South Devon Railway

Dawlish

In which Joe visits the popular rail photo site, and tries to find where the engine house was.

Explorations: 26 June and 11 October 2018, and 20 October 2019.

Journey: Paddington to Exeter St Davids, and St Davids to Dawlish.

-

OFTEN CITED REFERENCES

- Paul Garnsworthy, editor, Brunel's Atmospheric Railway, The Broad Gauge Society, 2013.

- Peter Kay, Exeter–Newton Abbot: a Railway History, Platform 5, 1991, and excerpts in Garnsworthy.

- Howard Clayton, The Atmospheric Railways, the author, 1966.

- Charles Hadfield, Atmospheric Railways, David and Charles, 1967.

- G.A. Sekon, A History of the Great Western Railway, Digby, Long, 1895.

The fifth engine house was at Dawlish. Construction began around January 1846, six months after Exeter St Davids. Starcross and Dawlish stations were sited in similar situations near a sea wall, and the station houses were built to the same design. Once again the platform was along a loop track about 300 feet long, and a trainshed protected only that track and the platform. In the case of Dawlish the wooden station house burned down in 1873, so unlike the one at Starcross it had to be replaced within just a few decades. The building in use today was opened in 1875.

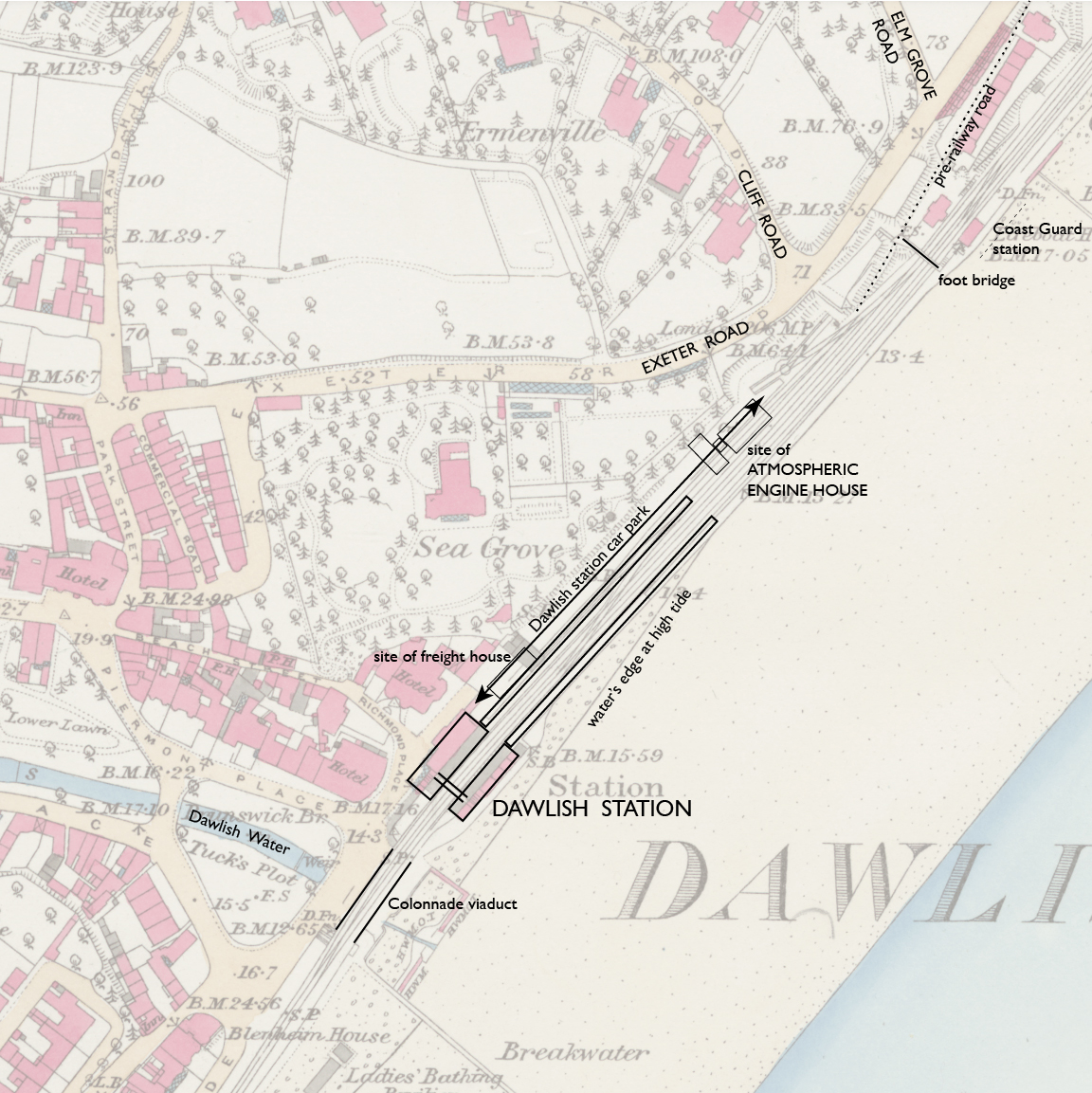

The engine house was north of the station, where the railway is on a narrow shelf of land between the sea and a red sandstone cliff. The buildings had a back wall near or directly against the cliff face. They were demolished in 1873 to make room for freight sidings. We'll consider the exact location shortly.

