Saltburn Cliff Tramway

TODAY'S ITINERARY

Exploration: Thursday, 27 June, 2019

lv London Kings Cross 0700 London North Eastern Railway

ar Darlington 0922

lv Darlington 0940 Transpennine Express

ar Saltburn 1035

lv Saltburn Station Square 1220 [about 20 minutes late] Arriva Bus

ar Whitby Bus Station 1324 [about 30 minutes late]

lv Whitby 1600 Northern

ar Middlesbrough 1732

lv Middlesbrough 1743 Northern

ar Darlington 1811

lv Darlington 1826 London North Eastern Railway

ar London Kings Cross 2053

To reach Saltburn-by-the-Sea I took an Edinburgh express from Kings Cross up the East Coast Main Line past York to Darlington, 232 miles in 122 minutes. The name of Darlington is known in transportation history for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the first public railway to use steam locomotives, in 1825, but it was mainly for freight, and anyway it did not run through the location of this station, which dates to 1887. Below, two views of Darlington station.

There were several things to like about the local train to Saltburn.

First: It was a Pacer! As Vicki Pipe has put it, Pacers are "the Marmite of the railway world. You either love them or hate them so much you'd rather not travel at all." A Pacer is a four-wheeled diesel rail car, pretty much a bus on rail wheels, with folding bus doors and spartan seats. They run in two-car sets. They were a desperate move in the 1980s to replace ancient equipment without spending too much, in order to increase train service on branch lines. Called "nodding donkeys" or worse, they run rough on normal track and scream around curves and yet... I agree with Vicki that the open feel of the low-back seats creates more of a community feel than other British rail cars. But Pacers are on the way out and you won't find any outside museums after 2020.

Second: I have seen numerous episodes of an English detective series called Vera that is filmed in Newcastle, not too much farther north than here. The guard on the train spoke in the same cadence as Brenda Blethyn. I forget whether she called anyone "pet" or "love".

Third: We passed Redcar British Steel, the least used station in all Britain in 2017-18, with 40 passengers a year. It's no wonder. The British Steel works closed in 2015, and the station is completely within the property. There is no public road or footpath from the station. If you're silly enough to get off there, within minutes security people representing the owners will come and tell you that leaving the station will be prosecuted as trespassing. I do not know why two trains in each direction (except Sunday) are scheduled for a request stop here. All you can legally do there is get off and wait for the next train. I missed my chance to snap a picture. [Update: effective December 2019, no trains stop here.]

Fourth: We passed Teesside Airport, the fourth-least used station, with 74 passengers a year. But the count has been inflated by railway and trivia enthusiasts who buy a ticket for fun and do not travel. The true number of passengers must be much lower. The station has one train a week and I do not even mean one in each direction—I mean one, on Sunday afternoon. Teesside International Airport has not achieved the use that was hoped when it opened. That the air terminal was built about a mile from the railway station did nothing to make the railway connection attractive. As late as 2017 there was one train in each direction, but the footbridge needs replacing, and so it has been closed on safety grounds and only the platform accessible from an airport road can be used. I did grab a shot of this one. You can see hangars in the distance.

I think in both cases the stations are being kept open (barely) both to avoid the costly procedure of officially closing a station and to keep the site on the books for future use. When the large British Steel property is sold for some commercial or residential development then a station at or near the site will be desirable. In the case of the airport it's not obvious to me what the future will hold.

Below is a portrait of our Pacer at Saltburn station. Below that is an interior view of a different Pacer of the same class, showing the bus seats, and the pass-through to the other car of the pair. Each car has one door on each side. (The second picture is "Refreshed interior of First Great Western Class 142" by Peter Skuce, 2008, public domain, from Wikipedia Commons.)

The only "welcome to station name" sign I could find at Saltburn was stored off to one side. That's unusual. The street side exterior is in great condition but it says "railway station" instead of the name of the station. It's the end of the line, so if you're on the train you can't miss your stop, and if you're outside the station you probably know what town you're in.

It was a great day to be on a cliff top over the North Sea. The short walk from the station gave me fine views to the south and before long at all, there was the cliff lift.

The upper station is barely larger than the car, but it is a well-kept jewel of Victorian style. It was early in the day, so, no waiting. Let's go down to the pier. (Sorry for the focus on the last one.)

