Clifton Rocks Railway, Bristol

TODAY'S ITINERARY

Exploration: Saturday, 12 October, 2019

lv London Paddington 0800 Great Western Railway

ar Bristol Temple Meads 0941

lv Bristol Temple Meads, First Bristol (bus)

ar Clifton Village stop

lv Clifton Village stop, First Bristol (bus)

ar College Green stop

lv M Shed, Bristol Harbour Railway

ar Great Britain

lv Great Britain 1525 Bristol Ferry Boats

ar Bristol Temple Meads

lv Bristol Temple Meads 1628 Great Western Railway

ar London Paddington 1814

The Clifton Rocks Railway was closed 85 years ago, and yet because it ran in tunnel nearly all of it still exists, and both stations can be seen (but not entered). Bristol is the site of several engineering landmarks, and a visit to the railway can be part of a very worthwhile tour. The upper station is just a block from Clifton Suspension Bridge, the most notable of the sites you should visit.

I went to Bristol twice, and I will use a few pictures from October 2018, but I only took time to go to the lower station in 2019.

It is hard to learn much about Bristol without coming across the name of Isambard Kingdom Brunel,[note 1] the innovative engineer behind construction of the Great Western Railway and the ship Great Britain, and the start of construction of the Clifton Suspension Bridge. I rode to Bristol on his railway, and there I walked across his bridge and went on his ship. And of course on this date and others I came and went through his Paddington station.

Not all of Brunel's ideas worked out. His decision to build the Great Western Railway to a gauge of 7 feet and ¼ inch wasn't wrong, exactly. The broad gauge added stability, as he hoped. The problem was that it made the Great Western and its allied railways incompatible with all the others, so for some journeys passengers had to change trains, and freight had to be unloaded and reloaded. Eventually a third rail was added to the track in places for equipment of standard gauge (4 feet 8½ inches), and finally in 1892 the last of the broad gauge tracks were converted. To illustrate the difference, below is a replica broad gauge engine at Didcot Railway Centre on mixed-gauge track. The boiler and firebox sit lower than on most engines because they fit between the drive wheels. The wooden shed is a preserved transfer station where freight was carried across between trains of different gauges.

In another misstep Brunel's Temple Meads station was built as a terminal pointed toward the city center, with a substantial stone building past the end of track, as if there would never be an extension of the railway to farther points. It was not the only case of an early railway terminal sited in this way. What surprises me about this case is that an extension was already being built, the Bristol and Exeter Railway, which would require its own separate terminal at a right angle to the GWR station. To continue on, trains from London had to back out of GWR Temple Meads and go around a bend into the BER. An platform was soon built on the connecting track, somewhat away from the station buildings. The present-day Temple Meads station was built in the 1870s with a station house in Gothic style and an impressive curved train shed connecting the two railway routes. Addition platforms were added in the 1930s in Art Deco style. There are eight tracks with platforms. Some of the long platforms have two numbers to designate the end where a train will stop. Platform 2 is not used for passenger trains, and there is no 14 (but, cheating fate, there is a 13). Two tracks without platforms pass through the middle of the 1870s station shed.

As part of the 1870s work Brunel's short train shed was more than doubled in length, and the combination was used for some terminating trains until 1965. The view below is in the extended portion, now used for a different form of transport, looking toward a wall behind which is Brunel's station, now used as an event space.

And now, the "new" station. The second picture below looks north in the the 1870s train shed. The arches on the right lead to the 1930s addition. The next picture shows the rather confined main entrance hall, ticket offices on the right hand side, a cathedral of transportation.

From Temple Meads, you can take bus 8, running every ten minutes, to Clifton Village. Clifton is about 260 feet above sea level, and you will notice the bus going up some steep hills to get there. You will not be the only one from out of town on your way to the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

I strongly recommend you take time to walk across the bridge. It's far above water level and gives some impressive views. Although it is a suspension bridge, it does not use steel rope like most, but wrought iron chain. You can see the iron bars with sockets at each end for nuts and bolts. Work on the bridge was started in 1831 but suffered a series of financial obstacles that stopped work. In 1851 iron intended for the bridge was sold and used for Brunel's Royal Albert Bridge between Devon and Cornwall. In 1860, after Brunel was dead, his Hungerford Bridge in London (1845, near the Charing Cross railway bridge) was removed and its chains were purchased for the Clifton Bridge. The bridge as built from 1862 to 1864 was a revised design with triple chains instead of double, and a stronger deck.