Dawlish itself is a very ancient village. The oldest documentation is a charter from King Eadward in 1044 that refers to it as already inhabited. It was not quite a coastal town. The center of old Dawlish was more than half a mile inland, around what are now called Old Town Street and Church Street, along the small river called Dawlish Water— a redundant name if the "ish" is the word for water as in the river names Exe and Esk. Like other places on the Devon coast, it began to attract seasonal resort visitors by 1800. Coming from Exeter, Dawlish is the first place reached that is on the English Channel rather than the Exe estuary, and therefore the first that can offer sea bathing. To supplement the beach, the Dawlish Water was made the centerpiece of a new part of town, with little waterfalls, well gardened banks, and rows of guest houses on each side.

— Dawlish station and engine house, Ordnance Survey 25-inch, 1890. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 courtesy National Library of Scotland.

Annotations by Joseph Brennan.

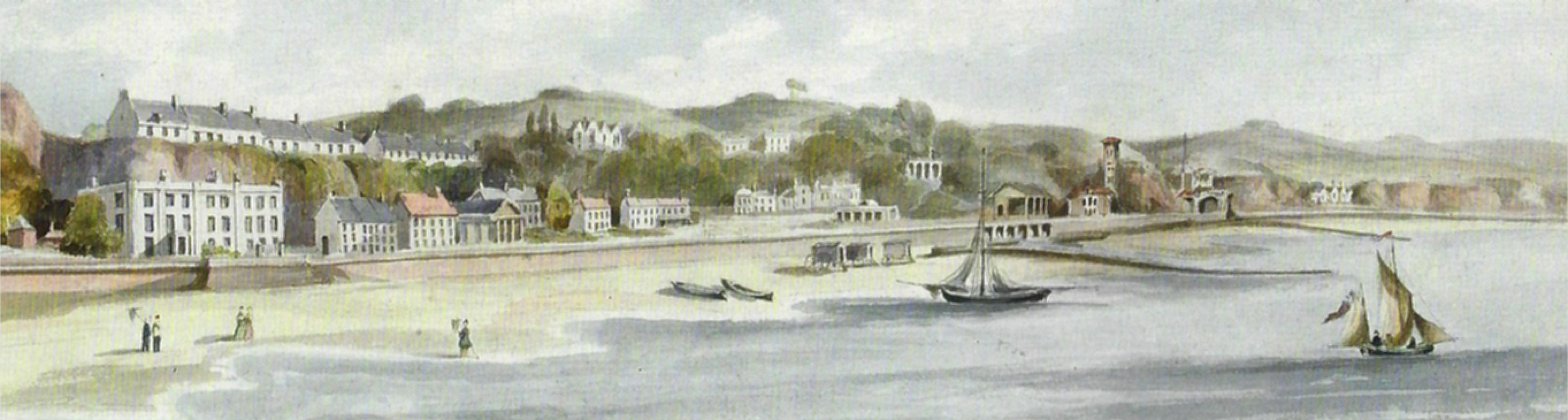

We have once again a William Dawson painting, but at this location he was not so concerned with the railway facilities, there being plenty of interest in the town itself. Beyond the tall-masted boat we see the colonnade where the Dawlish Water passes under the railway, and the railway station with its trainshed open on the water side. Beyond that we see the chimney of the engine house and a building this side of it, both with red roofs. The bridge over the railway past that is the access to the Coast Guard station, where there is still a foot bridge today.

