Chemin de fer de Paris à Saint-Germain

Le Pecq

In which Joe explores a country where the natives speak a foreign tongue, and finds himself admiring a gigantic viaduct built for an atmospheric railway and a gigantic illustration of the same, and concludes with remarks about a place in his home state.

Explorations: Wednesday, 10 October 2018, and Thursday, 10 October 2019.

Journey: Châtelet–Les Halles to Le Vésinet–Le Pecq,

RER A.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Paul Smith, "Chemins de fer atmosphériques", in In Situ,

no. 10 (2009), online:

première partie, and deuxième partie.

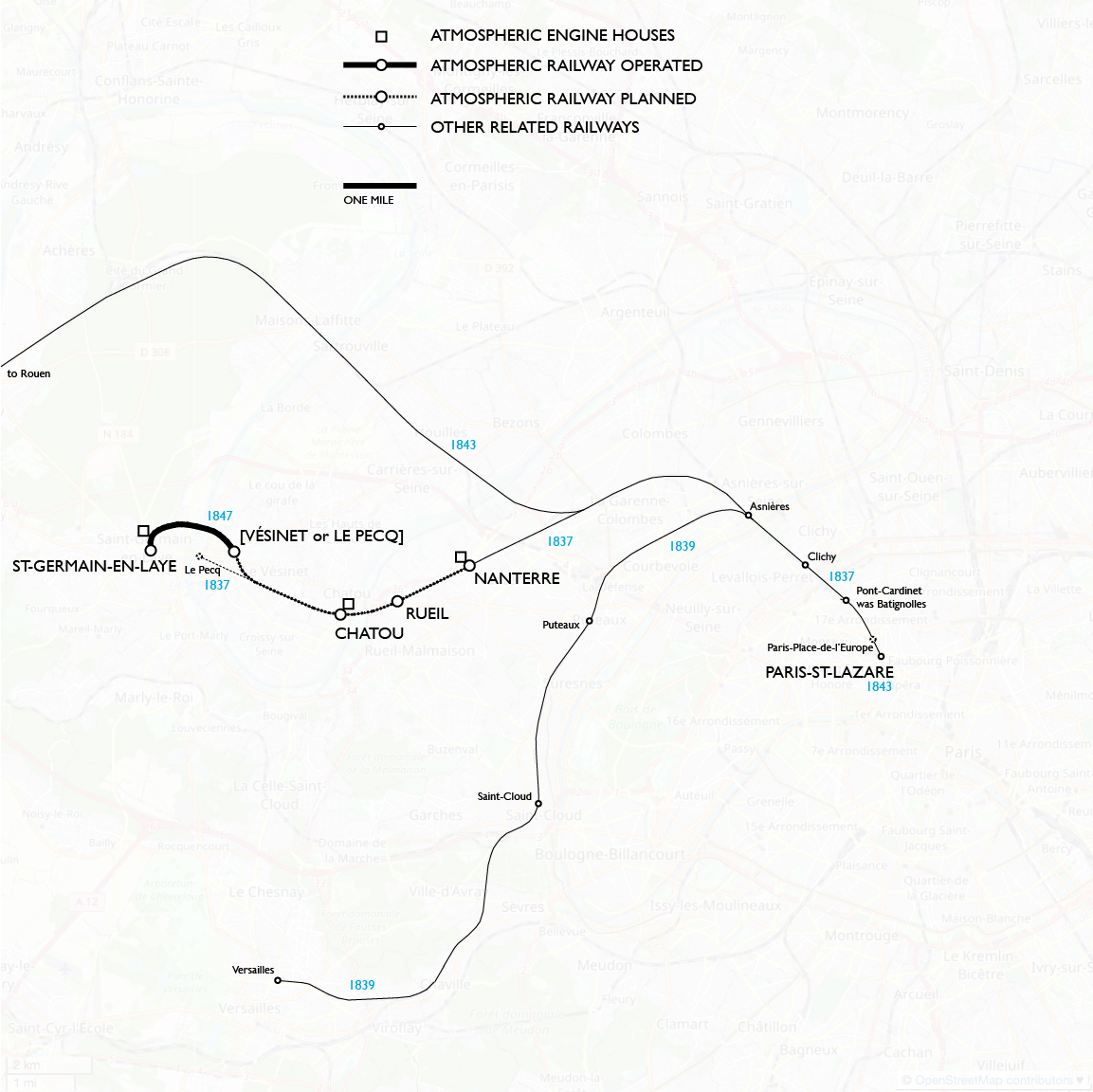

The third atmospheric railway was more like the Dalkey line than the Croydon, a short extension to an existing railway that surmounted a grade impossible to work with locomotives... so it was thought.

The Chemin de fer de Paris à Saint-Germain was the first railway from the French capital. The Pereire brothers, Émile and Isaac, a financial firm, obtained an Act to build it in 1835. One of the state's goals in promoting it was to demonstrate a railway to influential people in Paris and thereby promote investment in building more and longer railways throughout the country.

The Saint-Germain railway opened on 24 August 1837 to great acclaim. The popular writer Jules Janin wrote, in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, "Hier encore, aller à Saint-Germain, c'était un voyage ; aujourd'hui il ne s'agit plus que de sortir de sa maison." What was once a long journey was now only a matter of getting out of the house.

The route chosen was nearly level and through mostly open land, although it did require two bridges over the looping course of the Seine. The outstanding defect was that it did not go to Saint-Germain. The outer terminal was at a village called Le Pecq where there was a bridge across the river. Passengers for Saint-Germain walked over the bridge and up a very steep hill, or rode in a horse-drawn bus subsidized by the railway company. What was new was that the railway brought passengers from Paris in 25 or 30 minutes, not four hours by boat or carriage.

There was a small port business at Le Pecq because it was at the lower end of charges made on River Seine boat traffic by Parisian interests. For centuries some merchants chose to unload incoming freight here on the rive gauche side, and later when bridges had been built, some chose the "bridge route" that was similar to the path of the railway. I'm not sure how much freight the railway handled though. Everything I could find emphasized its superiority for passenger traffic, a market that is more sensitive to travel time.