There is a small museum on the far side of the bridge. It doesn't open until 10, so don't get there too early. It has some good material on exhibit about the bridge. I was the first one in, when I went there in 2018, and one of the museum staff pointed out some of the hightlights to me. The bridge has a £1 toll for cars, but walking is free.

If it's a windy day with a little rain, that is a good day to visit. As I walked back to Clifton on such a day in 2018, I could feel the bridge moving a little side to side, like a large ship. I said hello to a couple my age who were coming the other way and commented on it. I pointed out that if we looked across the width of the bridge, and compared the far railing to the buildings beyond, we could see the movement very clearly. The man told me they lived in Bristol and liked to walk on the bridge, but he had not seen it moving this much. He said also that sometimes the bridge is closed in heavy winds for safety reasons. Well, it has lasted a century and a half, and the chains a quarter of a century longer, so why would it fail now? Walk on it.

There are plenty of lunch spots in Clifton Village, most of them hidden if you come by bus. A block or two in, you will find narrower streets busy with pedestrians. I stopped at the Clifton Sausage, a place that serves mainly its titular food. While I inspected the list of a dozen kinds of sausage posted in the window, my eyes turned to a table just inside the window where there was a family with two school-age agirls who looked at me, pointed at their plates, and gave smiles and thumbs up. So I had to go in. What could I do? As I left, after a plate of Old Spot sausages and mash, the family were still there, and I announced, Girls, you were right. I also glanced at the parents so they would not be concerned, as the girls laughed happily. Maybe they get lunch free each Saturday if they sit there.

It's hard to take a picture of an underground funicular railway, but the one below, as seen from the bridge, shows the location of the two stations as well as any.

I did not expect the upper station to look almost ready for business. Only when you get closer can you see that the tunnel is bricked up with a mock car end, with the correct narrow width and paint scheme. The six rails are originals, but the brick walls on each side, added after the railway closed, cover up the other two rails. There were eight rails, four tracks, for two side-by-side funiculars that operated separately.

There was once an entrance up here on the public street and another from the private road of the spa going down on the right. The platforms extend under the walk along the road, and sections of glass sidewalk supplemented light coming in from the hillside through large arched windows on the spa road. In the picture from the bridge you can see the the arched windows, to the right of my red arrow. I wonder whether one of the lifts was for the spa guests and the other for the common folk.

The railway was created to connect Clifton Grand Spa, now the Avon Gorge Hotel, with the scenic gorge. Even at the date the railway was built the lower resort area, Hotwells, was falling into decline, in contrast to the wealthier Clifton. Still the lower station offered connections to other transportation: streetcars to Bristol, a steam railway in the other direction to Avonmouth, and pleasure boats on the river. No street railways penetrated the Clifton neighborhood.

The Clifton Rocks Railway was insolvent within fifteen years, and was doomed in 1922 when the road in the gorge was widened, with the loss of the two rail connections, and increasingly unsafe access to boats because of speeding motor vehicles on the road. The railway was closed in 1934.

During the second world war parts of the tunnel were fitted out as an air raid shelter (near the top) and a secret emergency station for BBC radio, which was not let go until 1960. Meanwhile concern grew from 1956 on about the stability of the cliff face, with its retaining walls, some dating back before the railway, and the wall of the lower station itself. Buttresses were installed in 1958 at and near the lower station. They kept the cliff from collapsing, but with considerable damage to the appearance of the abandoned station.

Restoring the railway to service is considered impossible. For a two-track funicular some of the additional supports and stairways along the sides might be left in place, but the blast-proof walls and floors installed for the BBC would need to be removed. Aside from problems in the tunnel, the lower station is now in a dangerous location next to traffic. Maybe if the imaginary restored funicular ended higher up in the old station, leading to a new foot bridge over the roadway, and the Bristol ferry services came this far out... but it is still doubtful what amount of traffic it would attract.

Without a cliff railway, the only way down for me, at least the only way that is marked, is the zigzag that starts near the upper station. I knew this meant that I'd have to go back up, but it was my sworn duty to get some pictures for this page.