— William Dawson, "From the Kennaway Tunnel Dawlish to Langstone Sands. View North of the Line." via Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

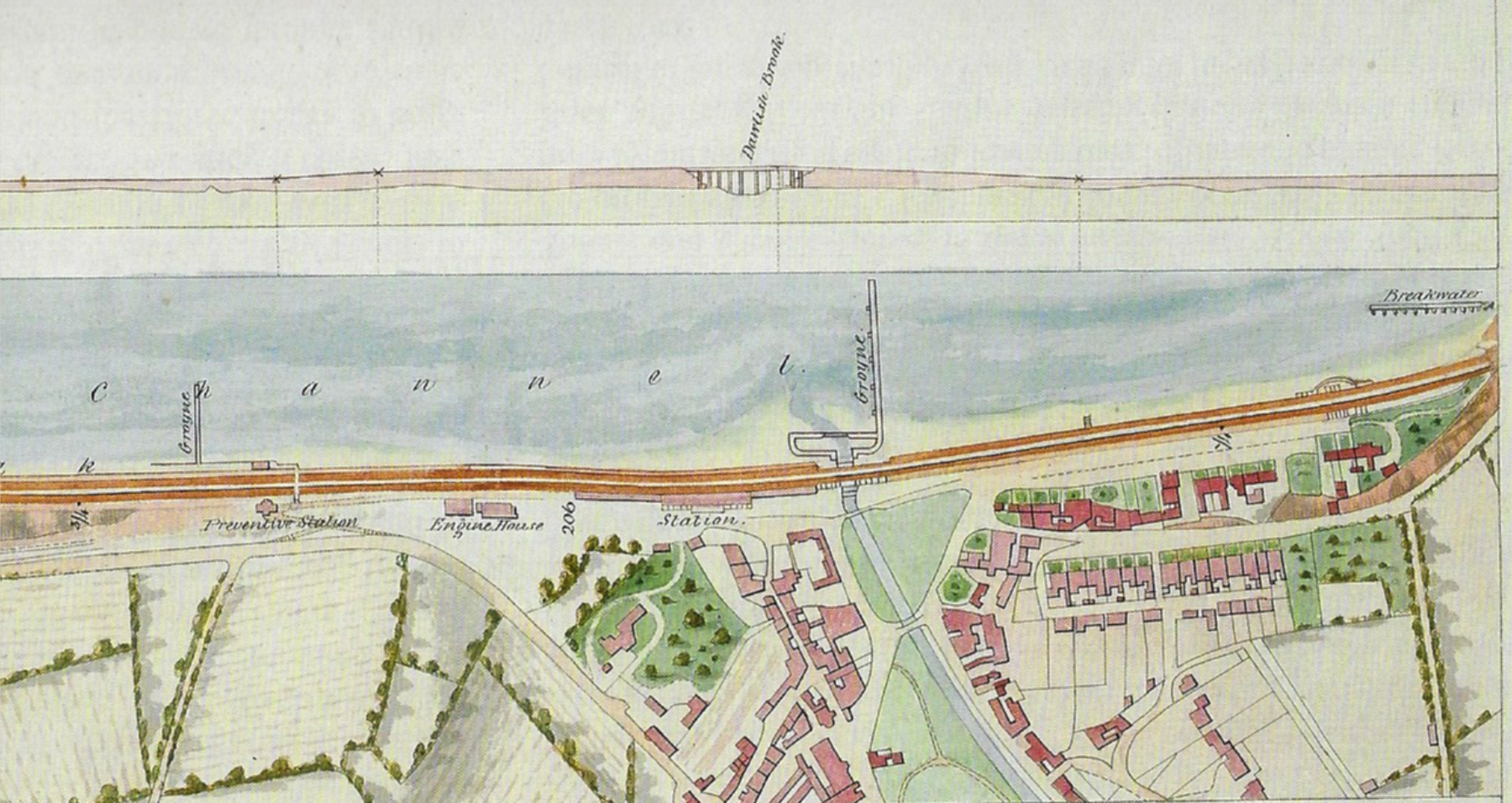

Dawson provided a plan and profile for each location of his paintings. The book Brunel's Atmospheric Railway includes all of them, but I have not shown a plan since Exeter St Davids, or any of the profiles since they were so flat up to this point. The vertical exaggeration in the profile reveals the slight grades around the colonnade for the "Dawlish Brook" as he calls it. Below, we can see a little more clearly where the engine house was.