You'll notice that the pier head building is in the same style as the upper station, and the lower station is too, although you can't see it from this side.

I walked out on the pier.

Here is the lower station and a couple of views of the cars going up and down.

And... that was it. I'm done here. And it's just noon.

I like the Saltburn Cliff Railway. It's a small one in a small town, nothing like the commercial stimulation and crowds of Scarborough or Bournemouth. It's the cliff and the sea, with just enough added in the form of a cliff lift, a pier, and a few shops. You can relax here. It was quiet. I'm glad I came.

This one is water balanced, using water from a spring somewhere near the top, but unlike the river source at Lynton there is not a generous steady supply of water here, and so the water is stored in a large tank at the bottom and pumped back up to a smaller tank at the top as needed.

When I was planning my days I thought it wouldn't take much time to experience this funicular, and I considered whether to combine it with Scarborough. The only transportation along the coast is by bus. It's an hour from Saltburn to the Whitby bus station and a second hour on a second bus to Scarborough. The days were long in June, but the opening times of the funiculars not so much, and losing more than two hours on a bus in the middle of the day was not practical.

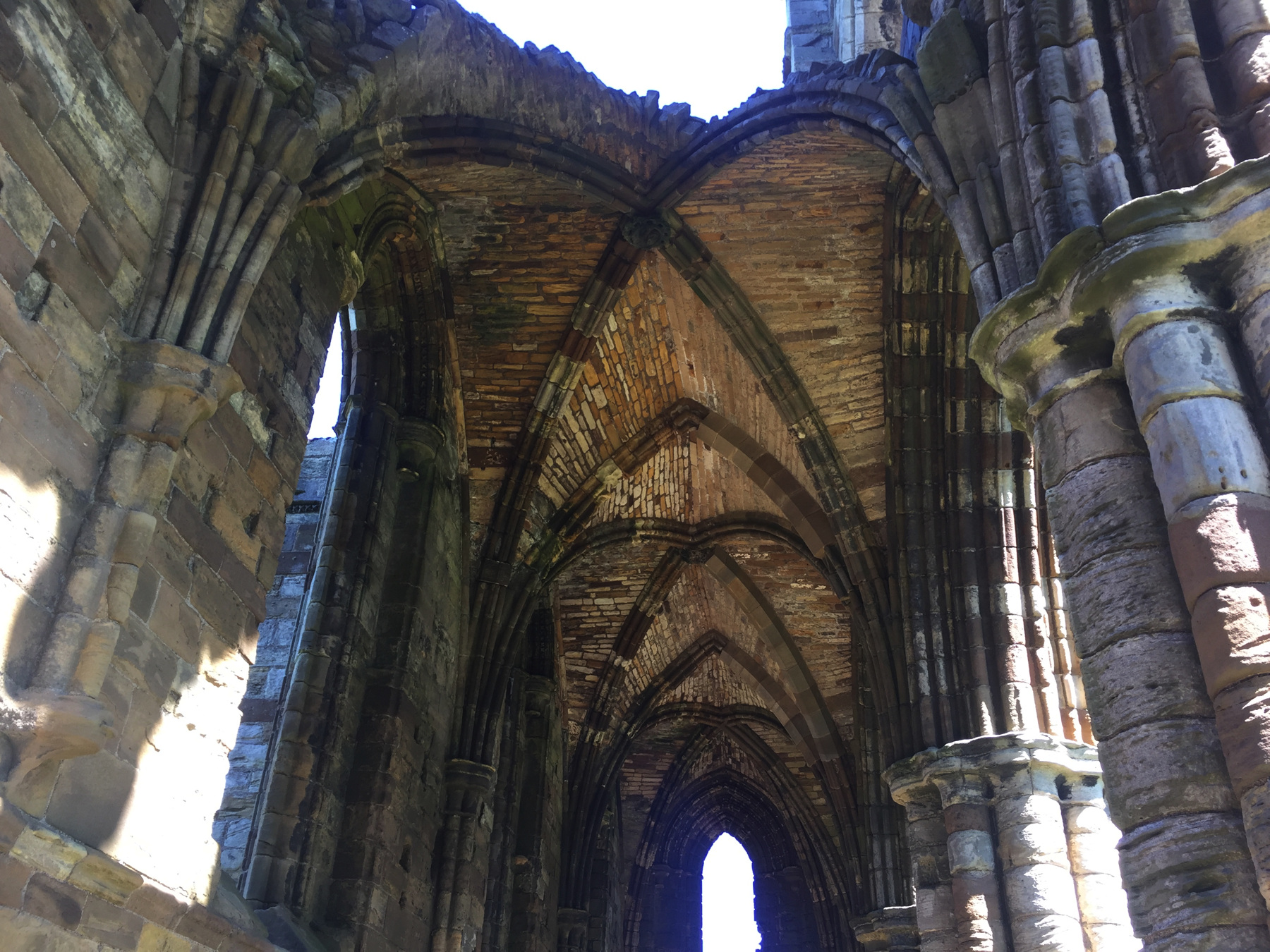

But... Whitby? Now that is something. It's not easy to reach from London but it's not so hard if you set out from Saltburn-by-the-Sea. Whitby is where Dracula's ship landed.[note 1] And there's huge ruin of an abbey built a thousand years ago and abandoned five hundred years ago. And there is a little personal factor: when we lived in Manhattan, my daughter attended pre-school and first grade at the school of Saint Hilda and Saint Hugh, and there is in its exterior brick wall a couple of bricks missing to fit a stone from the abbey of Saint Hilda at Whitby. I wanted to see the abbey.

Saltburn station, seen from the bus stop.

Whitby station, seen from the bus stop. You can just about see the ruins of the abbey up there on the hill.

The bus at Saltburn showed up 20 minutes late, and we lost more time at a stop where a passenger in a wheelchair was taken off to go into an automobile repair shop and then return some minutes later, no doubt having satisfied a bodily function we all have—the patience of the bus driver being an act of human kindness to which I could not possibly object. The route of the bus detours off the main road here and there in search of passengers. It goes up and down hills, alongside the cliff top over the sea, and inland past fields and small villages. It was a wonderful ride.