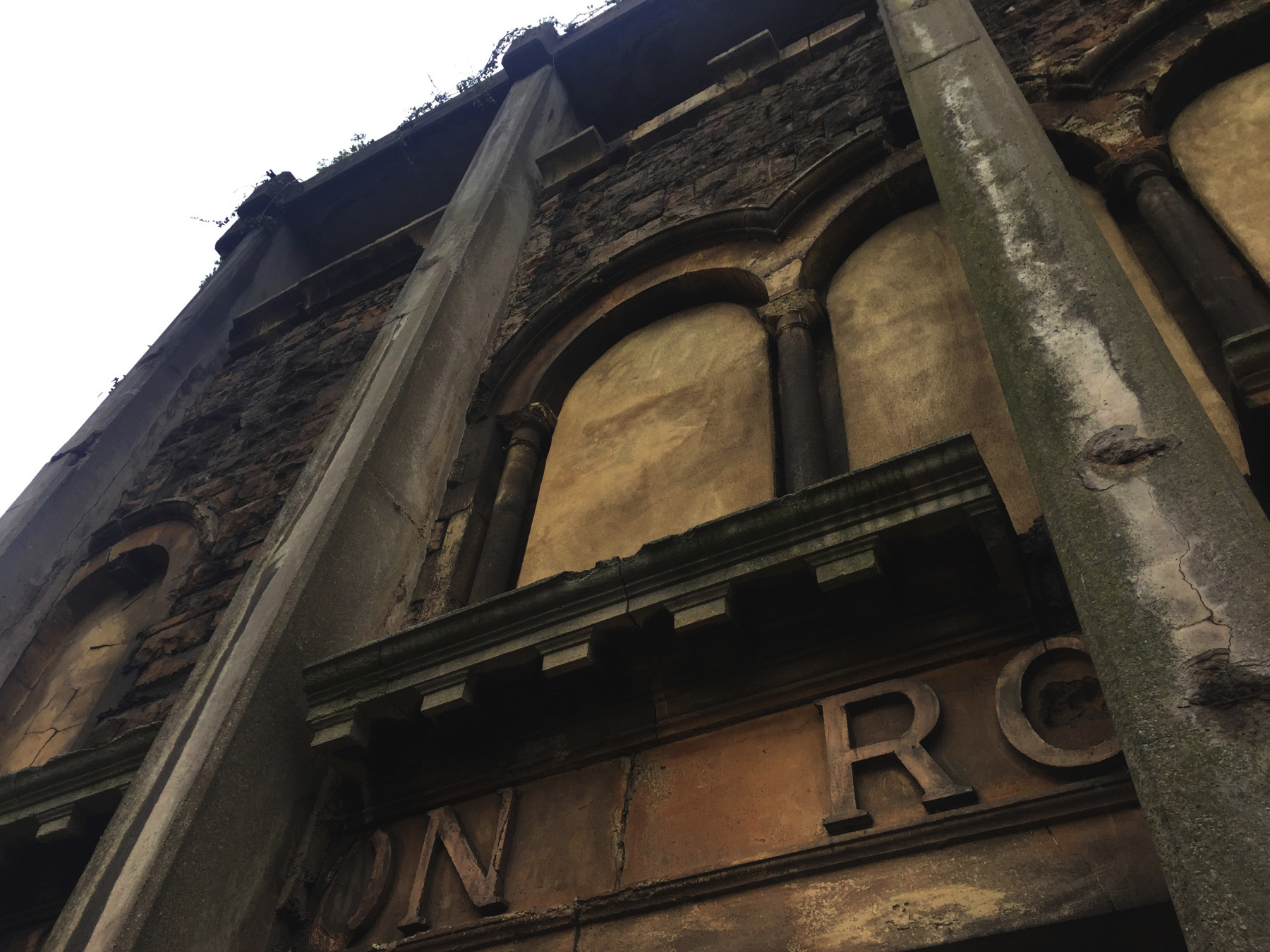

At the bottom, the walkway between the road and the cliff is narrow, so you come upon the lower station like this.

The fine cut stone arched entrance in the picture above is not for the Clifton Rocks Railway but for one of the Hot Wells, the carbonate magnesium mineral springs in the limestone cliff that first led people to come here for the waters. I could not see any water inside the barred entrance. Just beyond you can see the portico at the end of The Colonnade, a curved spa building, cut off at that point when the road was widened. The walkway right there is about one foot wide. Watch for traffic and shimmy sideways (assuming you are narrower front to back). Between these two landmarks, and not yet visible, is the lower station.