— William Dawson, plan and profile at Dawlish, via Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.

Actually it's not that clear where the engine house was. The road he shows in line with the "Preventive Station" does not correspond to the modern Elm Grove Road, but I think it's supposed to be the same.

Our point of interest is that the "Engine House" is shown as two rectangles with their long axes parallel to the railway, with a small rectangle between them that would be the chimney. This arrangement makes sense, since the buildings had to fit between the railway and the cliff. But in his own painting, the building this side of the chimney seems to have its white side wall with three windows running out from the cliff, not parallel to it. And here begins the inconsistencies.

As he did at Starcross, Nicholas Condy again gives us a good view of the atmospheric railway. The boiler house is nearest, then the chimney, and finally, somewhat obscured, the taller engine house proper. The roof makes it appear to be at a right angle to the railway and cliff. It certainly has only one window above and below on the side facing the sea.

— Nicholas Condy, "Dawlish" (title at bottom center). Ironbridge Gorge Museum.

In front of the boiler house, we see wagons and a pile of coal, although no sign of railway track. Rough cliff face intrudes on the right. Behind the boiler house is a dressed stone wall against the cliff. It is hard to tell whether there is a space between the wall and the building. The chimney may be aligned with the back wall of the boiler house, and there is a small structure with two windows in front of it. The three windows shown by Dawson on the engine house will be on the far side from our view. That's what I see here.

The railway line itself has the same three pipes we saw in Condy's painting of Starcross. The small one, for the starting rope, has the same cap with a button. Here the pipe on the left looks smaller than the main 15-inch atmospheric pipe, but it is probably the same size as the one on the sea side at Dawlish, and it has the same mysterious inverted U attached. It's too bad we do not get a look at the points where the station loop track branches off, although Condy gives a sense of the main track curving to run past outside the trainshed.

The policeman with his two-disk signal is quite prominent. The poles on the other side of the track are for the telegraph. Peter Kay's book has a modern drawing of one with its little peaked roof. Condy does not bother to hint at the four wires, which were parallel vertically (later systems had poles with crossbars, and wires parallel horizontally). The Great Western style of broad gauge track is well shown. The bridge rail is laid on wooden beams, and the cross "baulks" were placed on the SDR at the correct intervals to support the ribs of the atmospheric pipe.