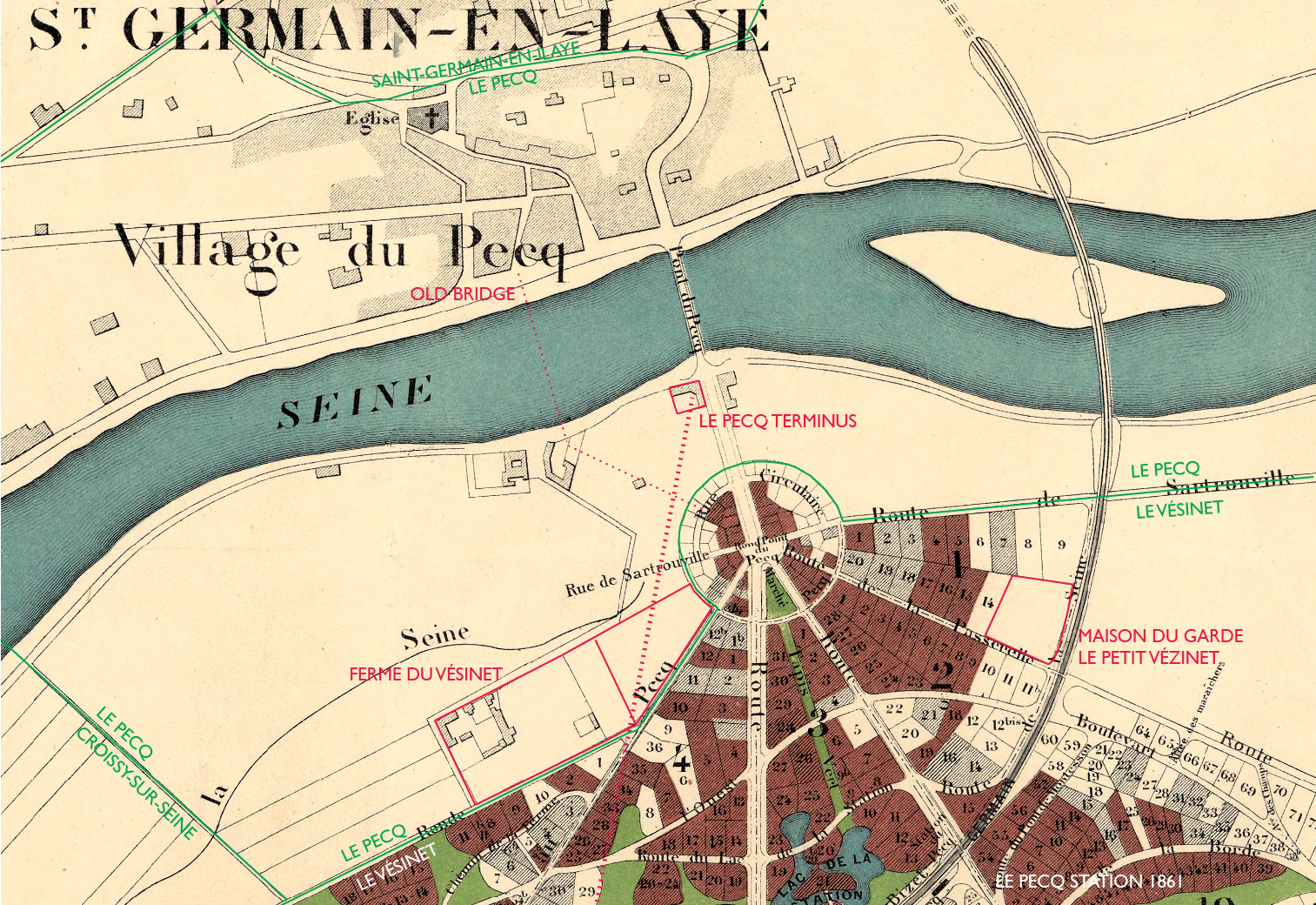

— E. G. Hubert,

Plan de le ville de St-Germain-en-Laye et de ses environs,

1840. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF.

The map above shows the Le Pecq terminal at far right. In the Légend its number 29 is described as Débarcadère du chemin de fer. The bus service went across the Pont du Pecq and up the winding Route de Paris, its grade beginning just across the bridge and reaching the plateau at Place Royale. Pedestrians could take the same route, or if they had courage there were steps they could take starting at the first big bend. The name Village du Pecq is shown here on the rive gauche. The older bridges crossed at the "E" at the end of "SEINE", connecting a main street of the village to a few buildings on the other side.

The destination for most visitors was the grounds of the Château (number 2) in the upper left quadrant. The Parterre is a formal symmetrical garden and the Quinconce is an arrangement of manicured trees in straight lines. The strong vertical up to Porte Dauphine (and extending much farther) is the Terrasse offering breathtaking views as far as Paris. All this is still there today although the layout of the pathways, gardens, and trees has been changed a few times over the years. In the church of Saint-Germain (number 1) is the tomb of the exiled James II of England and VII of Scotland.

Galignani's New Paris Guide, 1841, tells visitors about Le Pecq that "since it became the station of the rail-road, it has extended to the opposite side, whence the trains start". That was not correct, since Aupec had been on both banks for a thousand years, but for a long time the main population was in the cité neighborhood on the Saint-Germain side where there was good business supporting the wants of the royals and friends. There was nothing to interest visitors on the rive droit besides the railway station, so that's all we get on this map.

Samuel Clegg visited in 1839 and suggested to the Pereire brothers that the missing end of the line would be an ideal test bed for the atmospheric railway idea he was working on with the Samuda brothers, but they did not take the bait.

Reminiscent of the London and Greenwich Railway's obligations, the Saint-Germain was required to provide the city terminus for two other railways. Under the guidance of the French state, a network was growing. The Chemin de fer de l'Ouest branched off at Asnières in 1839 to run to Versailles, and then in 1843 the Chemin de fer de Paris à Rouen branched off a little farther west. The Rouen railway was trouble.

The immense difference in travel time made Le Pecq a good place to transfer to and from river boats running further down stream. But a transfer at Rouen cut out even more of the slow boat journey. The Saint-Germain found its revenue drop from 812,000 francs in 1840 and 450,000 in 1844. Some of it was offset by tolls paid by the two tenant railways, but much of that was eaten up by enlarging the Paris "pier" at Saint-Lazare to eight tracks. That four were for Saint-Germain and two each for Versailles and Rouen indicates the relative usage.