As you can see I was forced to stay close to the cliff, so while these are nice close-ups of the lower station they are not satisfactory views. You can see exactly how the buttresses were cut crudely into the old stone work. I think those rocks did not fall but were placed there for some reason I don't know. They do not protect pedestrians, who stay on the traffic side of them. Or maybe they did fall, and someone has positioned them just so at even intervals as an art installation.

So all I needed to do was find a way to cross the highway without being killed. There is no barrier to stop fools from running across, but I am not a total fool. All I needed to do was walk a third of a mile east to a footbridge, cross over, and walk a third of a mile back on the river side of the highway. That's what I did. I was on a mission.

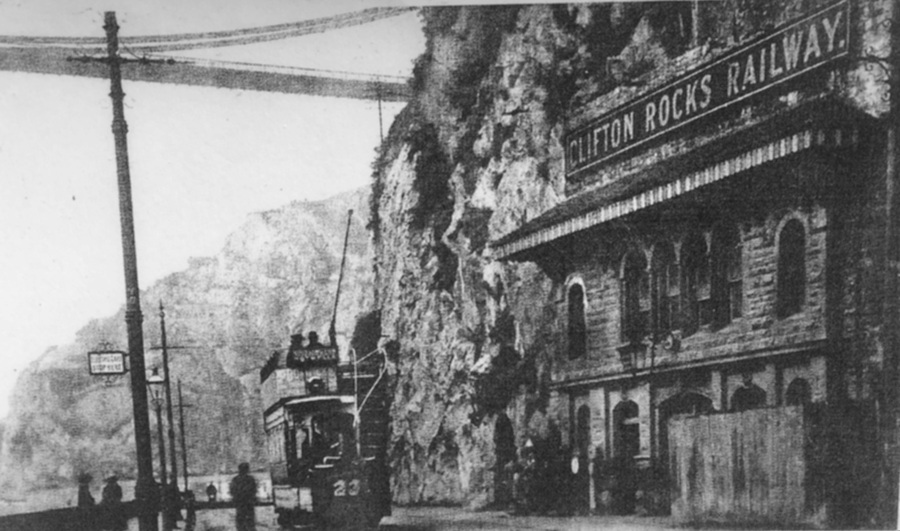

The first picture below was posted on the fence around the upper station. This is what the lower station looked like in its day. My own picture following is from almost the same point of view. The large sign on the top is gone, along with the wall surface that held it, and the supports for the awning. To replace the large sign, at some date, the arched openings at ground level were covered by flat panels with the name in relief letters (and without the "period of importance" the old sign had at the end). "Electric cars stop here" it says across the street.

My view above shows also some other retaining walls on the cliff that are not part of the railway. It looks like there is a foot path above The Colonnade. There are more patchwork attempts of cliff support hidden in the greenery.

Below, if you can take it, more sad views of the lower station. The partly hand-lettered sign on the front reads: 1891 1991 ⋮ March 7th ⋮ The Start of the Tunnel ⋮ CLIFTON ROCKS RAILWAY ⋮ opened 1893 ⋮ closed 1934. I suppose it was put there in 1991.

I didn't want to walk all the way back to that footbridge. My map showed me that if I walked west to that traffic signal in the distance (see far left, below), there was a road that went up the hill, and maybe that would get me with less distance to a bus stop. When I got to the traffic signal, not only did it let me cross unharmed, but I could see on the far side a stairway. It was the bottom of another zigzag.

Unfortunately the stairway had a sign reading "footpath closed." Fortunately at that very moment there was a man with a young boy coming down the stairs. I asked whether he had come all the way down, and he said yes, the authorities were just worried about some fallen rocks. He thought it was all right, and we agreed that neither of us had ever been struck by a fallen rock, so what were the chances. As I have said, I live for danger. If I see a rock falling I will get out of its way. I went up. I saw where rocks had fallen, but above that point I saw beautiful woodlands. The top of the path, where you come out to a street, was not marked at all, so I doubt many people expect that they can go all the way down from there. I lived to tell this tale.