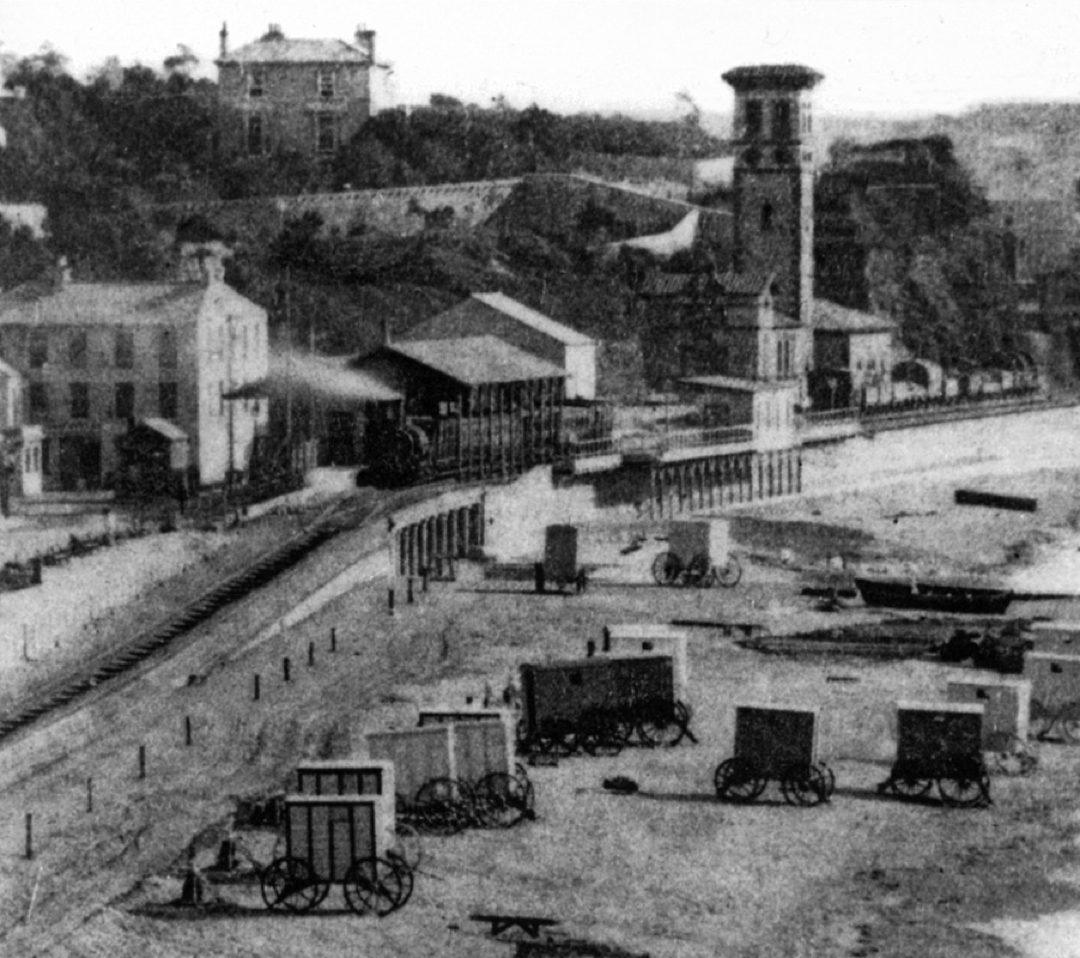

The next picture I have looks like an enlargement from an albumen print of a photograph. It is quite a bit foreshortened. The atmospheric is gone, but not too much else has changed. This is still broad gauge track. The 1846 station house on the land side is still there, with the trainshed open on the other side. A locomotive-drawn train is ready to go. The other track now has the platform and small house that were added in 1858. On the near side of the station is the colonnade that allows people and the Dawlish Water to cross under, and on the far side is the taller freight house, served by sidings we cannot see.

Of greatest interest to us is that we can see the complete set of atmospheric buildings, still intact at this tme. This is the only image I can find that shows clearly that the long side of the engine house runs 90 degrees from the railway, and goes farther back to the cliff than the other buildings. That this is a photograph makes it definitive. It matches very well with Condy's painting, but not at all well with the plan of Dawson the surveyor, who was on holiday from the precise measurements he normally had to do.

Given what we see there, we might expect remains of cliff-side walls to run deeper into the cliff where the engine house was, and less so to the north where the chimney and boiler house stood. But what we find today is a more consistent wall that gives the impression that all the buildings were set back to the same degree.