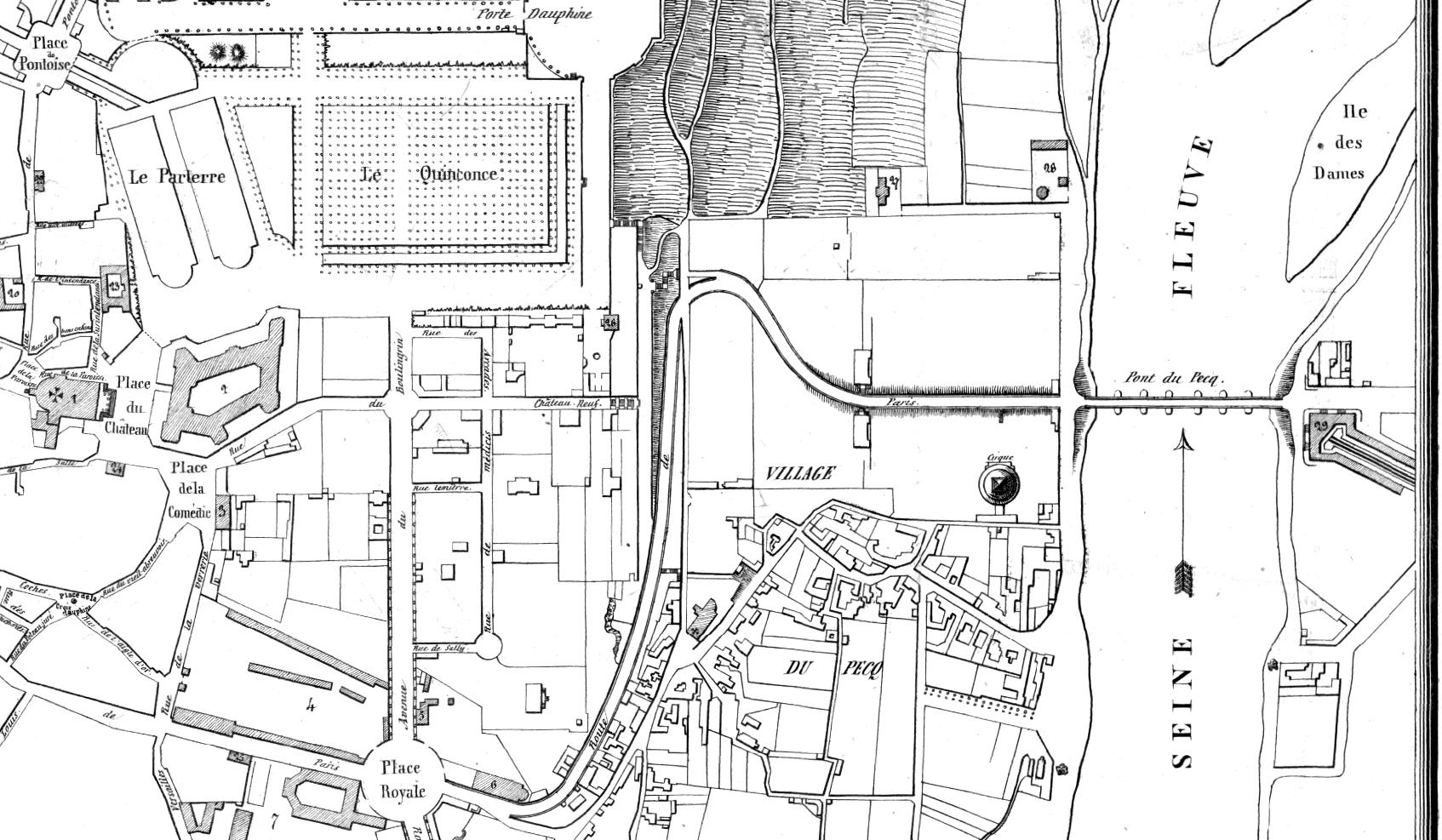

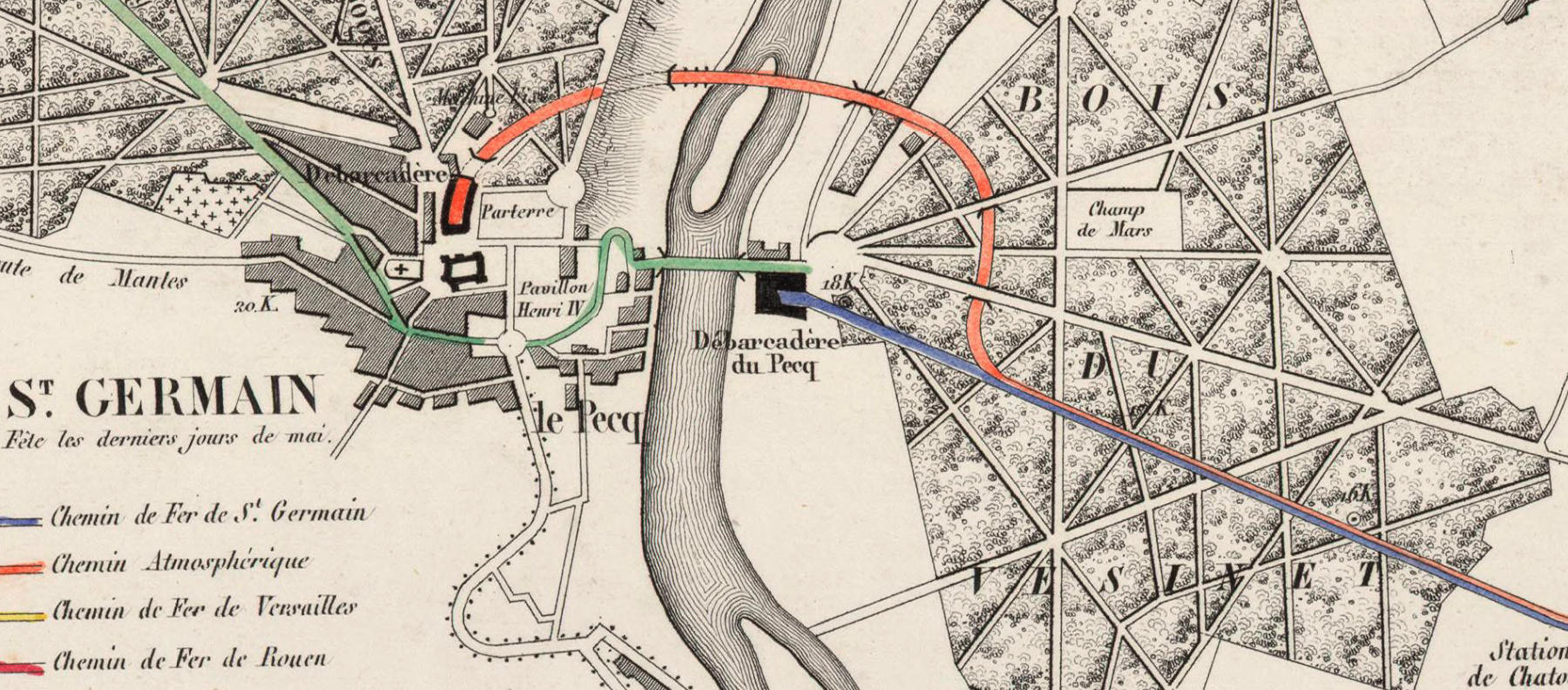

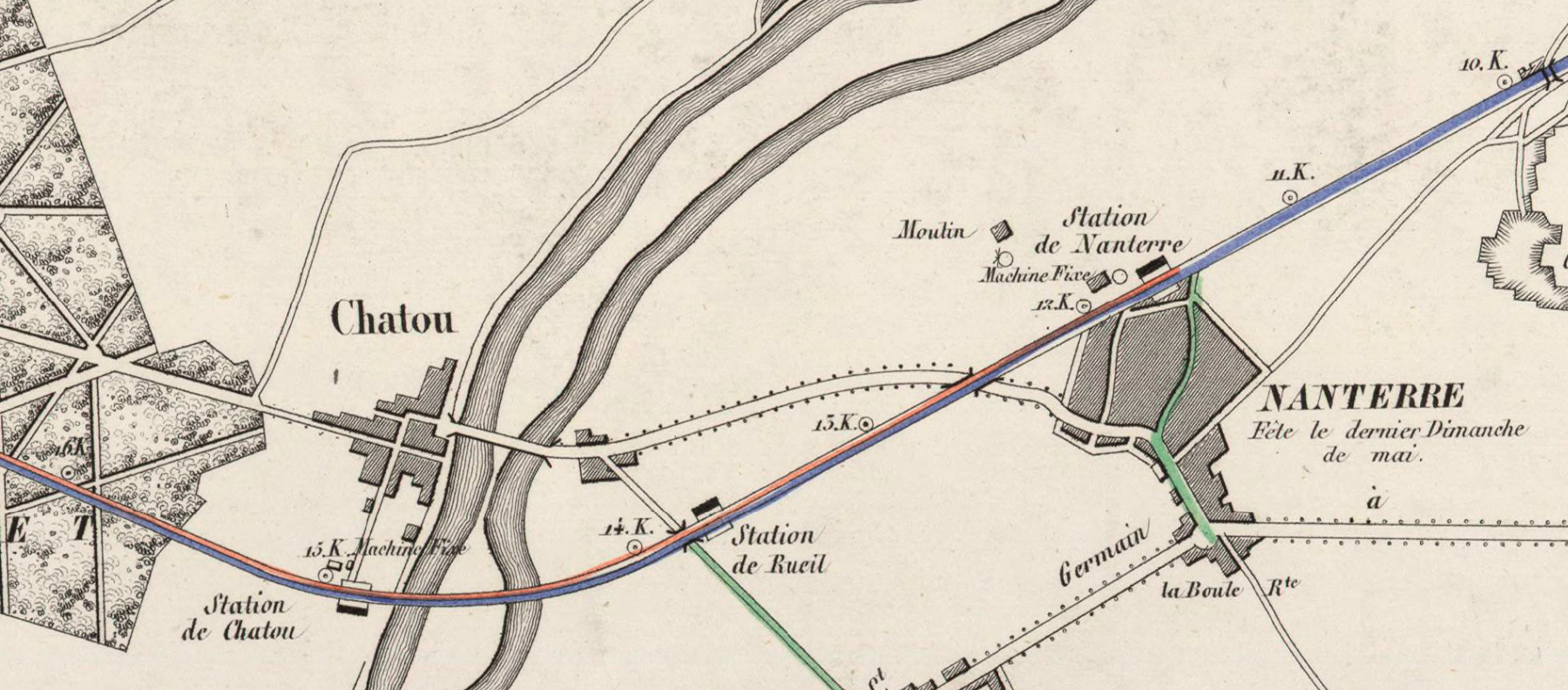

The map below shows the Saint-Germain railway and the two related railways in 1843, and the location of the atmospheric extension that was approved the next year.

Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda's book on atmospheric railways was published in French in 1842, and it touched off great interest. The French were very competitive with the English, and several engineers came forward to try to do it better. The Ponts and Chaussées (Bridges and Roadways) council sent one of their top engineers, Jacques Mallet, to view operations at Dalkey. He was on site from 12 to 14 November 1843, when the atmospheric was still in test runs, and he spoke with the Samuda brothers. In Mallet's favorable report in January 1844, he pointed out the lightweight rails that were used, contrasting them with the heavier rails on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway that had been replaced three times in twelve years because of the stresses of locomotives. Mallet noticed also that the awkward curves on the Dalkey line were no obstacle. In light of the report and shrinking revenues, the Saint-Germain company sent its own team of Isaac Periere and company engineer Eugène Flachat to Ireland in November.

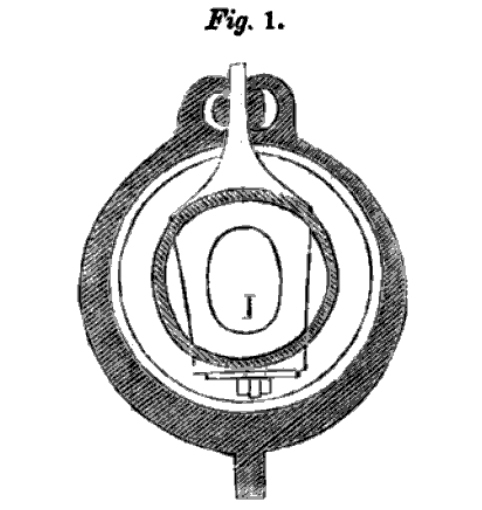

The French engineers correctly viewed the linear valve as the most likely cause of failure. Of their inventions the one that came closest to success was that of Alexis Hallette. The story is that while thinking about it he slid a pencil across his lips, inspiring him to design a linear valve with "lips" on each side. They were something like hoses, fitted into concavities in the iron, and inflated by atmospheric pressure until they touched each other. The arm from the piston carriage went straight down between the lips, eliminating the "handedness" that required extra work to change direction on Samuda lines. Mallet viewed Hallette's demonstration line at Arras from 23 to 26 December 1844 and returned praising it as better than the English design at maintaining vacuum. A lit candle held near the valve in vacuum did not flicker. He admitted that the valve had its problems, like a few times when the lips came loose and were sucked into the main pipe, causing a loss of vacuum. The hose was made of layers of fabric and rubber, and the arm from the piston carriage had a leather covering where it rubbed against the lips.

— The Patent Journal and Inventors' Magazine, 1846.