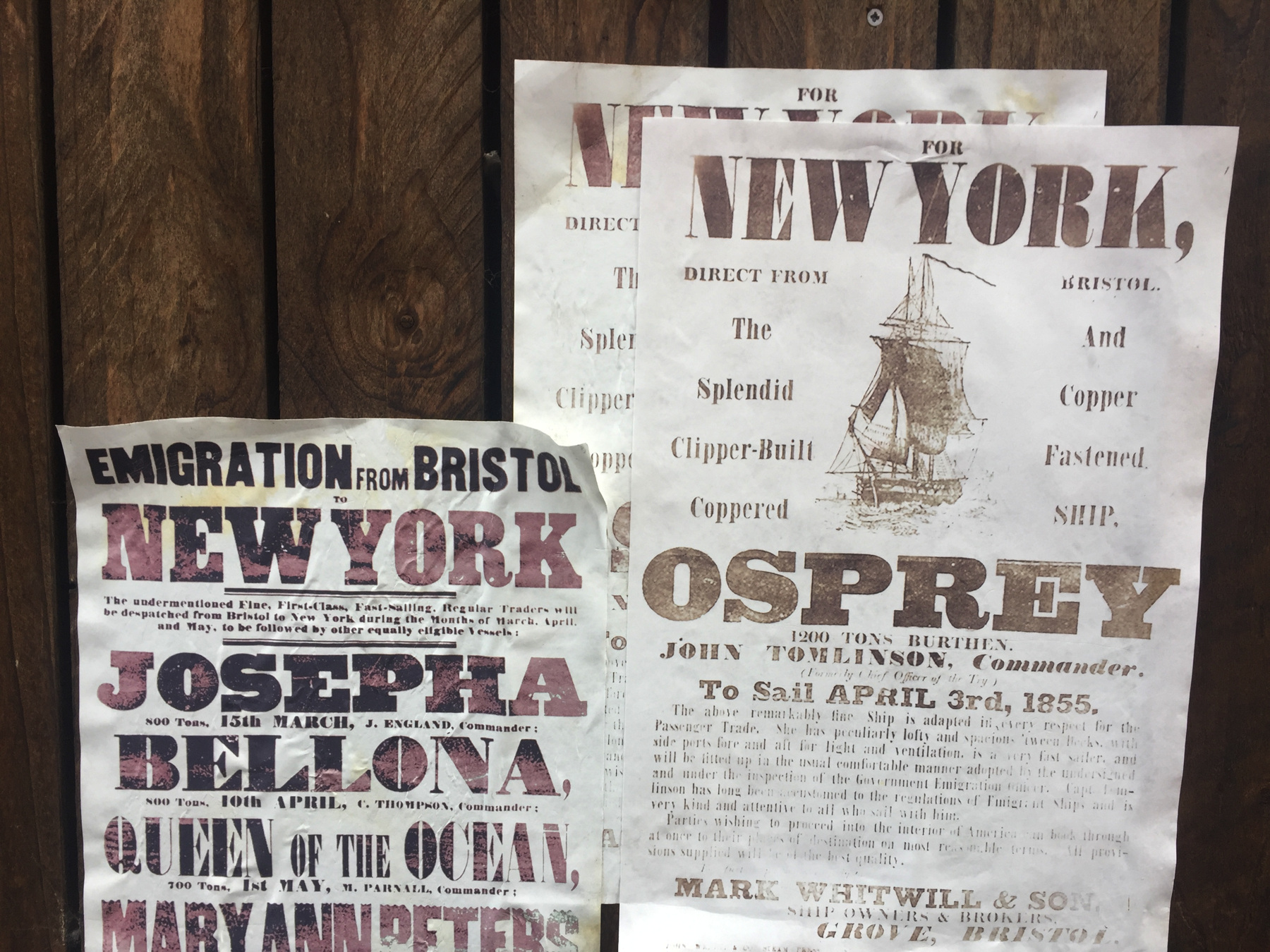

This is all I did in 2019, but if you're up for it, there could be more! I said I rode on Brunel's railway and walked over his bridge, but in 2018 I also saw his ship. The working center of Bristol is around the River Avon and the Floating Harbour, deep enough to form a protected anchorage for ocean vessels. There were once ships crossing between Bristol and New York.

Take bus 8 back down to the College Green stop and walk to Prince Street bridge. It's an interesting bridge. I know about turntable bridges, but they rotate on a center pier to open two channels for ships. This one rotates on one end.

Just over the bridge you can find the Bristol Harbour Railway, which for a small fee will give you a one-mile steam train ride along the quay to the museum of Brunel's Great Britain. The day I was there, there was some trouble with a hand-thrown switch not moving. I walked down to see. It's a volunteer operation, so I thought I would offer to help with it, but they got it to move just before I arrived. I took the first picture there. The Floating Harbour is just out of the picture to the right. The engines are kept in a building just off to the left.