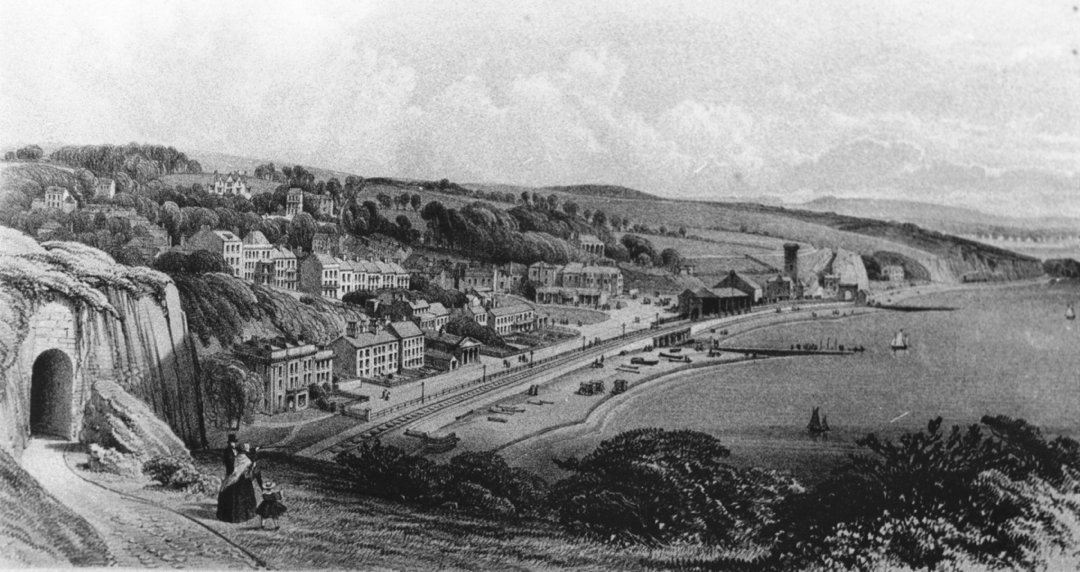

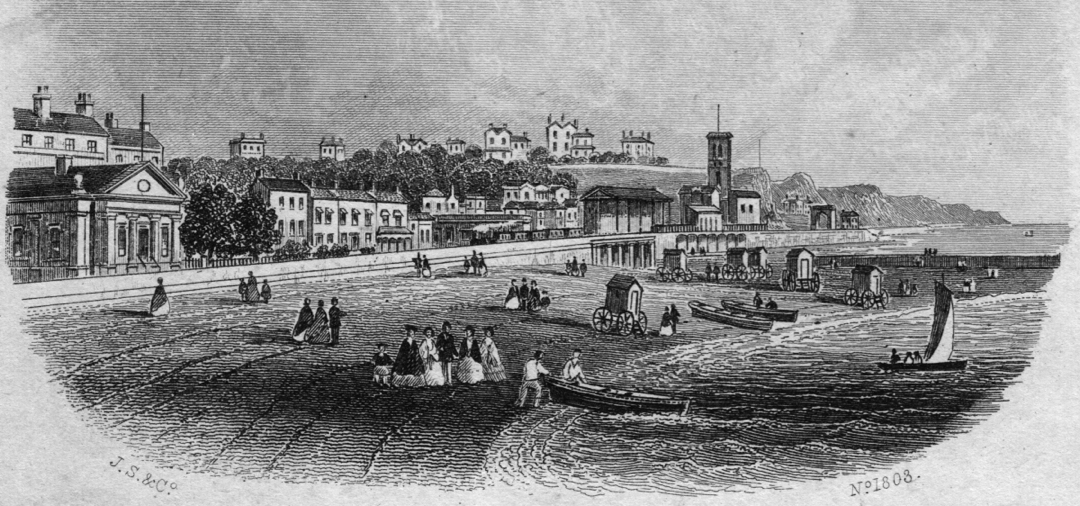

The Dawlish Local History Group has an article called "Dawlish Beaches 1770-2020" that includes the two drawings below. The first one does not show the platform and station house on the down side. It does show the freight house that Peter Kay dates to 1849, so it is post-atmospheric. The perspective is good, suggesting use of a camera obscura. The second one, a less precise rendering, has the down side station house of 1858, but not the freight house. The puzzling point of view is high above the edge of the water. Despite the distant view of the buildings we care about, both seem to show the engine house in the same orientation as the photograph.

Now back to our topic. Where am I going with this? I am trying to identify any part of the walls along the cliff today as remains of the atmospheric buildings. To start, let's check the photograph below, of uncertain origin but dated 1951. Peter Kay's book has a similar view dated 1922. The point of view is the footbridge to the Coast Guard station. I did not get to that location. In the photograph the freight sidings and the freight house are still in place and in use. They were removed in 1965, and not too long afterwards the property became the station parking lot, where we can walk today. Only the farthest reach, the foreground in the picture, is fenced off.

What interests us here is the wall against the cliff. It looks quite clean and new but that may be misleading since it appears to be the same as in the 1922 photograph (though that is not as clear). I think you can make out that there is a paved walkway along the top, that has a projecting viewpoint near the middle. Over to the right, there is a wall with its top sloping down to the left, which seems to be the same (or in the same place) as the wall in the old photograph, seen to the left and behind the chimney. If it is the same, then we know it comes down near the north end of the atmospheric buildings.

I find it very tempting to say that the viewpoint marks the spot of the chimney, and that the cliff was never cut back as much at that location, so that the back wall of the chimney could lean against it, avoiding the problem at Starcross. If so, then the boiler house would be along the nearer part of the wall, and the engine house would be along the farther part. Whether the evidence supports this is not clear.

My first view below shows the entire wall in question.

The wall begins at the left side of the picture. From there to the viewpoint it is vertical, with two sloping buttresses, the first visible and the second identical one obscured by foliage. At the top of the cliff is a setback of a few feet and then a few feet more vertically to protect the walkway.

That this section is longer than the section north of the viewpoint presents a problem, since the engine house frontage along the sea side was definitely shorter than that of the boiler house. But compare the wall visible above with the next picture, below.