Even before the work of Hallette and others could be evaluated, back in March 1844 Mallet urged Ponts and Chaussées to make a decision, before too many more railways were designed and built with the supposed limits of locomotives in mind. If grades of up to 3 per cent were allowed it would reduce spending on cuts and fills. During July and August the council worked out a plan to spend 1,800,000 francs of the state's money toward a test railway, to be built with one part nearly level and another with a grade up to 3 per cent. Either the Samuda patents or those of Hallette could be used, but if the former, there had to be at least 2 kilometers of steep grade.

In his "Chemins de fer atmosphériques", Paul Smith points out that although the council suggested four locations for trials, the requirements they made fit very well to the needs of the Saint-Germain company. Émile Periere lived in Saint-Germain and by his influence, in September 1844 the municipal council appropriated 200,000 francs for the company to build from Nanterre to Saint-Germain, a route that conformed to the council's requirements by starting out flat from Nanterre to a point in the forest of Vésinet and then going up a grade of 3 per cent. But not in conformance, the contract provided that if the company found that the flat portion would be too expensive to operate, the municipality would be satisfied with atmospheric operation only on the portion that reached Saint-Germain. Of course they would. Getting trains up to the top was what they cared about.

Things moved quickly then. In November Periere got unanimous approval from the stockholders of the Saint-Germain railway, and they agreed with his idea of the terminus being as close as possible to the Château. Ponts and Chaussées approved, and, most importantly, consent was obtained from King Louis-Phillippe to build the new railway within his forests of Vésinet and Saint-Germain. By December trees were being felled in both places.

Below are details of a map of the entire railway from Paris to Saint-Germain, avec sa partie atmosphérique that was still under construction at the map date of 1846. They are particularly interesting because they document the locations of the nearly forgotten engine houses at Chatou and Nanterre, as Machine Fixe, and they prove that an intermediate station at Rueil was already there. At those three stations a black box is shown on the far side from the titular town, so I don't know what it indicates. The station building would be on the near side, wouldn't it?

— Perrot, Chemin de fer de St Germain avec sa partie atmosphérique... (details), 1846. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF.

The location of the junction in the forest of Vésinet is not correct. It should be at the 17.K mark (under "DU"), giving a much smoother curve, but let's keep in mind that the atmosphérique was not yet finished when the map was published. From the perspective of Paris (what else matters?) the Saint-Lazare terminus was sometimes called the Embarcadère and those at Le Pecq and Saint-Germain were therefore Débarcadère. Connecting bus routes are in green.