To reach the abbey, you go up the 199 Steps. Cute name. I was going to count them to blow the lid off this tourist trap. And then I noticed that every tenth riser has a small white marker on it with the number of the step, in Roman numerals yet, X ... XX ... XXX... XL ... It gets to CXC but the last one, nine steps further is not numbered. There is no step CC. It really is 199 steps.

Above, the view from the Church of Saint Mary, built from the twelfth to nineteenth centuries. Bram Stoker wrote in Dracula, "For a moment or two I could see nothing, as the shadow of a cloud obscured St. Mary's Church. Then as the cloud passed I could see the ruins of the Abbey coming into view..."

And here it is.

The abbey is an English Heritage site. If you get there, pay the entrance fee, because it goes to a good cause, and experience it. The only thing is, this is not the abbey of Saint Hilda. That was destroyed in the ninth century, and this is the replacement. The stone at my daughter's school looks different. I wonder where it came from.

There is railway service at Whitby, and not only that, there is railway service by two companies. Northern runs four trains a day in each direction, limited by the 35 miles of single track on the Esk Valley line to Middlesbrough and the sixteen intermediate station stops. It takes 90 minutes each way. The steam locomotive heritage line North Yorkshire Moors Railway also runs on the same track as far as Grosmont, where it branches off.

I took the Esk Valley train. A short distance out of Whitby it passes under the high viaduct of the one-time railway from Saltburn to Scarborough. It then runs for many miles in the valley of the Esk, through woods and past small village stations. About halfway to Middlesbrough the passing scene starts to open up into fields with views of distant hills. There's a place at the edge of a field where the train has to change ends because this surviving route was patched together from two railways that met here at a trailing junction.

And... the train was a Pacer! Two seats ahead of me and on the other side were three old men, and I could half hear that they were discussing stations, old buildings nearby, and the like, the good stuff. I wondered how far they'd come, but then two stood up and said good-bye and left at one of the tiny stations, and the third got off two stations later. Because it was a Pacer I had felt drawn into their discussion.

The length of the journey did not bother me. This was such beautiful country. As the Scenic Rail Britain web site site puts it, "Whatever the weather, the scenery along the Esk Valley line is spectacular, from bleak moorland to sheltered, woody glades along the River Esk." I'm not sure I saw anything bleak. Maybe that pointy hill there. This is the source of that sheep photo. I'm going to omit it here, if that's all right.