The mess of crumbling bricks and mortar, and stones of varying sizes, is not to be seen in this part of the wall closer to the viewpoint. I will speculate that we have two different phases of construction here— aside from the modern brick at the very top. If so then maybe we can imagine that this part is the back wall of the engine house and the other represents some later cutting of the cliff to make room for the freight sidings. I have to point out that there is a little more of the bad brick near the bottom corner of the viewpoint.

A full-frontal view reveals the differences north and south of the viewpoint. The south side corner has some of the familiar red stone used at Starcross, but this is the only place we see it, not even on the other corner. The buttresses on the wall to the south are of concrete, those at the viewpoint of rough-cut stone, and those to the north, which are shorter, are a bit less rough and seem to be of different stone.

The WARNING signs on the buttresses are not about the wall, but the parking spaces. For the record, you are not allowed to park here overnight and sleep in your car.

I wonder about the horizontal band of brick under the viewpoint, which continues at the same height, but with narrow stone, on the northern wall, touching the tops of the two buttresses, and for that matter the horizontal crack a short distance above it. The crack may be for drainage. In the 1951 photograph you can see that the upper section of this wall is not vertical but slopes back.

The type of masonry work in the vertical lower wall, what we can see of it, looks similar to that of the nearby part of the south wall. They may be from the same construction period, but we don't know what period that is.

At some angles including this one, over there on the left is what appears to be a wide stone arch, filled in. I think it's an accident from laying stones of different shapes, but if you want to believe there was a chamber in the hillside... who am I to stop you?

— Image capture: Mar 2011, © Google

After I was home I noticed in Google Streetview that the cliff immediately south of the wall is interesting too. First of all there is a short section of red stone masonry that looks like the buildings at Starcross. Then south of it is exposed cliff, also of red stone, with indentations in it, as if large beasts had tried to make burrows.

Conclusion

I am not sure that any of the wall dates from the atmospheric period. The differences in construction certainly rule out that all of it does. The glimmer of hope is from the walls on each side of the viewpoint, which seem to match in style (with later buttresses). But those walls are such a crude contrast to what we see at the surviving engine houses (Starcross, Torquay, Totnes) that I am skeptical. One might argue that since the wall against the cliff would be visible only to railway staff inside the buildings, a lower standard of masonry might apply. What were Brunel's feelings on a matter like this? I don't know, but I think he wouldn't accept it.

One more thing: where was the water tank? Peter Kay's research found no mention of it. The similarities with Starcross station and engine house make me wonder what's under the parking lot, but it was unpaved for a long time when the freight sidings were there, so there was ample opportunity for someone to notice a round opening. Another possibility, for an open reservoir, might be the ground between the top of the cliff and the Exeter Road that seems to have been never built upon.

Visiting Dawlish

The first time we came to Dawlish it was a sunny day in June. I took the photos below looking south to the first of the five tunnels along the coast between here and Teignmouth. Since the footbridge stairs can be an obstacle, there is a level crossing protected by station staff, just this side of the colonnade bridge.

My second opportunity at Dawlish was on a rainy day in October. Bad time to go, right? Not at all. The waves slapped the windows of the Pacer as we approached. Exciting! It could have been worse. In January 2020 waves broke windows on a train near Dawlish, disrupting service for hours. That's more excitement than I need.

I walked around on the platforms snapping pictures, with the wind and rain hitting me pretty good. People walked under the colonnade to the beach and watched the fury of nature. I was sorry when it started to die down.

The same day, later, I took pictures at Starcross and Torquay, and neither you nor I would believe it was the same day except that I have the date from the camera.

On the rainy day, I grabbed a close-up of one of the famous black swans of Dawlish, and not only that, this was the only day that I thought to take a long shot of the Dawlish Water, so I give you that too.

Back on the sunny day, here are some of swans on a nest. I don't know who she is over there, but she looks all right, and I think she won't mind this picture.

Also on the sunny day, I could not resist the offer (see the sign on the right) of a cone of Old Fashioned Devonshire Ice Cream with... wait for it... Devon Clotted Cream on top. I realize that clotted cream is a disgusting name, and a dairy product unknown in America. I'm telling you, one taste and you're done for. It's perfect on a good scone, a thing we think we have in America, but we don't, really. Until I came here I had not thought of putting it on its cousin, ice cream, but this... well.

"Probably... The BEST Ice Cream in Town!" I sensed that some local controversy had been settled by qualifying the boast. But what was the story? After we finished off our cones I went back in and asked the two teen girls working the counter, why does the sign say "probably". They told me they didn't know. So neither do I. That's all.