In March 1845 the company announced the decision to use the Samuda system. They planned to use 25-inch tubes on the grade and 15-inch on the flat section. To do this they proposed to use Samuda's variable diameter piston, which was never implemented anywhere.

The atmospheric was a new railway from an embranchement in the forest of Vésinet. In April 1845 Ponts and Chaussées reviewed and approved the exact routing. Two important roads in the forest crossed over the railway by bridge, and after that the railway would start up the grade, with bridges over the two channels of the Seine and a high viaduct approaching the hill, into which was a tunnel, followed by an open cut, and another tunnel up to the below-grade terminal.

Work began at once. It was well in hand at the end of 1845, except that no tubes had yet been delivered.

The French iron works were six months late from the date they were supposed to start delivering 1,800 ten foot sections of 15-inch tube and 850 of 25-inch. The company considered ordering pipes from England but tariffs made the cost prohibitive. Because of the delays the 25-inch pipes they needed to reach Saint-Germain were not fully installed until December 1846. In the meantime the three engine houses were erected and the engines were installed. Hallette's company was given the honor of supplying the enormous 400 horsepower Saint-Germain engines. The others of 200 horsepower were installed at Chatou and Nanterre but never used.

In September 1846 Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Joseph d'Aguilar Samuda were in Paris. Flachat had met Brunel twenty years earlier during the Thames Tunnel work. Samuda could say that the Dalkey railway was running well and that the London and Croydon had resumed atmospheric operation in July after replacing the valves. Brunel's South Devon Railway opened in May from Exeter to Teignmouth, but using locomotives because the atmospheric equipment was still being installed. Brunel and Samuda reviewed the work in progress and congratulated Flachat.

Test runs from January 1847 led finally to a public opening on 14 April. There were 16 trains scheduled each way, with a normal consist of seven passenger cars and a baggage car, running through with a change of power in the forest of Vésinet.

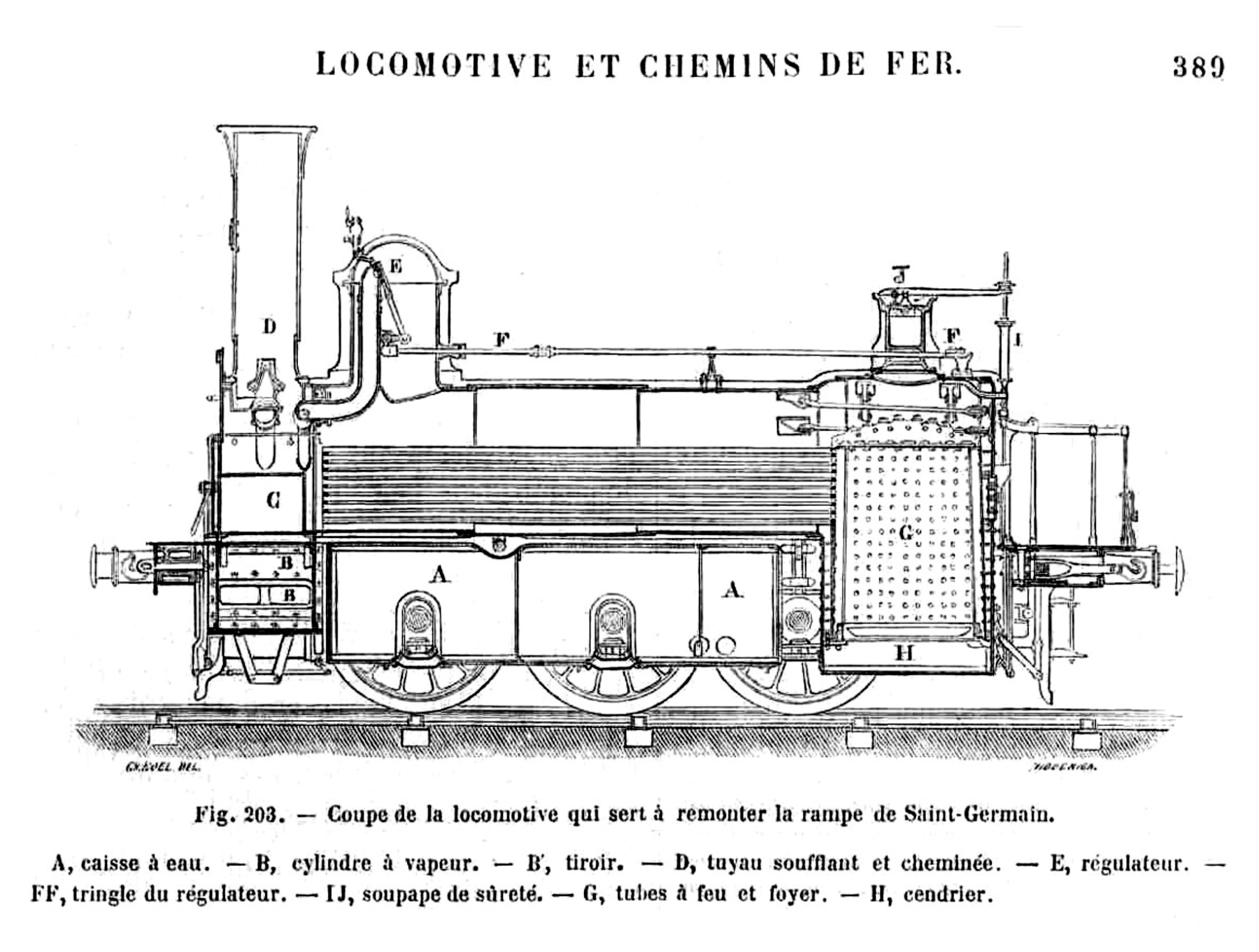

Amidst all this Eugène Flachat designed and built a small but powerful locomotive, Hercule, an 0-6-0 tank with 48-inch diameter wheels. From June 1846 it was used to bring construction materials to work sites on the railway. A test on 21 June showed that it could haul 48 tonnes up a grade exceeding 3 per cent without slipping. The company had a financial obligation to demonstrate atmospheric power, and yet now their engineer had demonstrated that they hardly needed it. Flachat had the entire new railway built for two tracks, so that Hercule could rescue stuck trains as needed, which happened several times in 1847. A second Flachat locomotive a year later, the larger 0-6-2 Antée, was able to pull 77 tonnes, a twelve car train. Admittedly the atmospheric could go up the grade twice as fast, but that was its only advantage.

Meanwhile, the Croydon discontinued atmospheric operation in May 1847.

— Hercule, from Louis Figuier, Les merveilles de la science, ou, description populaire des inventions modernes, 1867, via Paul Smith.

Before the end of 1847 the Saint-Germain company petitioned to get out of implementing the flat section. With experience Flachat argued that it would cost twice as much as locomotives to operate, and that the Samuda system of switching between tracks had been shown defective in England— an interesting comment on whatever the Croydon had done— and that passing between tubes could be done only at low speed— a remark based most likely on South Devon tests. Ponts and Chaussées concurred but required the engine houses at Chatou and Nanterre to be kept up until the end of 1850, in case atmospheric operation could be improved.