I turned around and walked quickly back to the bridge to get on the train. With people all around they run the train pretty slow. That helps the passengers too since the carriages are former freight wagons without springs.

The railway's two saddle tank steam locomotives were built in Bristol and they never went farther than Avonmouth. The railway does not run every day, so check the web page. As you can see much of the space once dedicated to warehouses is now the site of modern apartments.

The Great Britain is the main attraction of the museum, but there are exhibits about the port of Bristol, and one of the buildings is dedicated to Brunel's career. In it is a section of atmospheric pipe from the South Devon Railway, but I will leave that for another time. The ship was for nine years the largest in the world, and was the first to have both an iron hull and screw propellers. It crossed the Atlantic in 1845, in fourteen days, and it later made runs to Australia. The ship was scuttled in 1937, and raised for restoration in 1970. It stands now in the same dry dock where it was built.

From the museum the best way back to Temple Meads station is the ferry. There's a stop right outside the museum. I neglected to take pictures but it's a good ride and the last stop is close to the station. The pilot house of the ferry is too tall to pass under the Prince Street Bridge, and the bridge does not open. Instead to my surprise the pilot house can move down by motor in order to get clearance. I hope that isn't a spoiler. Both times I had a good day in Bristol.

[note 1] Isambard Kingdom Brunel's unusual name comes from his father, the renowned engineer Marc Isambard Brunel, and his mother, Sophia Kingdom, but to me that is not a complete explanation.

Neither of Marc's parents carried the name Isambard, which is said to be Norman French and derived from Germanic. Sources give isn or ism as "iron" but disagree on the root of the second part, "bright" or "hard" or "brave." Given Isambard's life's work "iron" is quite appropriate, but whence his paternal grandparents Jean Charles Brunel and Marie Victoire Lefebvre took the name remains a mystery. A source says the name is more common in Normandy than in England, and "more common" can mean "less unusual".

Sophia's surname Kingdom seems to me just as odd when used as a surname. She was born at Plymouth, Devon, but her father was born in south Wales. A book published in 1851 with a short biography of Marc Brunel gives her name as Kingdon with "n", and that was the clue. Other much more modern sources find many people with the name Kingdon in south Wales, Devon, and Cornwall. It is supposed to be "king's hill" from old English cyning and dun, rather than from Welsh or Cornish. As an example of spelling variants, one source cites a marriage record from Devon in 1545 of a John Kyngdom. Sophia's father's family may be from Devon— and remarkably that was the scene of her son's plans for an atmospheric railway.

TODAY'S FUNICULAR

Clifton Rocks Railway, Bristol

Date: from 1893 to 1934

Power: Water, pumped up by gas engine

Rise: [about 180 feet]

Run: [about 400 feet]

Length: [about 440 feet]

Slope: 52%

Gauge: 3 feet 2 inches

Track: 4 tracks, straight

Car: level floor, doors at ends

From the beginning there were two narrow-gauge funicular railways running in the tunnel. The gauge is given as 3 feet, 3 feet 2, and even 3 feet 2½, and I've taken the middle value.

CLAIMS: I don't know what claims they made, but the West Hill Lift at Hastings is the only other underground funicular. Clifton Rocks is the most underground since West Hill has a little bit of open cut at each end. Clifton Rocks is also the steepest underground, and the only four-track underground, and the only water balanced underground. It's also the only one built from the start as four tracks: the other four-track funicular at Folkestone added the second pair five years after the first opened.

HEIGHT: The designer and builder George Croydon Marks gave the length as 450 in a rise of 200. While I think those are rounded off, I accept them as close to correct. (Marks also designed the Lynton and Bridgnorth funiculars, and the original two Bridgnorth cars were in the same order as the four for Clifton.) Using the Ordnance Survey maps I find a benchmark of 31 at the bottom, and another of 223 near the top, but the top is clearly below street level, so I'm calling the rise about 180. I measured the run as an even 400, not rounded off. This gives a length of 440. Both 180 and 440 are close to Marks's statement. It's all my estimates but I've done my best.

TODAY'S ALE

The Clifton Sausage, Clifton: Bath Ales, Gem Amber Ale (cask ale)