Just farther back are the chimney and the engine house proper. On the ground, on the left is the 8-inch pipe for the starter rope (for down trains), the broad gauge track with a 15-inch pipe with the valve along the top. To the right is 15-inch pipe without a valve and with a U-shaped device attached. In pencil Condy sketched another track on the sea wall that is not otherwise documented. There was a siding on the old quay but Peter Kay's best documentation has it ending there. In the distance a sketch of the station trainshed is painted yellow.

Condy's view is of an earlier date than Dawson's, because it does not show the pier, only the old quay (under the orange sail) and the breakwater that is farther away. Peter Kay's book dates the pier construction by the South Devon Railway after the board meeting in August 1846. Condy must have visited earier in 1846, since he does have the engine house building complete and accurate.

The Starcross engine house today

We arrive from Exeter by train. First we look back north. This is low tide. The water can come up to the wall, but it will still be very shallow. The railway was built on new ground where high tide had once reached. The street next to the railway, called The Strand, was literally that, the top of the original coast line. With the coming of the railway small boats could no longer be pulled ashore.

Below, we look across the Exe, toward Exmouth, then and now a much more populated place than Starcross. What I mark as "low pier" on the OS map is perhaps more of a plank walk across the mud to reach slightly deeper water. On the right side is the masonry breakwater that succeeded the wooden one in the old pictures, and obscured past that is the main pier, which we will see more of below.

And next we look south toward our departing train and the engine house. The footbridge and the shelter back there on the up side is almost all there is besides the platforms. From the town, you get to the pier by walking over the station footbridge and then past the end of the down platform.

Our interest of course is the engine house beyond the station. Follow signs to the pier, and you can go out a short way even when the pier is closed. Look back and the whole building is in view. Dawson's view is a very good match, except that the top of the chimney is now gone. Even Peter Kay's research has not established the date, but the top is already gone in a photograph from the 1920s. He believes that it was removed to reduce stress from the chimney's lean toward the engine house. The fence keeps us off the railway. The building to the right is the Courtenay Arms.

A closer look at the boiler house. The red stone has weathered badly over the years. It looks like the Heavitree breccia we saw in Exeter (see the Exeter St Davids page), but Kay suggests that the source might be the quantity of stone removed for the numerous open cuts and tunnels around Dawlish, which were under construction around the same time the engine houses were built. See also the red mud at Starcross. By contrast the Bath Stone (a limestone) around the windows and doors has aged well. The circular cuttings under the window sills are still sharp. The metal near the track, on the left side, is the top of a tunnel crossing under, a slipway provided in partial compensation for blocking off most access to the water.

Turning to the right, we see the chimney and the engine house proper. The arches over the lower chimney windows are of the red stone. The narrow windows farther up have no more than little rounded tops cut into the single stone above each one. I do not know the purpose of the vertical metal strip. (The movement of the flying bird caused a peculiar artifact in the photograph.)

Notice the whistle sign for up trains. From 1861 to 1972 there was a footpath level crossing in the space north of the engine house, for people to reach the pier. It was extremely dangerous because the curve was enough to hide from view approaching up trains. For this reason they were required to whistle. There must have been another whistle sign farther away too.

Moving along to the north, on a sunnier day, we can see the more elaborate Bath Stone accents on the engine house. It's all a little bit nicer than the boiler house, possibly because it is more visible from the street and the Courtenay Arms. Peter Kay mentions that the stone corbels (under the edge of the roof) were designed by Brunel based on a visit to Italy. The one opening with only red stone is the large arch at ground level, through which only workmen would go.

It's quite a walk to the street side: back to the station, over the footbridge, and then along The Strand, which is only one lane wide as it passes the engine house. I notice that the large arch had a rich blue door in 2018. Up on the first story, it is more clear here that there is an alcove between the pair of windows. I wonder whether Brunel planned to install a statue in it. The symmetry is striking, along this north side but also the matching sea and land ends. The door to the street was created in 1869. It has not even a simple stone lintel.

This next picture is pretty similar, but I wanted to give a closer view of what happened to the street side of the boiler house. On Wikipedia there is a photograph from June 2007 that shows the original stone along The Strand. But sometime in the next eleven years it was re-surfaced. Maybe bits of the red stone were breaking off into the street. The Bath Stone was kept in place.

The other thing here was an opportunity missed. See the work site at the extreme right? I thought it was nothing. But it was researchers from the Wessex Archaeology organization, who were on site in 2018 to document the underground water tank for the engine house! It was discovered by surprise during work on flood defenses. While removing the pavement of a parking lot the crew uncovered a round opening to a deep dark space below. The authorities were notified.

Because the engine house itself is Grade I listed (the highest grade), the associated reservoir is considered part of that listing. I wonder, if I had gone up to the fence around the work, could I have grabbed an image of the three-foot wide hole?