They did not last that long. Unrest with the French government had begun during 1847 as a response to economic problems caused by corruption and foolishness, with high tariffs on imports that caused business failures, and scarcities that deprived the poor of work and goods. In February 1848 crowds of desperate workers in Paris rioted, barricading the streets and setting fire to buildings. Specifically to our story, they attacked the railway, badly damaging the unused engine houses at Nanterre and Chatou and burning down the railway bridge at Asnières. They chanted, À bas les chemins de fer! On n'en veut plus!— "Down with railways! We don't want any more!" They threatened the jobs of the horse and wagon men. King Louis-Phillipe abdicated and left France, and the Assembly he had worked with now abolished the monarchy and declared the Second Republic.

The first president elected under the Second Republic was Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of the late Emperor of the French. Near the end of his term of office in 1852, he announced that he rejected the constitution and named himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. Somehow enough people went along with it that his self-declared empire continued for eighteen years. Under his reign the economy did improve and much work was done to rebuild Paris. The emperor made a priority of consolidating French railways into six large systems that would be backed by government guarantees. The effect on the Saint Germain line was that in 1855 it became part of a new Chemins de fer de l'Ouest (notice the plural chemins) that consolidated, among others, the old Ouest, Saint-Germain, and Rouen companies. It was under the new Ouest company that the atmospheric railway was converted to locomotive working in 1860. On the Saint-Germain page I will detail operations of the atmospheric railway and its survival as the last of its kind. Here I want to examine the remains of the atmospheric in the area of Le Vésinet and Le Pecq.

NANTERRE

The station site is within the limits of the much larger RER station Nanterre–Ville, the longer name distinguishing it from Nanterre–Université, the next station closer to Paris. The old station was along the north edge of the village and the engine house was on the north side near the eastern end of the RER station. Nothing remains.

CHATOU

The station site is within the limits of the much larger RER station Chatou–Crossy, near the west end. The station was a short distance south of the village proper. The engine house was on the north side, toward the west end of the RER station, west of the quaint street seen from the train. Nothing remains.

LE PECQ Débarcadère

When I began researching the Saint-Germain railway I assumed that the riverside Le Pecq station was closed in favor of a new station on the atmospheric alignment, but that does not seem to be true. For one thing the company may have wanted to continue whatever river transfer business it could get.

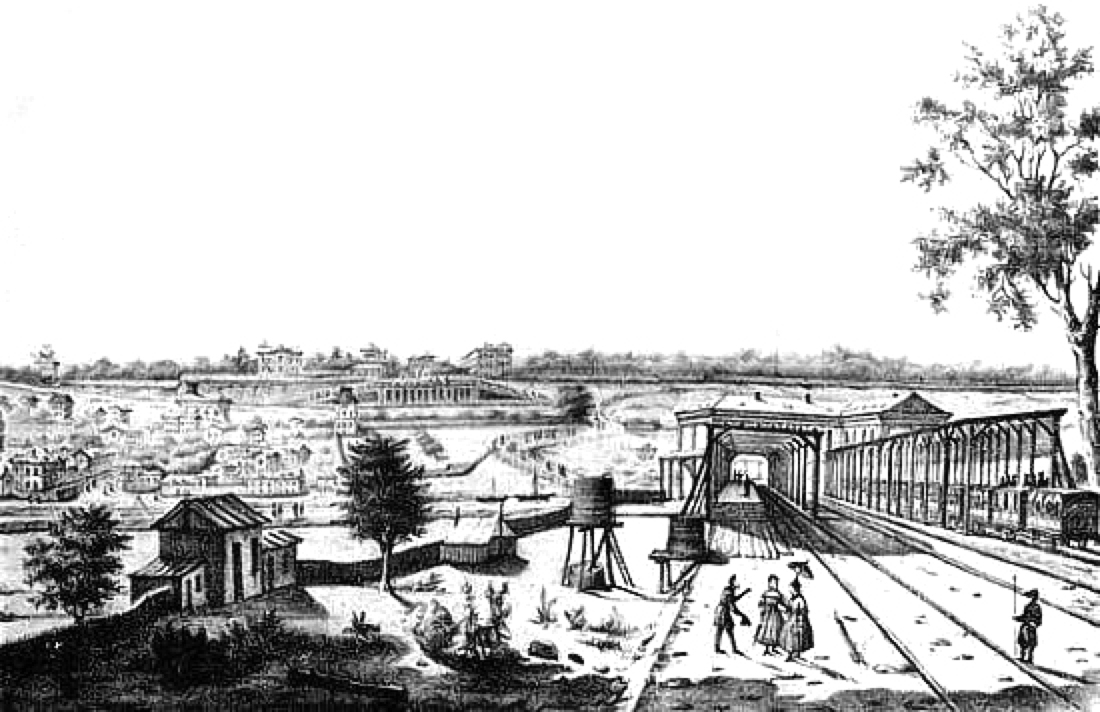

The illustration below shows the riverside terminal with three tracks and two platforms. The center track woud be an escape track for the locomotive to run around the train. It's possible that the left side was for arriving trains, and the right side, next to the station house, was for departures. Many early railways followed this practice despite the shunting of empty rolling stock that it requires. French railways run left-handed based on English practice.

In the distance is the plateau of Saint-Germain. The wall with mostly blind arches (two have openings) and sloping wings is a remnant of the Château Neuf project that is still there today, though the view of it from a distance is now largely obscured by trees. The large Château Vieux is immediately to the right of the arches, and to the right of that is the long horizontal plane of the Terrasse.

— Le Pecq terminus, source unknown. A copy is on an information board nearby in front of the Bibliotheque Eugéne Flachat, Le Pecq.

Galignani's New Paris Guide, 1861, tells us, "Since the suppression of the atmospheric railway, which has been found too costly, and liable to frequent repairs, the old station of Pecq, a village on the banks of the Seine below St. Germain, has been restored." It sounds as if the atmospheric section was closed for as long as a year. In addition to removing the pipe, the company probably replaced the trackbed and laid heavier rail, and the terminus at Saint-Germain must have undergone significant changes to handle locomotives and supply them with coal and water.

Below is a military map from 1865, with features considered important in red. Unfortunately the name of the circular Place royale is clumsily placed directly over the Pont du Pecq, obscuring the old Le Pecq terminus as well, but clearly it was still on the map and even got red coloring. The Saint-Germain Débarcadère is also surrounded by red. Notice that "le Pecq" spans both sides. In the forest of Vésinet we see a Champ de manœuvre. Five years later Napoleon III brought France into a disastrous war with the newly formed German Empire.

— Detail, Dépôt de la Guerre, Carte d' État-major de la France, Feuille Paris S.O., 1865.

The old terminus was not in use much longer than the 1860s. But it was not completely demolished until 2017. Whatever was built on the site during the previous century and a half must have had shallow foundations, because those of the railway terminus remained in the ground. Late in 2016, after removing old buildings on the site, a developer had excavated only ten feet or so before coming across turntables and stone walls.

The Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (Inrap) was called in and had possession of the site from March to May 2017. The rails had been lifted, but most of the foundation of northern part of the building was still there. The terminus extended a little closer to the river, beyond the work site, but still what was found included a waiting room, a hotel, a restaurant, and toilets, and also storage rooms and coal bins. Pieces of ceramic dishes and buttons from staff uniforms were found.