I changed trains at Middlesbrough. It is pronounced as if the missing "o" was there, middlesburrow. I am just amazed at the nineteenth century details at some of these local stations. I expect elaborate work in cities where the railway company wanted to impress, but they could not stop there. Look at the columns on the platform, which the present-day railway company takes the trouble to paint appropriately. And how about the medieval church detail inside the station house! Despite the pink banner, I swear I took these pictures in June 2019.

[note 1] An excerpt from Dracula by Bram Stoker, with a description of Whitby that I can appreciate so much more after being there, even if it was for less than three hours. Coming up from London, Mina Murray's train probably arrived at Whitby Town, the station in the valley of the Esk where I took a train from Whitby. It would have run on the more direct route from York, namely the present branch to Malton, the now-lifted section to Pickering, and the present-day North Yorkshire Moors route.

MINA MURRAY'S JOURNAL

24 July. Whitby.—Lucy met me at the station, looking sweeter and lovelier than ever, and we drove up to the house at the Crescent in which they have rooms. This is a lovely place. The little river, the Esk, runs through a deep valley, which broadens out as it comes near the harbour. A great viaduct runs across, with high piers, through which the view seems somehow further away than it really is. The valley is beautifully green, and it is so steep that when you are on the high land on either side you look right across it, unless you are near enough to see down. The houses of the old town—the side away from us—are all red-roofed, and seem piled up one over the other anyhow, like the pictures we see of Nuremberg.

Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey, which was sacked by the Danes, and which is the scene of "Marmion," where the girl was built up in the wall. It is a most noble ruin, of immense size, and full of beautiful and romantic bits; there is a legend that a white lady is seen in one of the windows. Between it and the town there is another church, the parish one, round which is a big graveyard, all full of tombstones. This is to my mind the nicest spot in Whitby, for it lies right over the town, and has a full view of the harbour and all up the bay to where the headland called Kettleness stretches out into the sea. It descends so steeply over the harbour that part of the bank has fallen away, and some of the graves have been destroyed. In one place part of the stonework of the graves stretches out over the sandy pathway far below. There are walks, with seats beside them, through the churchyard; and people go and sit there all day long looking at the beautiful view and enjoying the breeze. I shall come and sit here very often myself and work. Indeed, I am writing now, with my book on my knee, and listening to the talk of three old men who are sitting beside me. They seem to do nothing all day but sit up here and talk.

The harbour lies below me, with, on the far side, one long granite wall stretching out into the sea, with a curve outwards at the end of it, in the middle of which is a lighthouse. A heavy sea-wall runs along outside of it. On the near side, the sea-wall makes an elbow crooked inversely, and its end too has a lighthouse. Between the two piers there is a narrow opening into the harbour, which then suddenly widens.

It is nice at high water; but when the tide is out it shoals away to nothing, and there is merely the stream of the Esk, running between banks of sand, with rocks here and there. Outside the harbour on this side there rises for about half a mile a great reef, the sharp edge of which runs straight out from behind the south lighthouse. At the end of it is a buoy with a bell, which swings in bad weather, and sends in a mournful sound on the wind. They have a legend here that when a ship is lost bells are heard out at sea. I must ask the old man about this; he is coming this way....

He is a funny old man. He must be awfully old, for his face is all gnarled and twisted like the bark of a tree. He tells me that he is nearly a hundred, and that he was a sailor in the Greenland fishing fleet when Waterloo was fought. He is, I am afraid, a very sceptical person, for when I asked him about the bells at sea and the White Lady at the abbey he said very brusquely:—

I wouldn't fash masel' about them, miss. Them things be all wore out. Mind, I don't say they never was, but I do say that they wasn't in my time. They be all well for comers and trippers, an' the like, but not for a nice young lady like you. Them feet-folks from York and Leeds that be always eatin' cured herrin's an' drinkin' tea and lookin' out to buy cheap jet would creed aught. I wonder masel' who'd be botherin' tellin' lies to them—even the newspapers, which is full of fool-talk."

That's right. Those city people would believe anything. For example take what happens within a fortnight: a ship drifting in, with no sign of the crew but the body of the captain tied to the mast and clutching a crucifix, tied there by his own hands, and the great dog that jumped from the ship when the tide changed. What fool talk does that inspire? Nonsense of course.

There are today tourist shops in Whitby selling jet. Some things don't change.