Here are a couple of details of the engine house, showing the weathering of the red stone and the contrasting Bath Stone.

Here are all three parts of the building, seen from the narrow street.

The south side of the boiler house has been altered. You can see in the Condy painting that there were three arched openings at ground level and a tall center window in the upper story. Peter Kay reports that the large arch was opened in 1858 to provide entry for a railway siding, when the building was in use by a coal business, which closed in 1899. I suppose the arch on the left is original, but the Bath stone arch within a larger red stone arch is peculiar. The whole wall has been repointed at some relatively recent date but at least the stone is intact.

This second view is better except for the ferry company van blocking the arched door. I'm including it also because you can see where the slipway is. The Starcross Fishing and Cruising Club may be using it.

Did I ask, could I have grabbed an image of the three-foot wide hole? The photograph below from the Wessex Archaeology report makes me think so. By now the hole has been covered up again, so I supply this image to document where it is.

— "Tripod setup over current opening." from B. Davis, Underground Reservoirs at Starcross Pumping House, Wessex Archaeology, 2018. CC BY 4.0

The reservoir was found to be in two parallel arched stone masonry chambers connected by numerous arched openings, each chamber about 14 feet wide, 106 feet long, and 6 feet high to the top of the arch. There was about 3 feet of water inside. The hole is at the north end of the east chamber.

From the report: "The restricted access meant that all photography was taken via a pole mounted camera in inverted orientation using flash photography. It was not possible to light the interior of the chamber. The presence of hanging salt stalactites interfered with focus." But the picture below is pretty good. In the photograph the water is almost to the top of the arches to the other chamber.

— "East chamber interior taken from north aperture. Tops of dividing wall arches visible to right above water level." from B. Davis, Underground Reservoirs at Starcross Pumping House, Wessex Archaeology, 2018. CC BY 4.0

Headline in the Dawlish Gazette of 26 May 2018: "Chamber of secrets sinks road plan." In addition to the proposed flood control barriers, the local council had also planned to widen The Strand. It's not going to happen.

The Starcross – Exmouth Ferry

The ferry at this location goes a very long way back. Peter Kay gives a date of 1267 but that may not be the start. The agreement under which the Earl of Devon sold property to the South Devon Railway in 1844 required the SDR to build a landing place for the ferry. The SDR went further, acquiring the ferry rights in 1845, but the company leased operations to others. The pier was built in 1846, but in an inconvenient location if the ferry and railway were supposed to connect, which was to be expected since Exmouth was a large town that would provide many more passengers than Starcross. There was some talk about building a "permanent" Starcross station on the south side of the engine house (over the water tank), and that was where the pier was placed. Passengers from SDR trains had to walk out of the station, and down The Strand and then cross the tracks to reach the pier. The direct path along the sea wall from the down platform was not supplied until 1899.

The SDR sold the ferry rights in 1869 and was not involved with it any further. The opening of the railway to Exmouth in 1861 had cut out much of the boat and train business between there and Exeter. Yet into the 1970s the ferry times were coordinated with train times and listed in the Great Western Railway timetables as if the ferry was a GWR service.

In 2019 I decided to take the train to Exmouth and cross on the ferry on my last trip to Starcross. (I was on my way to Babbacombe for the All the Funiculars series.)

Because of the shallows the ferry cannot go straight across, but has to run a little ways to the south before turning northwest. I took some pictures as Starcross came into view. In the first picture, on the left, is the General's Lane slipway under the railway. Harder to see, in the last of this series the slipway at the boiler house comes out to the left of the stone arch leading to the pier.

Now I walked the length of the pier. There is a small building where the path jogs to the left. I ended up with a view like that of Dawson, so I will supply a detail.

The pier is closed to the public when the ferry is not running. I think boat owners have the key. The slipway in front of the boiler house comes out right next to the stone part of the pier, the left side as in the first picture. The second picture shows the arch that would lead to it. The last view from the boat, above, shows the other side of the arch. I think it may be possible to use the stone steps, the arch, and the slipway to reach the street, but it is not marked.

Good-bye to the Starcross engine house. I saved the best picture.

Two last views of the station. Behind the shelter is Bonhay Road, and not far beyond that are hills and fields. And... yes I rode a Pacer from here to Torquay!

If you're writing about the Starcross site I think it's obligatory to include the sign of The Atmospheric Railway Inn, even if the graphic shows the buildings at Dawlish. They're pretty similar. The atmospheric train is not right, a matter I will come back to on a later page.

It was a real off hour when I went in, but the barkeep was able to get me a ham sandwich with chips and, what else, a pint of Brunel Bitter. The only other customers were two men with a dog. They threw a ball of cloth and the dog brought it back. I had two turns tossing the slobbery ball and the dog brought it back to them. If you go, look around at the pictures on the wall.