— Imagery © 2017 Google.

Google's Satellite view happened to catch the site within the three months it was open. The alignment of the three tracks is visible and what appear to be turntables on all three. The station building was partly to the left in land yet unexcavated. The foundations along the north side were those of the greatest interest. See the Inrap site for photographs of the dig. They call it la première gare de voyaguers de France, recognizing that the Paris terminus in 1837 was a temporary expedient while the Le Pecq terminus was intended to be a lasting monument to the company.

LE VÉSINET–CENTRE

Le Vésinet is a planned garden city, among the first in the world. The forest land, previously royal property, was acquired from the emperor in 1857. Pallu and Company laid out roads, parks, and lakes and streams, and began selling lots in 1858. An Act of 1875 confirmed the many regulations issued up to that date restricting almost everything that could be built. The town is to this day a very desirable and expensive residential community. The book Notre métro by Jean Robert says that a Vésinet station opened in 1859, but I can't tell which site (this or Le Pecq), and anyway based on the Galignani guide book it would have closed when trains were diverted temporarily to Le Pecq riverside. More likely I think, the first station at at this site opened in 1861 when locomotives began running on the former atmospheric railway. It was replaced in 1972 by the RER station.

LE VÉSINET–LE PECQ

A remarkable thing about this location is that on maps from the atmospheric age, no station is shown here, where motive power was changed. Trains had to stop, but it was an isolated spot in the woods with buildings for railway crews. It may have been a halt for hikers, and it may have been the site mentioned in the Notre métro book.

The other remarkable thing is that there was no engine house. Running east, trains ran down the grade from Saint-Germain by gravity, and the engine house at Chatou could have pulled them on the flat section from here if it had ever come into use. But running west? Evidently the giant engines at Saint-Germain were expected to pull all the way from Chatou, about four miles in total, some of it on a steep grade.

What surprised me too, on my first time here, was that the railway does not begin to rise near the embranchement from the original route. Instead it runs at ground level with roads crossing over, until it is past the Route de Montesson. Only then, finally, it begins to ascend. It was of course part of the atmospheric promotion that less money need be spent on cuts and fills since steeper grades were possible.

The first proper station at this site, called Le Pecq, opened in 1861 when locomotives began running. It was conveniently located just east of the Route de Montesson bridge. After a long life the station was replaced in 1955 by an establishment west of the road bridge, but the 1861 house was retained for railway purposes. The RER station of 1972 is east of both, at the location of the atmospheric transfer stop, and it was given the proper name that the town had wanted for decades, Le Vésinet–Le Pecq— because it is not in Le Pecq!

Both the 1861 and 1955 station buildings continued to be used by the railway but the former was soon abandoned. The town of Le Vésinet acquired it in 2018, believing it to be an historic station of the atmospheric railway. The structure was in bad condition by then, and despite repairs that made it possible to rent it out to a bicycle repair shop, a beam collapsed in August 2019, dropping part of a wall on the tracks. There are plans to restore the building.

The postcard below shows a train at the 1861 station, seen in approximately 1900. The atmospheric station was most likely in the open space beyond the station, and the wooden freight house in the background might be a holdover from that time. During the RER reconstruction, if not earlier, it was removed.

— Postcard view. "Le Vésinet — La Gare du Pecq."

My photo below is from as close as I could get to the same angle. The yellow structure that keeps fools from touching the wires also blocks photography.

My photograph of October 2019 shows the damage from the collapse two months earlier. On the street side the walls were shored up with heavy timbers. Beyond the bridge you can see some of the 1955 station.

THE BRIDGES AND VIADUCT AT LE PECQ

The crossing of the Seine at Le Pecq is the most monumental structure built for any of the atmospheric railways. It comprises two bridges across the river, separated by an earth embankment on the Île Corbière, followed by a stone viaduct of twenty arches leading to a tunnel into the cliff at Saint-Germain. The railway goes up a grade of about 2½ per cent beginning near the first bridge and increasing to 3½ per cent as it nears the end of the stone viaduct.

Each of the original bridges had wooden arches pushing against masonry piers in the river, against abutments on the east side and on the island, and against the first arch of the viaduct on the west side. The design of the bridges was said to be the same as the company's bridge at Asnières, which was burned down in 1848. Its replacement of the same design suffered the same fate in the Prussian siege of Paris in 1871. The bridges at Le Pecq were ignored during both events. Too far from Paris?

Below is a detail of a painting showing the Asnières bridge after it was burned down the second time. It shows clearly how the wooden arches rested on the masonry supports. They are nearly identical to those at Le Pecq.

— Adolf von Becker, "The Bridge at Asnières after the Siege of Paris in 1871" (detail), Finnish National Gallery.

The bridges at Le Pecq stood until 1885, when they were replaced with steel lattice girder deck truss spans in order to safely accommodate heavy locomotives. The same masonry supports were used. The last span on the rive gauche was dropped by an Allied bomb on 5 June 1944. Were the bridges replaced during the renovations for the RER? The stations were totally rebuilt, and tracks rearranged, and overhead electrification was installed. If the railway was closed for a while, it would have been the perfect opportunity to replace steel bridge spans that were in their ninth decade. But they look the same in the old photographs we're about to see.

Certainly the arched viaduct is barely changed at all. The addition of poles and cross bars for the overhead electric power and a walkway on each side does little to reduce the impact of Flachat's achievement.

Let's go.

On foot the crossing is a bit over a mile from the stations at Le Vésinet–Le Pecq or Saint-Germain, but from the former it's level, so that was my choice. Walk along the Route de Montesson, and at the circular Place de la République, you enter Le Pecq, marked by the presence of commercial buildings in the border area. Walk over the north side of the Pont Georges-Pompidou (1963). Look down stream.

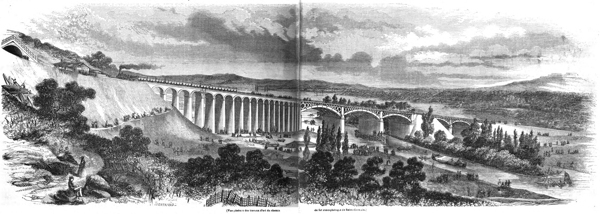

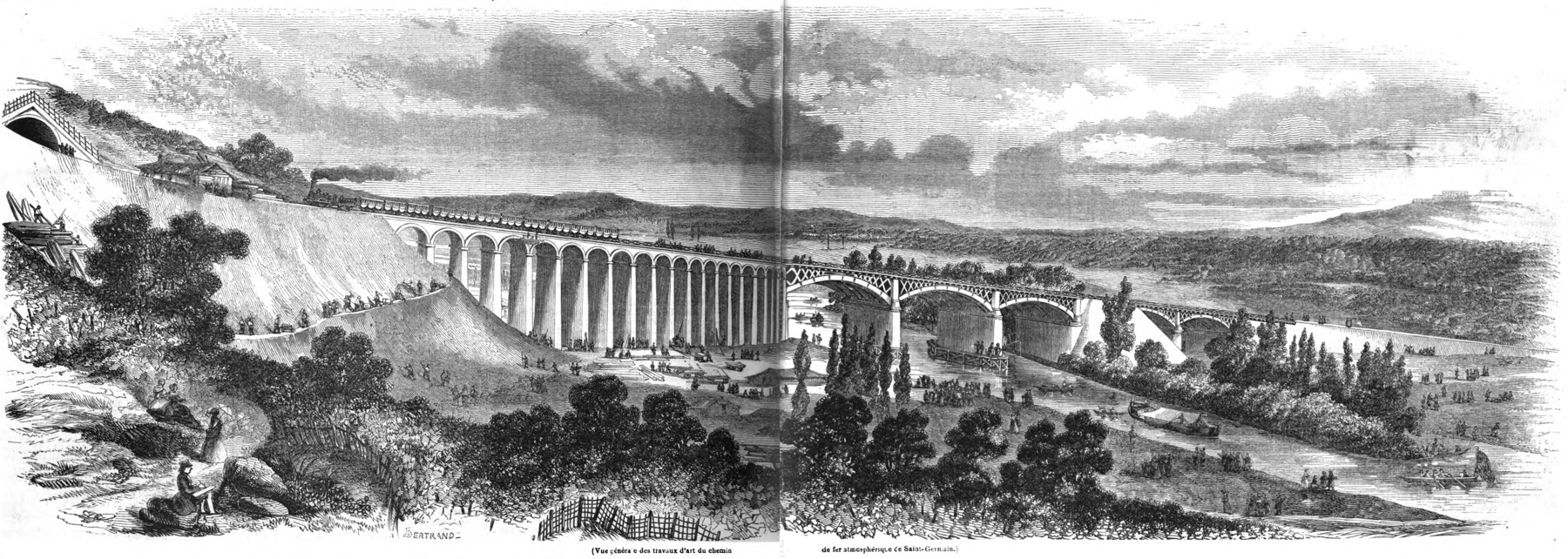

Below is a panorama of the "works of art" drawn about five months before the railway opened, with workmen busy all over, and the usual tourists sketching and gesturing. The similarity of the bridge to that at Asnières is clear. Missing the point, the artist Bertrand drew a locomotive pulling a passenger train up the exaggerated incline.

— Bertrand, "Vue général e des travaux d'art du chemin de fer atmosphéric de Saint-Germain", L'Illustration, 29 August 1846.

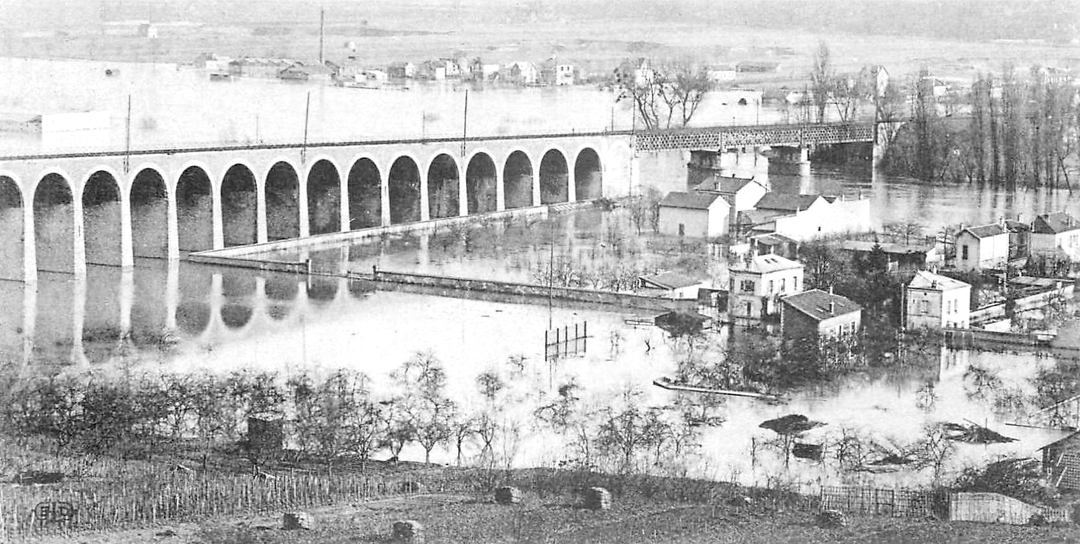

Below is a view from 1910 that shows the viaduct and some of the 1885 bridge spans. The subject was the Great Flood of Paris, which crested on 28 January 1910 at 28 feet above normal in the city. Under those conditions the bridge piers look much shorter.

— Postcard. "Crue de la Seine / Le Pecq — Le Viaduc / Le 1er Février 1910."

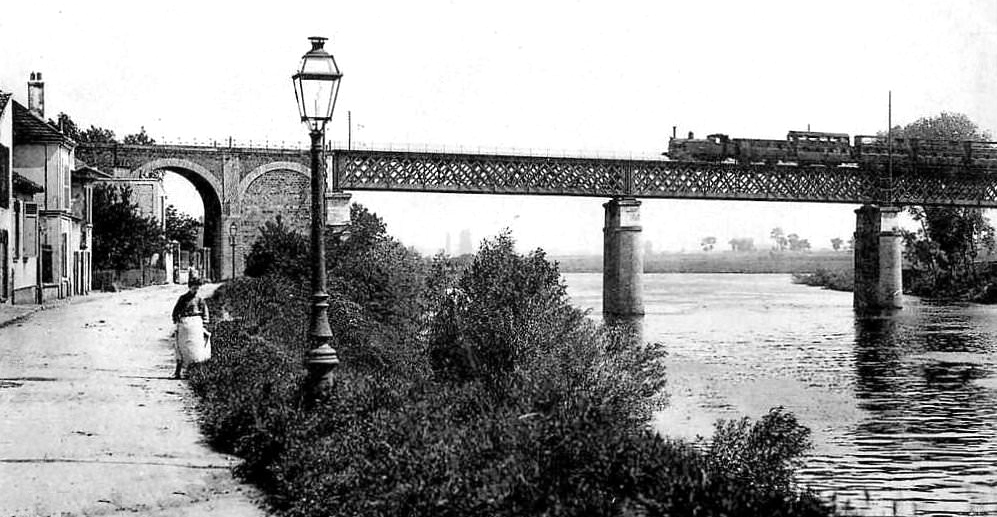

Another postcard shows the path leading to the viaduct. The first arch is filled in because it supported the last arch of the old bridge span.

— Postcard. "Le Pecq — Le Pont du Chemin de fer et la Cité."

October 2018. I approached the viaduct on the street called Quai Voltaire. On the right, between the road and the river, is Le Parc Corbière, which becomes much wider north of the viaduct. The road in the postcard and the row of houses are no longer there.

Below, two views looking west. A close look at the first one shows the viaduct beginning to curve left as it approaches the hill.

Below, four views looking east, showing the bridge and the filled-in arch. The closest bridge span is the one that was replaced after the Allied bomb knocked it down.

Below, three views looking south and west.

October 2019. Below, the view south from the RER train. In the distance on the plateau of Saint-Germain, near the left is the gigantic Château, with the arched wall below and to its left. A little farther right is the straight horizon line formed by the clipped trees back of the Terrasse. We'll see those again.

Saint-Germain, next stop.