The later history of the Starcross engine house

After the end of atmospheric working in 1848, the building and equipment were offered for sale. The buyer of the Starcross engines did not come through on the deal, and they were finally sold a second time and removed in 1856. The boilers were sold and removed at an earlier date.

The earliest documented re-use was by a coal merchant who took a lease on the boiler house in 1858, the one who made the larger arch opening so that rail cars could come in. A series of fuel merchants continued the same kind of business, eventually those storing motor vehicles inside the large arch, until 1981.

The engine house became a Methodist chapel in 1869. A new floor was installed one story above street level, which was reached by stairs from the new street-side doorway. The Methodists left in the 1970s. Peter Kay reports that British Rail wanted to demolish after that, but the building was listed in 1979.

The entire site, from the engine house down to the lot over the water tank, was purchased in 1981 by Richard A. Forrester. He made much-needed repairs to the buildings, including roof replacement. In them he created the only atmospheric railway museum, called The Brunel Atmospheric Railway, which opened in 1982. Forrester had been collecting atmospheric papers, among which was a technical drawing called "Water Tank in connection with South Devon Atmoſpheric Railway Starcroſs". His widow Valerie told the Dawlish Gazette in 2018 that they knew about the tanks from the document and located them "using dowsing rods in the car park." The drawing was even on exhibit in the museum, but, she said, "Everyone who came was more interested in the pump house and what went on in there." I am sorry to say that the museum closed in 1990.

— Starcross museum, 1980s. © Alan Mazonowicz. Used by kind permission of David Cornforth at Exeter Memories.

The museum had a complete ten-foot section of atmospheric pipe. I think it was the unused 22-inch pipe given by the Great Western Railway to the Science Museum in London, and on exhibit there for many years. Howard Clayton (published in 1966) saw it there together with the London and Croydon 15-inch pipe. It would therefore have been on loan to the Starcross museum, and I think it is the pipe now on loan to the "Being Brunel" exhibit at the S.S. Great Britain museum in Bristol. I do not know what became of the rest of the Forrester collection.

The property was purchased in 1993 by the Starcross Fishing and Cruising Club, with the boiler house front as the primary entrance, just as it was for the museum. Their renovations were completed in 1997 with the Brunel Tower Clubhouse. They have a Brunel Tower Live Interactive Webcam.

NOTES

In my explorations in Britain I always preferred the train as much as possible, partly because the Britrailpass makes it "free" as in already paid for, for a period of time, and so I wanted to get my money's worth. In fact the Britrailpass is a savings only if you plan to do a large amount of train travel or need to decide on the spot which train to take. Both of those applied to me, but not everyone. No regrets here. Even with the pass, paying out a few pounds now and then for something like the Exmouth–Starcross ferry should not be avoided.

TODAY'S ETYMOLOGY

Now "star" and "cross" are ordinary English words, but what do they mean when put together? The question was asked in 2016 on the Starcross History Society web page, but no answer appeared. Two hundred years ago the place was sometimes spelled as two words, Star Cross, but that tells us little. St Paul's church in the village dates only to 1828 and that is the date of the parish itself. Cary's A New and Accurate Deſcription of all the Direct and Principal Croſs Roads, 1811, does mention Star Cross as 1½ miles after Powderham Castle, so the name predates the parish. Likewise Samuel Baldwin's A Survey of the Britiſh Cuſtoms; Containing the Rates of Merchandize, 1779, includes Starcross as one of very many ports.

We find in J.B. Davidson, "On the Ancient History of Exmouth" (Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, Literature, and Art for July 1883), that Pope Eugenius granted Sherborne Abbey certain privileges in 1146.

Amongst the other privileges conferred upon Sherborne Abbey by these grants was the right of the ferry from Exmouth to the opposite shore of the mouth of the river. The starting-place of this ferry was at a place called Pratteshide, which is spoken of by Dr Oliver as an ancient name of Exmouth. At any rate it was a place of resort for the purposes of the ferry, and of some commercial importance. [...] On the other side of the river the ferry terminated at a place formerly called Woolcomb's Island, where there was a flight of stone stairs; and near this ferry-house was set up by the bishop of Sherborne a stone cross, whence was derived the name Stair, now Starcross.This Dr Oliver goes on to say that the rights to the ferry were given to the "mayor and bailiffs of Exeter" in 1267, the year given by Peter Kay. Kay notices that the ferry had two western docks at various times, the other being the isolated place Warren Point, at what is now called Dawlish Warren, and which seems to me, because of the shifting sands, to be much more likely to have been an island at times than Starcross ever was. But neither there nor at Starcross was there any need for stairs decades before the sea walls were built.

I am not very sure about any of the foregoing.

The name is reminiscent of the star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet. I found no mention of the place Starcross before the date of the play, 1597. William Camden's Britain, or, a Chorographicall Deſcription (1610) skips from Teignmouth to Exeter. Was there some tragic event at Starcross? It is romantic to think so.